As the results began pouring in to decide who would occupy the office that Americans like to style “leader of the free world,” my country collectively held its breath (except, presumably, those prognosticators who had assigned Hillary a greater than 99% chance of victory; they must have had better things to do than follow the actual results). By the end of the evening, they had all believed they had witnessed the most stunning upset of modern political history. But had they?

I should think not. To begin with, there are two ways to think about a politician doing better in a race than is expected. The first is as the candidate winning an upset, but the second is as the polls having a miss, and this latter interpretation is much closer to reality. Trump did not especially overperform, but actually received fewer votes than any Republican as far back as George W. Bush’s first run in 2000, which is especially pitiful considering that the pool of eligible voters grew by twenty million over the intervening span.

Rather, Trump’s victory came decidedly from Hillary Clinton’s weaknesses, which evidently were not sufficiently understood prior to the election. Perhaps some of the blame for this nearly nationwide myopia can be assigned to the prevailing model of political punditry, which seeks to explain polls with electoral factors, rather than using electoral factors to predict results. In other words, even many of our savviest talking heads tried to explain what was shaping the race by starting with the conclusion that Clinton was winning by several points, and working backwards from there to try and figure out why. Investigations into the minds of voters, the trends on the ground, and the actual issues at stake in the race all took second billing to running horse-race backup. Is it any wonder that they got it so wrong?

Having been disabused (rather suddenly and rudely) of the notion that Clinton had a secure lead, we can now more easily see the factors that led to the race being so competitive. They are not so mysterious; major warning signs presaged them and were ignored, including by myself personally.

One of the most obvious warning signs was Clinton’s ability to blow huge leads in Clinton in both the 2008 and 2016 Democratic primaries. Both times, she lost due to a lack of personal magnetism and an inability to capture the “change” vote. Perhaps we forgot at some point this cycle, but all one needs to do to realize the charisma gap between her and the last two winning Democrats, Obama and Bill Clinton, is watches clips of their speeches side by side. And Clinton’s being closely tied to the political establishment in the primaries presaged how many would feel about her in the general. Ironically, all her greatest strengths–mass support from politicians, financiers, and the media–merely served to emphasize that losing attribute.

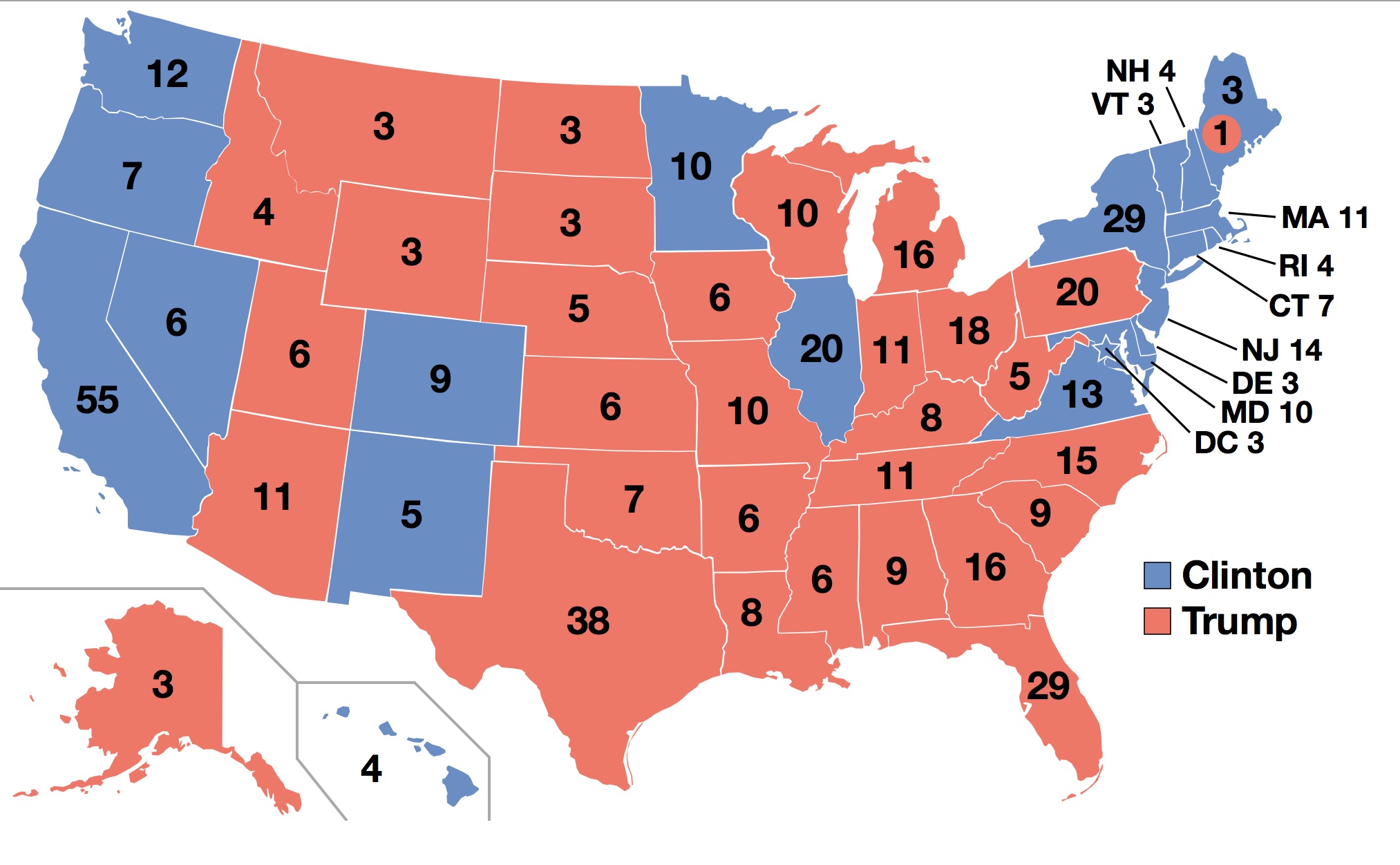

Another warning sign was the shifts that white, less educated midwestern states had already undergone. Obama won Wisconsin in a landslide in 2008, but his margin fell by about 7 points in 2012, and Clinton’s margin fell by almost exactly the same amount four years later, handing Trump a narrow lead in the state. The same trajectory of improving Republican margins can be mapped out, if not quite as accurately, in Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. In the lower-turnout midterm elections of 2010 and 2014, Republicans won 16 of 21 of the senatorial and gubernatorial races in those states, an impressive three-quarters.

So the question could have been framed as, “will 2016 have turnout that’s higher or lower than usual?” The sheer negativity of the race helped settle that. With both candidates less popular than any since polling began, two-party turnout dropped dramatically, to 51%. It had been 57% in 2012 and 59% in 2008. With low turnout, Trump carried all of the previously mentioned 6, except Minnesota, where he lost narrowly.

The final warning sign was the enthusiasm gap in the Democratic and Republican primaries. Democratic turnout fell by a third from 2008, the last year there was a competitive primary. Republican turnout increased by half. In a bruising, dirty election with depressed turnout, it should have been clear that Republicans would be likely to stick around to vote at a higher rate.

But these are trends, not absolutes, and one would be mistaken to read them that way. At best, someone reading these trends properly should have deemed the race merely competitive, a toss-up. Predicting a Trump victory would have required getting the final tallies almost exactly right.

For Trump’s victory was incredibly slight. His “tipping point” state that won him the presidency was Pennsylvania, which he carried by only a 1.24% margin. In other words, had just two thirds of one percent of voters switched from Trump to Clinton nationally, she would have won, and all the analysis about what this election says about America would have been different. The winner-take-all nature of the presidency, then, really creates a false binary: only Trump advances to take office, but America remains cleaved very nearly in two, when it comes to the ballot box. There is likely truth–but not absolute truth–to many of the various claims and counterclaims: racial resentments drove buoyed Trump, as did economic grievance, and anger at liberal condescension. The Democratic claim to the progressive majority majority of the future also seems supported by Hillary’s slight popular vote victory, as well as improved showings in states like Arizona, Georgia, and Texas. There is no reason why these cannot all be true to a significant degree, each driving their own share of the final tally.

America, after all, contains multitudes, and though the Republican Party will start 2017 controlling the country more thoroughly than any party has in decades, it would do well to remember that.