My first thought is that the O2 Academy is a boring venue for a band with a sound as warm and story as unique as Tinariwen. These men are guitar legends of the Sahara and former members of Muammar al-Gadaffi’s guerrilla training camps. They are, as NPR have dubbed them, “music’s true rebels”. An O2 Academy is the opposite of rebellious.

This room is usually stifling hot. Tonight, a seriously strong air-conditioning blast suddenly hits halfway through Tinariwen’s set. My friend suggests it’s the desert wind. Next, he says, there’ll be a sand storm.

For Tinariwen (itself a Tamasheq word meaning ‘deserts’) are very much at home in the sand dunes of the Sahara. These musicians grew up as part of the Tuareg rebel community, in nomad camps in the far north-east of Mali, and later in refugee camps in Algeria. Witness to rebel movements and violent attacks, the band was formed as a collective in the late 1970s. Founding member Ibrahim Ag Alhabib first made his own guitar with a tin can, a stick and bicycle brake wire. Now Tinariwen count Thom Yorke, Chris Martin and Brian Eno among their fans and have seven studio albums and a 2012 Grammy tucked under their belts.

The music they play has even been named ‘desert music’, but that doesn’t bear the brunt of it. Tinariwen are influenced by Algerian pop rai, classical Egyptian pop, and Moroccan protest songs, alongside western pop and rock artists, folk and the blues. During the early days of the collective’s existence, Tinariwen’s members got their hands on bootlegged copies of western albums including Led Zeppelin and Jimi Hendrix. It’s not hard to see how music became their driving force for a political resistance.

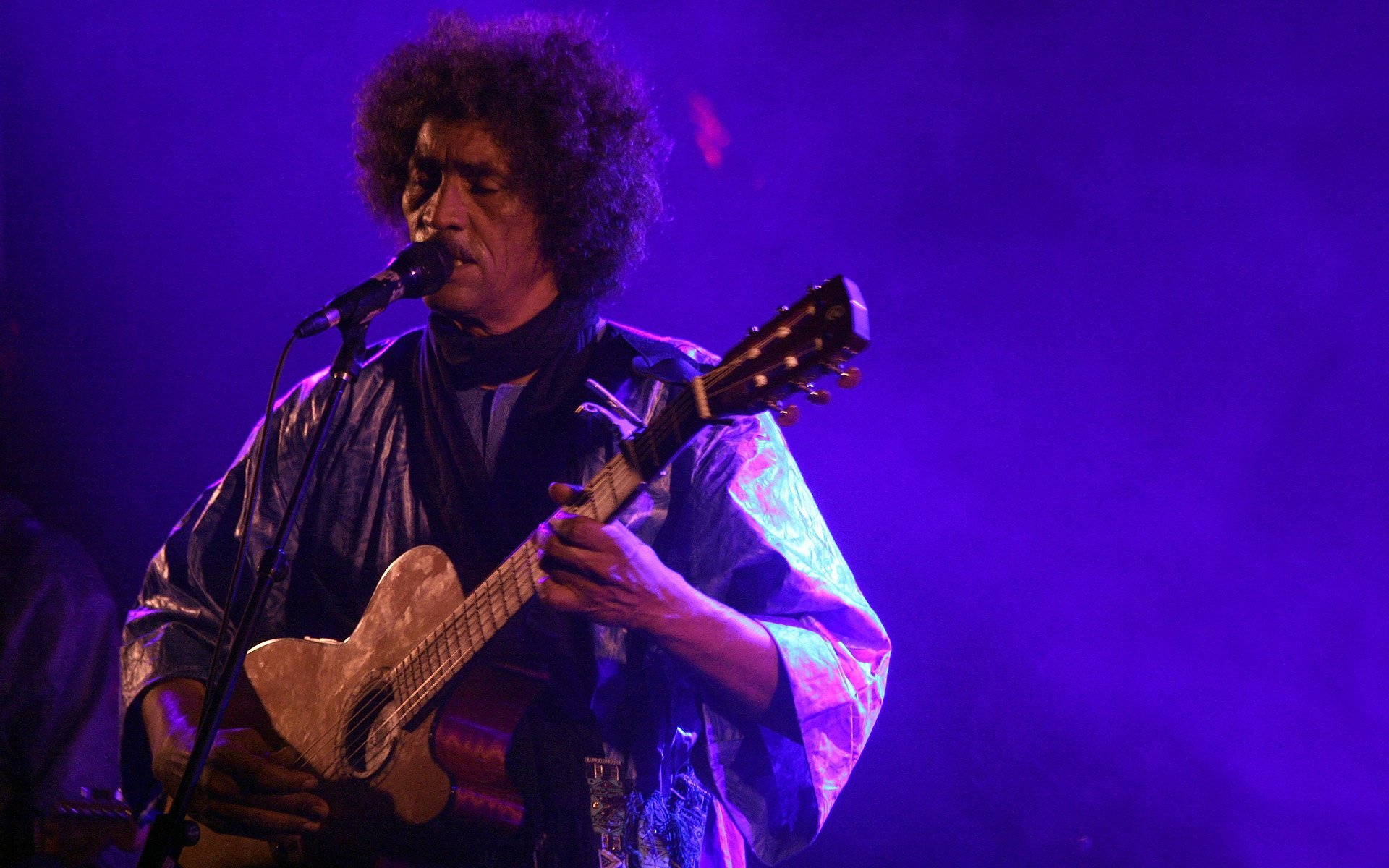

This insistence on music as their saviour is evident onstage. Tinariwen sing in their native Tamasheq language about ongoing troubles in Mali, a changing homeland and the beauty of the desert, and they wear traditional flowing robes and turban-veils. They dance with an otherworldly passion for what they are playing, their insistence on its danceable capabilities as encouraging as the audience who cheers back at them.

There is no need to translate Tinariwen’s incessant rhythmic groove. Layered guitar riffs take centre stage, the intricacy in the finger-picking marking these players out as seriously talented musicians. This guitar shredding works best when strung along at odds with the vocal lines, as the band’s call and response vocals resound in gloriously sustained harmony. There is a wonderful complexity to the texture, too, when the tindé drum is played at odds with Eyadou Ag Leche’s limber, and undeniably funky, bass, as it kicks along on tracks such as ‘Imdiwanin ahi Tifhamam’.

The set ends in ‘Chaghaybou’, from the 2013 album Emmaar, a perfect example of the rhythmic restlessness with which Tinariwen play. The track’s final lyrical image is of Chaghaybou, the song’s addressee, being taught the Tifinagh alphabet by his mother in the sand. “In the sand”—the crucial environmental detail wholeheartedly missing from this gig which is otherwise so full of the sincerity, graciousness and musical finesse Tinariwen take with them no matter how far from the Sahara they wander.