Who was the greatest Western artist of the twentieth century? It’s an unfashionable question now, as it has been for nearly five decades. Academics shun such arbitrary ranking and consider more objective questions, rather than indulging in subjective grading. It’s peculiarly hard for the twentieth century too; it might not be unreasonable to proclaim Michelangelo as the greatest of the sixteenth century, but how do we go about comparing Freud with Pollock with Warhol? It’s futile.

Nonetheless, it seems clear that if you were to name the three most important artists (which is not quite the same as greatest) then academics and critics might agree upon Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, and Henri Matisse. Significantly, all had made their artistic breakthroughs before the end of the Great War, allowing for their influence to percolate through the rest of the century and into ours. They also all worked in Paris, moved in similar circles, exhibited in the same exhibitions, and the three were inspired by the example of Cézanne: to break away from the rigid confines of painting only ‘what you could see’, exposing the fictions of academic art.

Yet from the vantage point of a hundred years on, of this trio, Matisse emerges as the finest, most formally coherent and consistent. If Picasso tailed off in quality after Guernica (1937) and Duchamp became consumed by chess in the nineteen-twenties, never to fully re-engage with art, Matisse stands alone: from his early Fauvist paintings, like the scandalous Woman with a Hat (1905) to the startling, laconic cut-outs of the nineteen-forties, his output was prodigious and luminous.

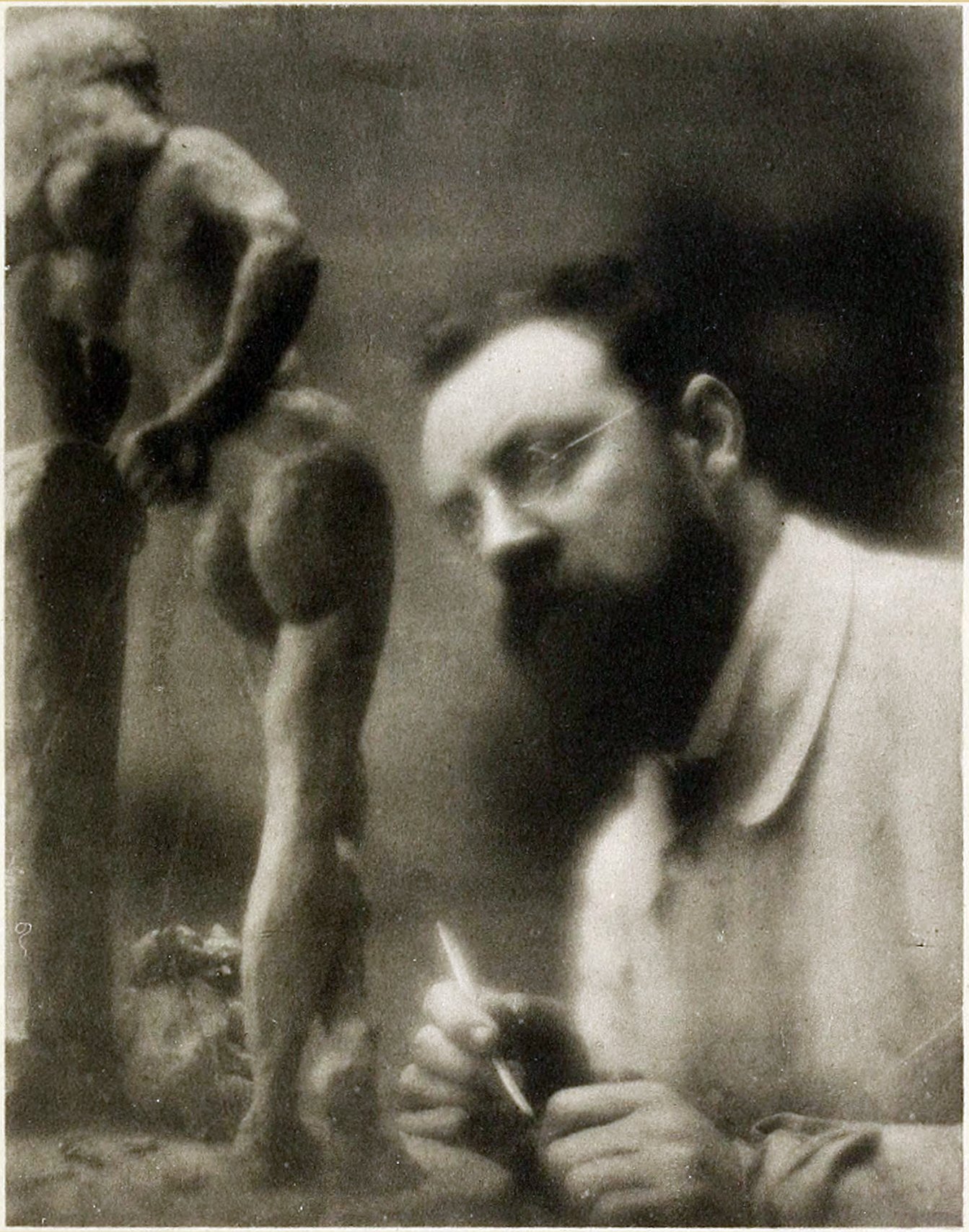

That’s what makes the new Matisse exhibition at the Royal Academy such a joy. There is little attempt to establish a biographical continuity, or to explain how he continued to exhibit in Vichy Nice during the Second World War. They are questions for another show. What is important is the art and Matisse’s practice of it. As the exhibition title hints, Matisse in the Studio wants to show how his art often sprung from the objects around him, taking inspiration from a diverse set of cultures.

Early on, the curators highlight a marvellous quote from Matisse, taken from a letter he wrote to Surrealist poet Louis Aragon in 1942:

‘I have at last found the object for which I’ve been longing for a whole year. It’s a Venetian baroque chair, silver gilt with tinted varnish like a piece of enamel. You’ve probably seen something like it. When I found it in an antique shop, a few weeks ago I was bowled over. It’s splendid. I’m obsessed with it.’

Here, before the viewers, is the selfsame item, a battered, faded nineteenth-century chair, with a pair of sea serpents’ heads where the arms curve down to the seat. There are a row of paintings and charcoal drawings behind it, showing Matisse’s shifting representations of it, using it as a prop in his still lifes. In one, Rocaille Chair (1946), he represents the chair from a high vantage point, as if we are looking down on it, the arms now sea-green and deploying a flat brass gold for the rest, while the background is a dark matte maroon, folding the background and foreground into one. Not only does this painting emphasise Matisse’s glorious facility with colour (equalled only by Pierre Bonnard), but it points to Matisse’s own guiding artistic ethic: ‘For me, the subject of a picture and its background have the same value… there is no principal feature, only the pattern is important.’ Just as relentlessly formalist as the Cubist Picasso, and sharing many of the same sources of influences in African art, he departs from the orthodoxy of Modernism by his embrace of ornament and pattern, both in colour and line.

This becomes apparent in the most successful gallery of the exhibition, ‘The Studio as Theatre’. The antiseptic white walls of the Royal Academy’s Sackler Wing are antithetical to trying to summon the spirit of an artist’s studiolo, and the placing of Chinese porcelain, totemic figures from Gabon, and French chocolate pots besides their painted representations are not wholly successful. Yet in the penultimate gallery, covering Matisse’s Middle Eastern fantasias, an extraordinary series of women posing as odalisques, surrounded by rich, polychrome tiles and North African textiles, the show comes together. Matisse had visited Algeria in 1906 and spent consecutive winters in 1912 and 1913 in Morocco, collecting furniture and objets d’art, learning the deep lessons of Islamic art.

The gallery creates a set Matisse may have recognised (the fittings are all his): a large, nineteenth-century screen on the back wall, a small, eight-sided ornate painted table known as a guéridon from Algeria, and a Moroccan chair. Buttressing the artefacts are the paintings themselves, including The Moorish Screen (1921), a stunning work of two women in a domestic interior wearing Western clothes but in Arabian surroundings. The palette is astonishing, the line work delicate, his deft handling of the painting’s innerspace and swathes of patterned paint almost comparable to wallpaper. But it is glorious wallpaper, of the type you have never seen before and you will never see again.

It is a relief, after such orgiastic beauty, to leave the gallery and see the cool, clarity of Matisse’s cut-outs, their bold shapes and blocks of colour a reduction in form which cleanses the palette after the complexity of the previous visual effects. It prepares us to return to a duller, greyer world, for we cannot see our world with Henri Matisse’s eyes, and that is our tragedy. Whatever the curatorial weaknesses may be, this exhibition is essential in the sense that great beauty is essential to all our lives and we need to be able to revel in it. Go.

Matisse in the Studio is on at the Royal Academy until 12th November, 2017.