As the complicated divorce that is Brexit continues, I have begun to look at the marriages it has disturbed. My own family was arguably made possible because of Britain’s membership of the European Union. Though my father’s parents were Italian immigrants, he was brought up in Britain. Back in the ‘90s, after finishing his degree, he decided to move to his parent’s holiday home in Italy to improve his knowledge of the language. With a little bit of pidgin Italian that sounded more like French, and armed with a British music collection that outshone much of what one could find in Italy at the time, my father managed to woo my Italian mother. A few years into their relationship, after I was born, my parents decided it was best to bring me up in the UK, given the dubious economic future for Italy with the corrupt media tycoon Silvio Berlusconi taking its helm once again in 2001. Despite initially being horrified at the apparently overwhelming mass of velour tracksuit-clad teens in the UK (my Mum is a fashion designer, and so cares quite a lot about clothes) and missing Aperol Spritzes and olives before dinner, and her job in the fashion capital of Milan, my mother settled in very well. She learnt English quickly, so much so that she appears to whatsapp my British friends more than I do myself.

Since then, our family has expanded to include three more children. At least once a year, thanks to budget airlines and the EU, we go back to Italy to visit our family there, and the way we all behave somehow re-adapts itself to an Italian climate. I often return from Italy, making hand gestures as I speak, pronouncing the occasional ‘No’ more like the abrupt ‘Nó’ and struggling to maintain a Mediterranean diet. Inconvenient as it is, I think this is the beauty of being in a family that has a culture that is ultimately ‘Europeanised’. Yes, I would rather not drink a cappuccino in the late afternoon, but no way would I ever dance to Reggaeton (which I despise) with the same enthusiasm as Italian people tend to. There are many families in Britain like my own made possible by virtue of our European Community. But since Brexit, there will be fewer and fewer. I spoke to two mothers from Oxford, my own, Monia, and her friend Agnieszka, about how they feel as EU nationals who started a family with a British partner, after it was decided that Britain was to leave the European Union.

***

I asked Monia how she felt after the result of the referendum. She explained that she was pretty shocked as was everyone else, but more shocked by the floods of messages she was receiving from British colleagues and my British friends apologising for the result, and worrying about what was going to happen to her. “It felt like all of a sudden, I had to wear the ‘immigrant’ badge, one that I never felt I had to wear before.”.

We talk about betrayal. How does it feel to work hard to integrate oneself in a foreign country and then be rejected from it? Agnieszka remarks how she “felt unhappy with the referendum. Yes I think voting Brexit was in a way racist, but I don’t personally feel betrayed. I think those who are betrayed are those who weren’t informed well when they voted to leave.”. Monia nods in agreement, “I don’t feel betrayed because nationality isn’t important to me. I don’t feel like an immigrant and I have never suffered from racism in England. I actually come from a very racist country so when I first came here I thought it was such a beautiful place to live […] especially London because of its multicultural nature. But I did happen to pass by an EDL rally once in a small town. They made me feel really uncomfortable, and that’s when sometimes I feel like people don’t want me here.”.

Yet did they not feel they had a right to vote in the referendum? Agnieszka is a public sector employee and works as a teaching assistant at a local primary school, yet had no right in a decision that could compromise the future of her job. Monia had no right to vote in a referendum in a country where she has lived and paid tax for almost twenty years and yet still receives postal voting slips for Italian elections and referenda. They agree that as UK taxpayers, this is a more valid reason to be able to vote on a decision of direct relevance to them than simply being born somewhere where you might not even live anymore. Monia thinks it is ridiculous that the Italian consulate sends her postal voting slips when she feels she has no right to make those decisions because she lives here. On the other hand, she argues that she had a right, as a mother of British children and a UK taxpayer, to make a choice over Brexit, and that right was denied.

We discuss the characterisation of immigrants from the EU in Britain. The school where Agnieszka works used to be my own primary school, and is currently attended by my siblings and her children. I recall my friends who went there complaining a few years ago about how ‘Polish’ it had become and gawping about how the Polish headmistress at the time occasionally spoke Polish to Polish pupils. A part of Agnieszka’s role is to assist children of Polish origin whose parents might not be so familiar with the English language with their literacy skills. She doesn’t understand why there is so much aversion to the Polish community within the school when they are trying to integrate, and many of them encourage studiousness in their children. Monia added that a lot of the children from the primary school who managed to get into a grammar school were of Polish origin, which in her views challenges the argument that schools go downhill when they have an increasing proportion of Eastern European students. Agnieszka suggests that the ‘Polonisation’ of the school is exaggerated. The school is a Catholic primary, and being from a very Catholic country, many Polish parents would prefer to send their children to a faith school, thus explaining the ‘high’ number of pupils. People forget that before Polish immigrants arrived, Catholic schools were hardly ever dominated by English pupils, but were largely filled with pupils of Irish, Italian and Iberian descent.

Both Monia and Agnieszka have settled in Britain reasonably well, yet what about other EU nationals who are finding it more difficult to integrate? Monia admits that she has not received poor treatment as an immigrant, but admits that she was an immigrant with a degree and from a highly professional background. For others who leave their country to come here it is much more difficult. Monia talks about the children of some of her Italian friends who have recently migrated to the UK for work, given the high youth and graduate unemployment rate in Italy. She stresses that they are not ‘stealing’ jobs, they are just doing whatever jobs they can get. These jobs are low pay and are usually unwanted jobs such as in care for the elderly or in busy restaurants; often with dubious contracts or none at all. “These people live in much worse situations than a lot of those who voted to make them leave! Where does all this envy come from?”. They both note how they are lucky as EU nationals who have children with British nationals. They will not be made to leave, but others will not have the same luxury, even when they have only just taken the big step of leaving their own country behind, only to be asked to turn back again.

***

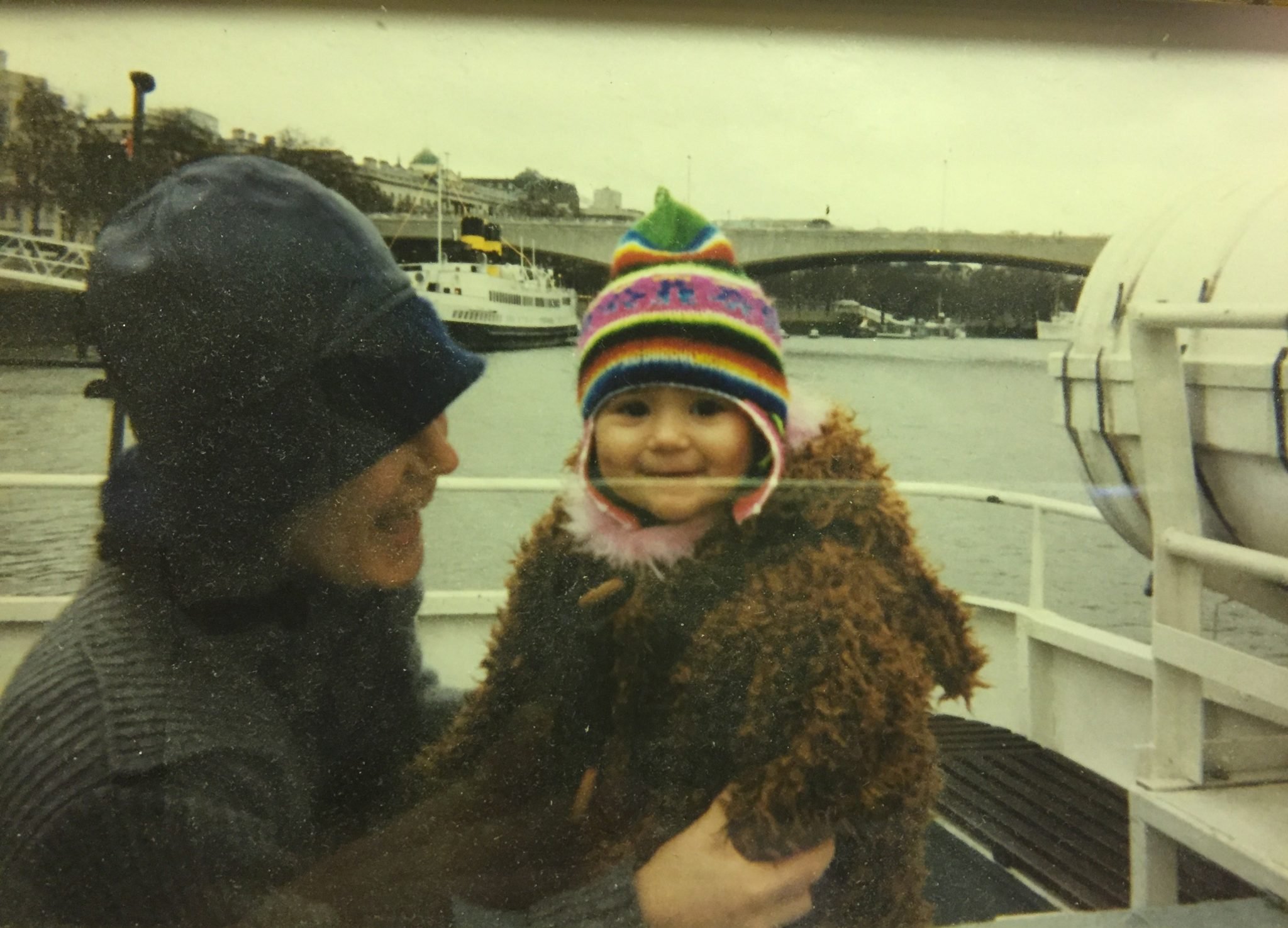

I remember speaking to my mother the day after the referendum, when she joked that she was going to have to pack a suitcase to go back to Italy. My twin brothers who were five at the time locked her in their arms between them, chanting, “We won’t let Mummy go back to Italy!”.

I asked her what she would say to those who voted to leave the EU, expecting a fervent gush of anger. But instead she replied calmly, “It doesn’t matter what happens to me anymore. What matters is what will happen to you. I hope they will help us pick up the pieces for your generation because of the mess they have made. They’ve created uncertainty and that is completely wrong.”. She looks down at my brothers’ glossy heads and caresses them lovingly, “You should not put children into this world to throw them into the sea- you should give them a stable environment, one that stretches beyond the borders of this country.”

***

What Agnieszka and Monias’ experiences reveal is that there is no ‘them’ and ‘us’. The only divisions between EU citizens living in Britain and British people exist in the newspaper headlines. This country may be divorcing itself from the EU, but it cannot break the human relationships made possible by the European project.