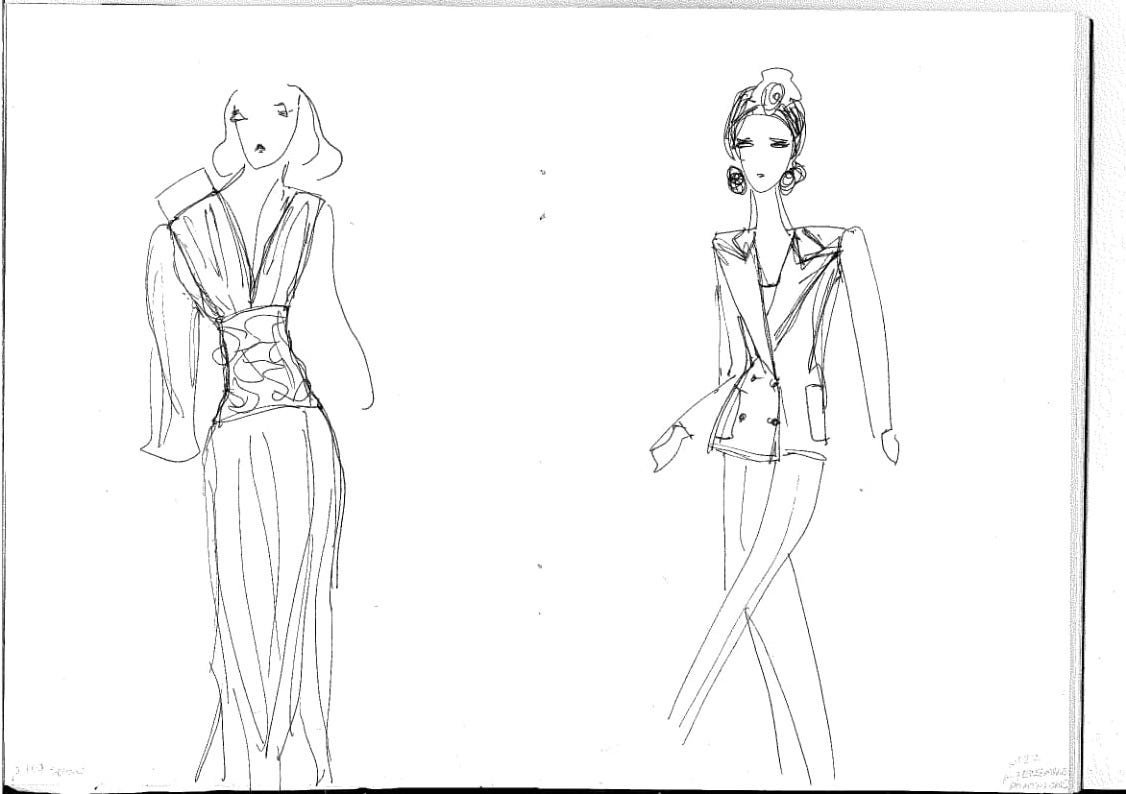

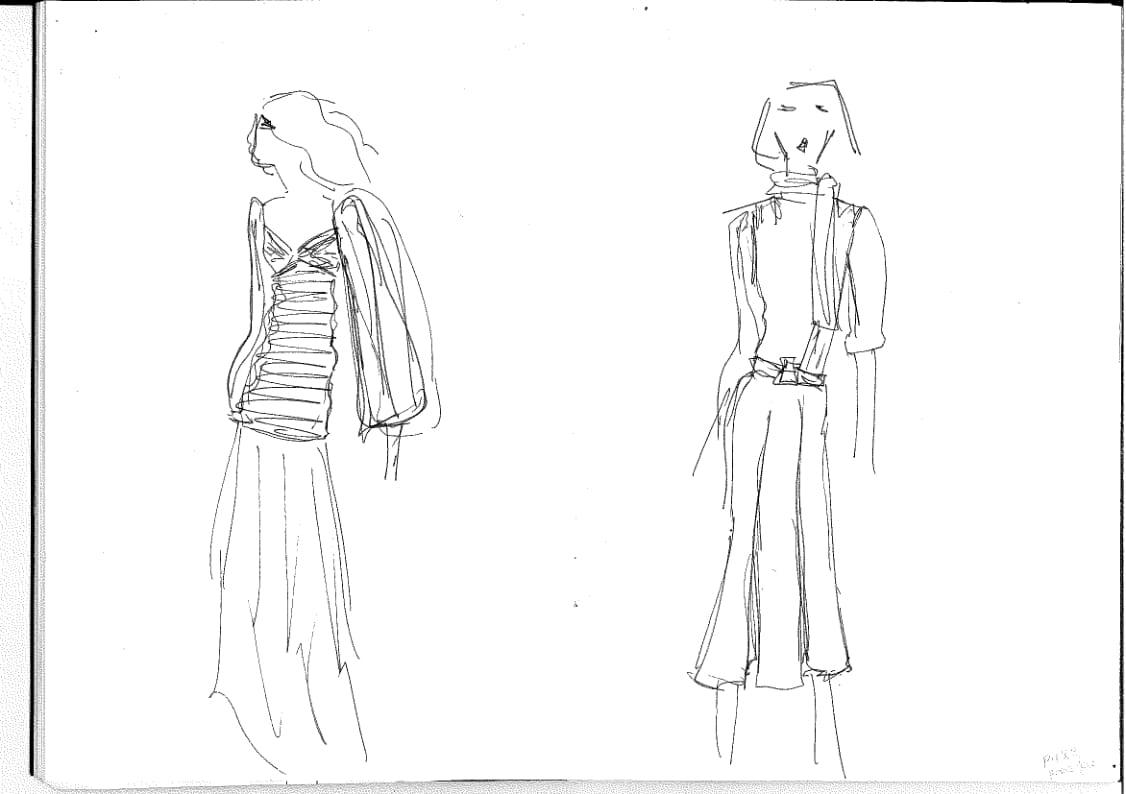

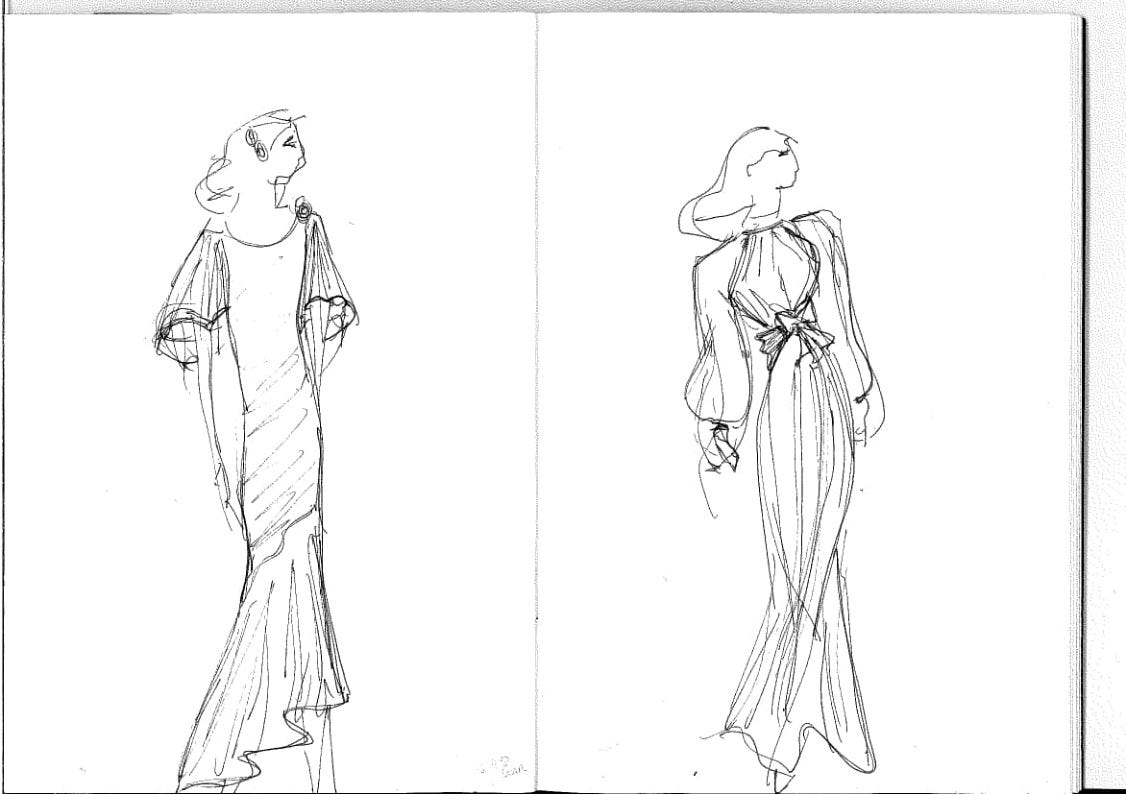

The 1971 Yves Saint Laurent Collection du Scandale highlights the instant, ever-changing nature of fashion as well as the day-to-day freedom it bestows. The scandalous collection – at the time a commercial failure – sparked outrage for displaying what have now become high-street staples of today – black flares, blocky strapped heels, chunky fur jackets, and waist-glorifying silhouettes.

Retro looks are the bread and butter of the contemporary fashion moment, but Saint Laurent, who asks the question “What can we really call ‘new’ in fashion?” was heavily criticised for the resuscitation of feminine 1940s styles in his ’71 collection.

This collection is but one of many portals into the greater cultural debates that exist within fashion. Fashion does not exist in a vacuum, it is made up of rules and temporal references whether you choose to break, follow, or twist them – you can only manoeuvre within this network of visual symbols.

Momentarily fleeing the constraints of academia, I see fashion as an escape – yet this is perhaps ironic as history often shows us that fashion is also something to escape from. Virginia Krause writes about the social codification of clothing in Renaissance France, where women were reified whilst men reaped social prestige from the sartorial adornment of their wives and daughters. Having an expensively dressed wife was a status symbol for a man, proving his wealth and status capable of supporting female dependants. Women’s idleness was scorned, and ‘idle’ women who did not have to work could dedicate themselves to a personal grooming regimen that was commodified and appropriated by men.

Though things have changed a lot since then, the “highly codified language of prestige inherent in how one dressed” identified by Krause reverberates with some aspects of our own society [Krause, 2003. P. 105]. She observes that the 16th century French poet Louise Labé understood that lavish clothing procures only the illusion of personal honour while in reality reinforcing male hegemony, which perhaps bears an echo of the ‘self-care’ trend of our own time; I’m certainly not the first person to draw attention to the fact that painting your nails is perhaps not the purest embodiment of self-care. According to Krause, Labé believes that “women can aspire to loftier ambitions for their leisure than self-adornment” which generates symbolic capital for men [Krause, p. 107]. Whether men or women are the target audience of an outfit, a conversation in Sex and the City between Carrie and Charlotte about the former’s new heels highlights the calculated communication potential of garments in our own time:

[Carrie]: Do you think they make the right statement?

[Charlotte]: Well what statement do you want them to make?

[Carrie]: I am beautiful and powerful and I don’t care that you’re only 25 and married my ex.

[Charlotte]: I thought you didn’t have a complex about how you look to other women?

[Carrie]: Oh no, it’s not a complex, it’s a Natasha-specific obsession, which will be over as soon as she sees me, at the benefit looking fabulous in these shoes, and this dress I saw at Bergdorf’s that’s gonna cost me a month’s rent.

The literature of Early Modern France depicts a world where everyone is hyper-aware of codified outward appearances, and on many levels it doesn’t seem so different from today. Nothing stands alone in fashion: it is fundamentally a form of communication with a receiver, a viewer, a target. Perhaps this is part of why fashion-blogger Leandra Medine’s philosophy of “man repelling” through clothes took such a hold. It completely subverts the Renaissance French system, taking female ownership over fashion as a form of expression and focussing on, in her own words, “trends that women love and men hate”. These ideas are fortified in her book – Man Repeller: Seeking Love, Finding Overalls. Yet the notion of man-repelling suggests that this form of dressing still functions in a male-focused system, only this time dictated by what men don’t like.

Is it really possible to dress entirely for yourself? Is fashion a codifying device that traps women in a system of visual reification? It is virtually impossible to dress completely neutrally; every choice makes some form of statement and an outfit speaks a thousand words.

Maybe fashion is at once freeing and constraining. But this tension may be exactly what makes it exciting and unsettling: this visual world of constant flux somehow manages to be both a refuge from the real world and something to seek refuge from.