Here are some things that some people have said about Elvis:

“I wasn’t just a fan, I was his brother.” —James Brown

“It was like he came along and whispered some dream in everybody’s ear, and somehow we all dreamed it.” —Bruce Springsteen

Did they really know Elvis? Funnily enough, they might have done. I wonder, though, whether in their own fame, and after having actually met him, they would still say they feel the same. As the man himself said:

“The image is one thing and the human being is another. It’s very hard to live up to an image, put it that way.” ― Elvis Presley

There’s a fundamental difference between the way that people perceive the man, and the way the man perceives the people. This is not a reciprocal relationship—it’s one-way. We can see that there’s an illusion of connection: this is the driving force behind the phenomenon of celebrity. Only now, celebrity has met with the technology that allows it to reach its full commercial and social potential.

The reason we’re so

interested in celebrity is quite simple: we aren’t one.

They illuminate the central conflict of experience: though we know we are

insignificant in the grand scheme of things (sorry for the reminder), we have

no way of observing the world in a way which reflects that fact. We only know

the world in first person; the ‘subjective centrality’ of our lives is in

direct opposition with our objective insignificance. Celebrities are a way of

managing this troubling truth, because the illusion of connection makes us feel

we know them intimately as no other does—but, in the back of our minds, we know

that everybody thinks this.

The figure of the celebrity shapes, on the one hand, the social consciousness: it is both a product of and producer of the society of which it is a part. That is to say, it is born of the media and, once born, sustains that very same media by the content it produces as it vies for relevance. Though I’m sceptical of blindly following Marshall McLuhan’s dictum ‘the medium is the message’ (well, yes, but come on, people do say things, don’t they? There’s content in what they say?), I think in this case it might hold. The very existence of an article about a celebrity demonstrates their presence – and that we should talk about them. McLuhan exemplifies this through the idea of a public opinion poll, which both gauges what that opinion is, but also proves that there is a public opinion in the first place. A magazine article does the same thing for celebrity.

The celebrity also sustains the individual, with what, in some cases, may be false nourishment. People absorbing media —believing in both the idea of media and in what it says— is what sustains it. A young girl might think: “if that video says this about Miley Cyrus, it must be true, and I ought to copy her because everyone likes her—otherwise the video wouldn’t have been made— and that’ll help me to fit in with everyone else”. She would then keep absorbing media in order to get more information, and the cycle continues because the media outlet will fabricate content which matches the image of the star to keep selling. As she absorbs it, she changes her behaviour: in this way celebrity becomes a yardstick, an ‘other’ around which to construct ourselves.

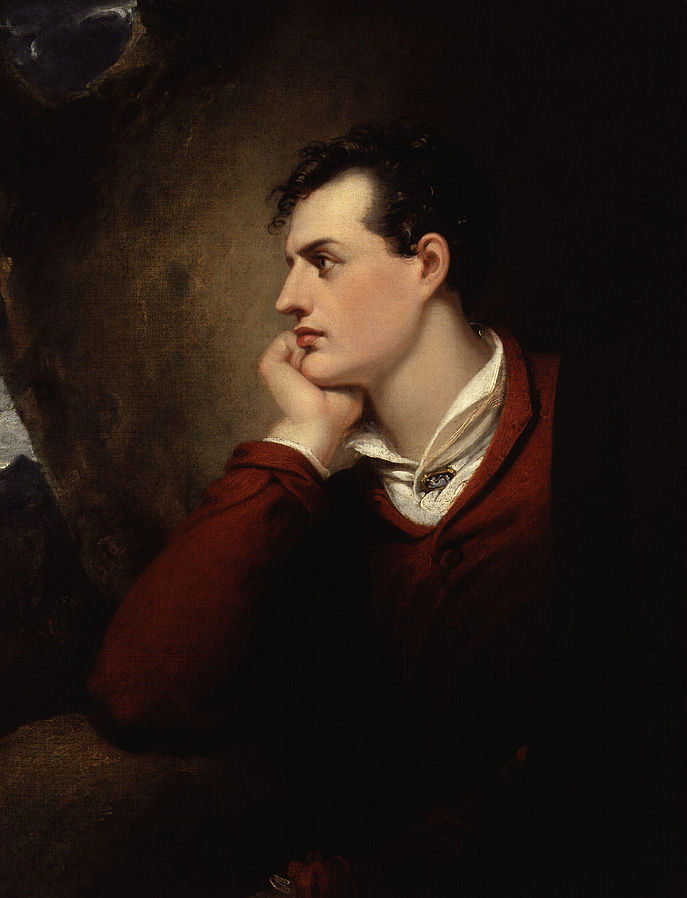

There used to be a subtle depth to celebrity: take Byron, for instance, or Liszt—essentially the rockstars of their ages, known from afar. People talked about them; they speculated, word of mouth and rumour accumulated with the force of avalanches, and their legends spread. But the modes of reproduction couldn’t circulate masses of information about them; media was limited in time, space, and, through censors, even in content. Thus, it was always a one-way connection, which allowed no mistake: you couldn’t really imagine Byron was talking back to you or played any role in your life. He was merely a symbol. He may as well have been fictional.

Technology developed, and these mediated representations of a person drew closer and closer to what looked like reality—but was actually a rather a meagre construction of it. The illusion of connectivity grew and where there is a feeling of emotional investment, so come the Omnipotent Forces of Moneys to profit from that emotion. America, predictably, led the way in this, and Hollywood became a factory of images.

Now we come back to Elvis. If we note, though, the past tense, the sort of wistful tone of Brown and Springsteen, we see that they’re reliving what they used to think. Any magic that used to hang over Elvis like a halo has dissipated to some extent, because at this point, they too are famous.

They were once like us. (I say ‘us’ assuming you’re not famous.) When they become like Elvis, the intoxicating thing about him—the strange oscillation between his distance and his closeness to them—loses its power. The twentieth century, a time of exploding advancement, of television, of broadcasting, was a breeding ground for feelings of closeness with people who existed worlds away. So frequent and intense did intrusions of media into daily life become that, I would argue, an illusion of ‘two-way’ connection emerged. This connection needs to be illusory; if you actually become friends with a celebrity, and develop a real two-way connection, then you become interested in them in a completely different way.

The illusion of two-way connection creates a real sense of inspiration which shapes the way we think about ourselves. Psychologists call it ‘motivation by association.’ “If this man Elvis can do it, then so can I.” Of course, everybody else had the same access to him. The more media outlets, though, and the more there was a more regular sense of his face and voice being seen and heard everywhere, the greater was the feeling that one was ‘plugged-in’ to a direct line to Elvis—and wouldn’t we all just love one of those.

Celebrities became symbols of themselves—plus something else, something powerful. The frameworks of mediated representation—the four sides of the TV and the billboard, the bandwidths of the radio—infused their personality with an extra mystique. The difference between Marilyn Monroe and Byron was that Monroe was that much more in the public eye. Paradoxically, the more she is presented, the more she becomes flat: the more the public feels they know everything about her.

Here we reach the present day —yes, I’m going to talk about ‘influencers.’ Their goal is to create the ultimate ‘two-way’ connection, something that was previously impossible. They can literally interact with fans. The product is now synonymous with the advertisement, because, as mentioned, a celebrity is both a product of and a reproducer of a commercial society. The celebrity can now directly sell their personality to brands.

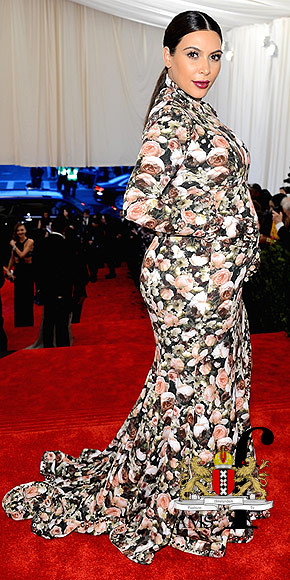

With respect to the ‘flatness’ and ‘depth’ which I’ve mentioned, I’d say that the modern celebrity now appears to be completely flat, which is where their new interest and marketability comes from. If we take the Kardashians, who are nothing if not ‘known for their knownness’—having very little to actually make them famous (well)—we feel we completely understand them. I’m not saying that there isn’t more to them than what Keeping Up with the Kardashians and Instagram present, but the illusion which reality television casts is one of a perfect facsimile of the Kardashians’ lives. The show requires us to believe that we’re seeing everything, even though that may not be the case.

Unlike in Byron’s time, the media is no longer restricted by platform or by time and space. Social media eliminates those limitations. Internet influencers are closer to us than any stranger has ever been. Imagining that we’re able to see everything in the Kardashians’ lives makes us aware of their similarity to us, but also highlights their differences. We like watching (bear with me even if you don’t) because we see distant lives of glitz and glamour; but then, we also know they are only people, because we’ve watched their children grow up. They are similar, therefore relatable; but their otherness also makes us feel we are more, counters our insignificance, because we define ourselves against them: “I’m more than that. I’ve got more nuance than that.”

The Kardashians and the internet celebrities have weaponised personality. They harness the potential of the media to beam a commercialised, cultivated image of themselves straight into our everyday lives; it is all the more powerful because we actively choose to follow them. And we choose to follow them because other people follow them; it is only the technology that has changed. They are free to perform relatability; brands love it because it automatically inserts their product into the everyday life of an audience.

So, things have changed. Celebrities used to be used to be symbols. Now they rely on seeming completely and utterly themselves, on creating the illusion (is it an illusion?) of a two-way relationship. This, if it is nothing else, is the most powerful commercial model yet. How long will it last? Will they always seem so authentic? Or perhaps they’re more like Alexander McQueen’s piece depicting Kate Moss, from his 2006 ‘Widows of Culloden’ show in Paris—a hologram, strangely close and ever, ever distant.