The Royal Academy’s current exhibition, Lucian Freud: The Self-portraits, is a bold and singular response to this century’s fascination with self-image. Lucian Freud’s artistic career predates the selfie-saturated 2010s, yet his work captures the obsession and volume with which we display ourselves today. As Nancy Durrant says, ‘it is the perfect show for an egomaniac’. By piecing together Freud’s self-portraits through the years, we witness a rare and striking event: the lifetime pursuit of an eye intent on viewing itself.

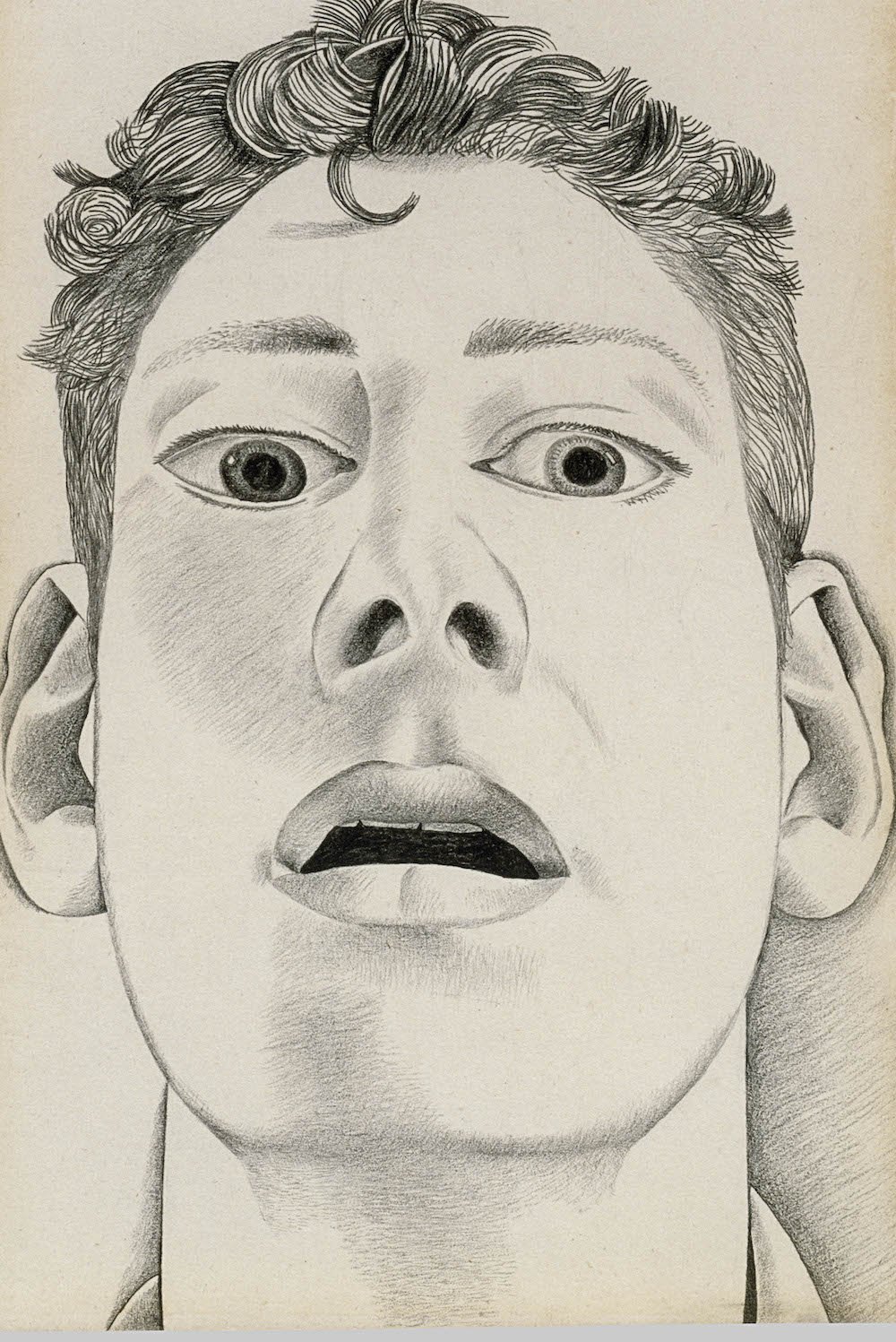

With a portfolio spanning nearly seven decades, the Royal Academy displays Freud’s work broadly chronologically. The exhibition begins with his teenage sketches, including the ‘Self-Portrait as Acteon’ (1949) – one of four drawings where Freud is drawn as a mythological stag. Turn around, and you see ‘Man with a Thistle’ (1946) and ‘Man with Hyacinth’ (1948), where Freud is composed alongside his plants. He attempts something of narrative in these earlier studies. There is the anxiety of how best to present oneself – one which endures throughout his life. As Freud admits, in a statement that might resonate with us all:

“I don’t accept the information that I get when I look at myself and that’s where the trouble starts.”

Freud felt early that he could never quite represent himself – that his style needed to develop as he did. He writes in his only published piece, ‘Some Thoughts on Painting’ (1954),

“A moment of complete happiness never occurs in the creation of a work of art. The promise of it is felt in the act of creation but disappears towards the completion of the work… It is this great insufficiency that drives [the artist] on.”

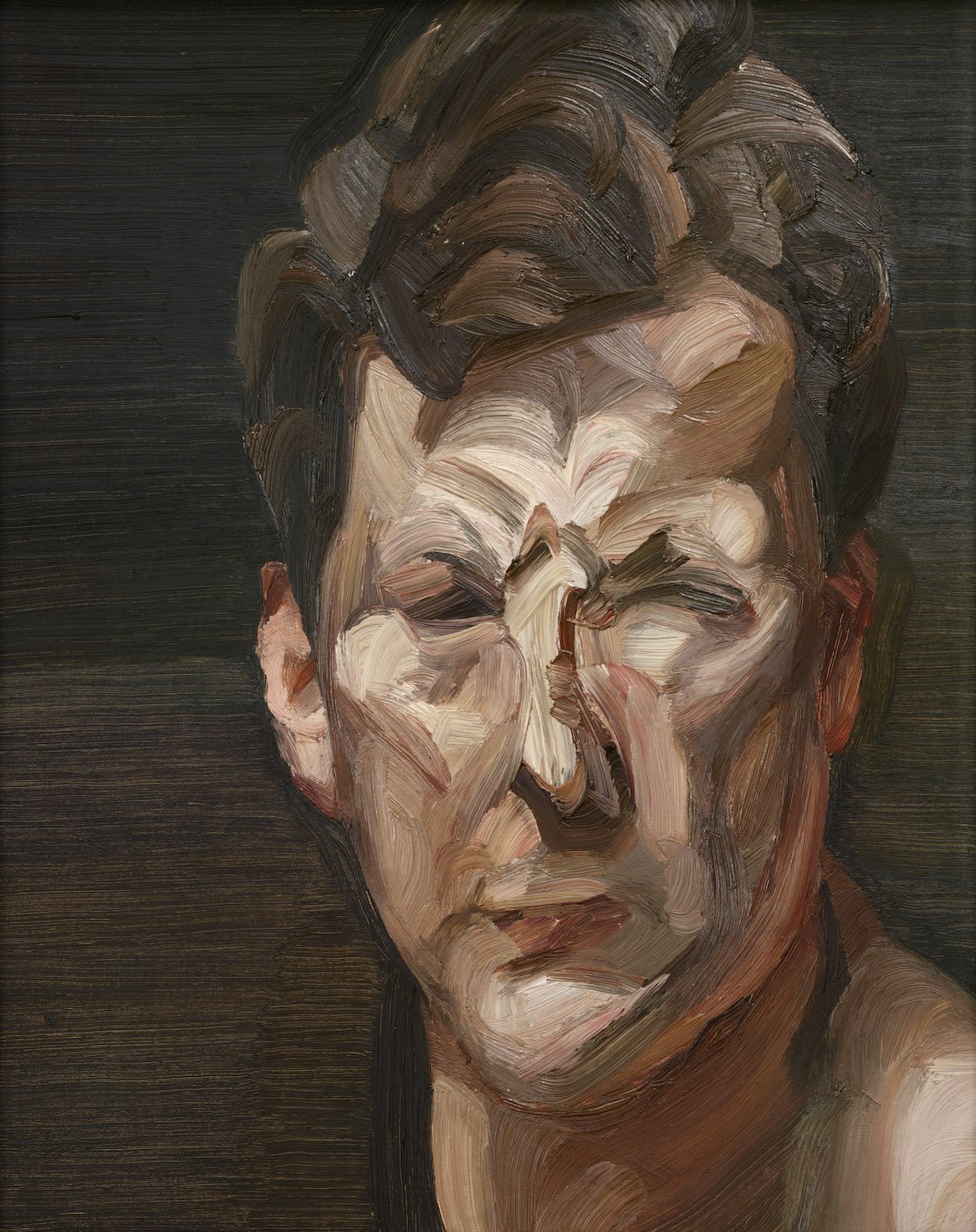

This drive is clear throughout. As the exhibition continues, Freud visibly moves away from geometric frames towards looser compositions. In terms of tools, he switches to coarser hog’s hair brushes upon the advice of his close friend, Francis Bacon. Gone are the companions of flower, fruit, or feather; the subject alone remains. The same questions persist: who am I, why this moment, this angle?

His ‘Man’s Head’ series (1963) is three self-portraits painted in rapid succession. The triptych interrogates both physical and psychological structure as emotional immediacy takes priority. Freud measures his own face against his quickly developing mood and style; the challenging expressions are aimed at him as much as us.

In the same space, a smaller study, ‘Self-portrait with a Black Eye’ (1978) fights for attention. Freud’s forehead swells inside the frame; his skin bulges yellow and purple and the uncomfortable crop offers no relief. Freud is his own unbearable subject: he paints with a constant fascination and dissatisfaction with what he sees. The portrait’s magnification is arguably key to his process. In the ‘Thoughts’ he suggests that:

“The painter’s obsession with his subject is all that he needs to drive him to work.”

This ‘obsession’ extended beyond Freud himself – into his other portraits and commissions – yet we always find glimpses of him in whatever – and whoever – he sees. Even as he paints others, there is a clue of brush in a mirror, the sight of a hand at work, or in the case of ‘Flora with Blue Toe Nails’ (2000), a shadow looming on a bedsheet. The exhibition reveals his deeply self-reflexive creative process – driven by an incessant questioning of how and why he should be painting. Flora is a fine example of this extensive obsession. She had to seek osteopathic treatment to recover from the months of modelling Freud put her through (something which he asked of many of his muses).

While he completed many commissions (from Kate Moss to Big Sue), Freud repeatedly returned to his own image. It becomes apparent, after walking through each section of the gallery, that the central theme of his work is reflection. This is made explicit by the fact he often painted with mirrors, dotted around his studio. Freud preferred them to photographs and enjoyed the surprise that new angles forced him into. Two meanings of reflection are at play here in his work: in the external tools he used and the internal moments he captured. ‘Interior with Hand Mirror’ (1967) and ‘Small Interior (Self-portrait)’ (1968) propose how reflective surfaces can create depth, how a perspective can be physical, temporal, and psychological. The mirror selfie, it would seem, has long been a popular mode. The tradition extends long before Kim Kardashian, back to Rembrandt, Kahlo, and now Freud.

In his later period, and the final stages of the exhibition, Freud’s reflections reach full maturity. The knotted, frayed, almost sedimentary surface of ‘Self-portrait, Reflection’ (2002) offers a frank depiction of the ageing process. In ‘Painter Working, Reflection’ (1993), Freud paints himself nude (for the first time) in his 70s. He is bare, save some unlaced boots, and scrutinising of every feature – calves, nose, genitals – paint palette and knife in hand. Freud meets his own image with ruthless honesty. His self-observations are never narcissistic, but always obsessive.

Throughout his life, Freud’s own image never left him. It was where he – like we – went to scrutinise and find the ‘trouble’ that occurs when we look at ourselves. The Royal Academy’s exhibition shows us one man anxiously at work, talking always of insufficiency. Yet we leave with a palpable sense of accomplishment: that Freud has earnestly given us something of himself.

I would recommend this exhibition to anyone in London with a few hours to spare. There is one month left to see it in person, and the RA are also broadcasting it on-screen from the 14th January.

https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/exhibition/lucian-freud-self-portraits#articles