It’s December 2019, and temperatures lie below freezing in the North. As I sit cosily sipping hot cocoa in front of the fire, Breaking News flashes onto the TV. Today’s headlines are, as usual, tediously bleak; half a million Whirlpool washing machines have been recalled, National Rail ticket prices have increased yet again, and Boris is making plans for Brexit. Yet, the fourth headline is the bleakest of all: Australia is ablaze.

After the hottest year on record, accompanied by continuous drought and relentless bush fires since September, Australia is currently seeing some of the worst impacts of climate change. Whilst its highest historical temperature still remains at 50.7 degrees, as recorded in January 1960, in early December north-west Victoria saw over a week of plus-forty degrees Celsius, and Australia’s north-eastern coastal areas were hardly any better. Needless to say, the inland ‘bush’ quickly became a lost cause.

It seems odd to me that such climate crises can still be advertised as Breaking News. In a world which has well-understood the issue of climate change since the 1960s, after sixty years it is painful, in fact excruciating, that there is no better method of informing the public. Yet, the media, alongside its ‘Breaking News’, presents the climate crisis exactly as it is viewed by the majority; as a short-term, solvable dilemma, only in need of a few quick-fire solutions and there’s the job done. Dusted. Business as usual, collect your pay-cheque.

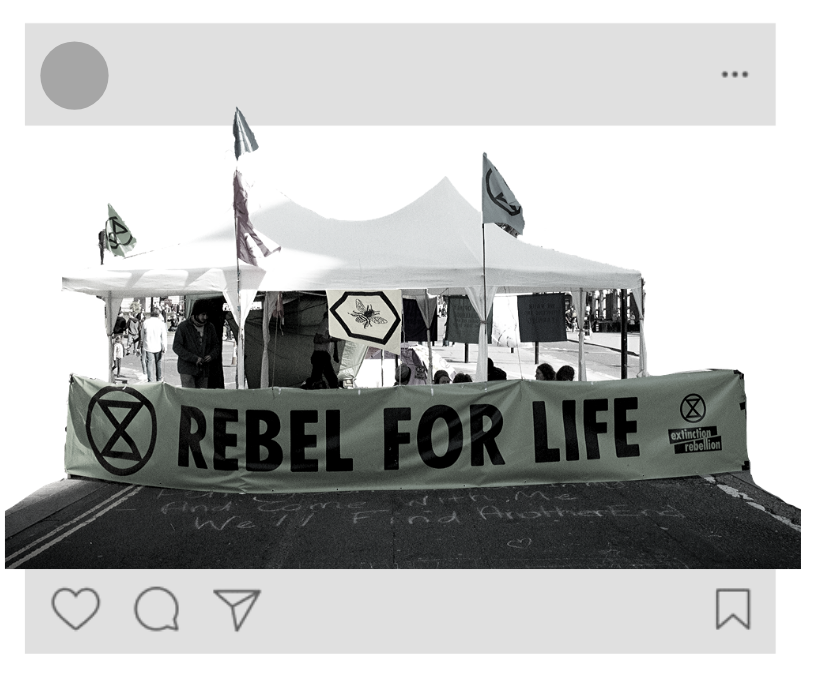

However, as the likes of Extinction Rebellion force us to focus less on the word ‘climate’ and more on ‘crisis’, it has become increasingly clear that the global reactionary approach to the climate crisis desperately needs to evolve. We have no time to sit and mourn the collapse of a single ice cap or, more brutally, the death of a few Arctic polar bears; we are now facing a human crisis, with human impacts. To stop large-scale death and destruction in the world’s poorest areas, we must act now.

This is no Breaking News, and I won’t pretend that anything I’ve said so far is revolutionary. Yet, such realisations must prompt action, not only within the respective frameworks of individual and governmental action, but also within the framework of the media. The year 2019 saw a tidal-wave of over 170 global media outlets, such as The Guardian, CBS News and The Huffington Post, all agreeing to the ‘Covering Climate Now’ pledge to actively cover climate crisis-related incidents.

Whilst this pledge was only intended as a week-long agreement surrounding the September UN Climate Action Summit in New York, the majority of media outlets involved have kept this initiative as part of their framework, with The Guardian taking their role in public engagement with climate change particularly seriously.

Yet, even in the year following the apocalyptic prophecies of Extinction Rebellion’s co-founder Roger Hallam, both public and governmental engagement with the climate crisis is far from where it needs to be. At this stage, the majority of us have heard enough to understand the unrivalled level of suffering that is about to ensue, and we know enough about the crippling complications climate change could bring. The issue is, rather, that we cannot see.

To my disheartenment, a quick Google search of the words ‘climate change’ will bring up an influx in imagery of falling ice-caps, desiccated and desertified land, and raw-boned polar bears. The worst of climate-crisis visuals will merely display an image of the globe, perhaps half-inundated with fire, or even simply fill-coloured red. A number of charred chimneys appear, a few wildfires, and a lone burning tree.

Whilst none of these images could be termed factually inaccurate, the unfortunate truth is that current climate visuals are not only unsatisfactory in conveying the urgency of this crisis, but they are also dangerously far from reality. With a recent prediction of 529,000 adult deaths by 2050 due to climate-change related food shortages alone, we will not only be mourning the struggling polar bears, or the dying endemic species of Kangaroo Island. We will be mourning human loss of life, resulting from some of the most inhumane suffering the world has ever seen.

Hence, current climate imagery is vastly inadequate. By presenting such soft, ‘family-friendly’ and western-specific visuals, media platforms are not only diluting the reality of climate change, but they also run the risk of reducing support. In a world where two of the largest polluter-nations are governed by climate-deniers, Australia’s Scott Morrison and America’s Donald Trump, the G7 countries are already on a slippery slope. As one of the wealthiest and most resource-rich nations in the world, with a great power to implement mitigation and adaptation methods, we cannot risk such a dampening of the climate narrative. Media platforms must provide imagery which matches, or even exceeds, the aggressive and urgent tone of Extinction Rebellion.

The Guardian newspaper were, in a bold yet heroic decision, the first to realise and implement such a change. In October 2019, journalist Fiona Shields published a piece explaining the need for such fresh imagery, which begins by stating, ‘we want to ensure that the images we publish accurately and appropriately convey the climate crisis we face.’ Accompanying this piece were numerous vaguely distressing images, including one of a Portuguese villager shouting for help as a wildfire approaches, one of a man and his child wearing smog-masks in Waltan, and another of a young boy drinking water in a toxic slag-heap in Zambia.

Yet, scrolling further through the article, a number of surprising images appeared. In a rather wholesome feature, a father pushed his son on a slow-sled in the Cotswolds, and a woman played with her dog in the snow of Moscow. Other visuals included a ram-packed Bournemouth beach on a bank holiday, slightly more suggestive of the traditional, tabloid representation of global-warming we have seen before.

I could not possibly deny that climate change will increase the frequency of extreme weather events, such as heavier snowfalls in the winter and soaring temperatures in the summer. Such phenomena are already occurring; Cambridge University Botanical Garden recorded a temperature of 38.7 degrees-Celsius in 2019, beating the highest-temperature record set in Southampton in 1976. To deny such a reality would be to argue against scientific fact. Furthermore, I could not deny that some of these altered weather events may be, well, enjoyable. For the fortunate few escaping the suffering caused by drought, wildfire and flooding, I’m certain a hot day at the beach would be more than welcomed.

Yet, in the UK, where compulsory Climate Change Education was only enforced in 2008, I wonder whether such positive climate imagery is useful. It is safe to say that the majority of our nation do not recognise the term thermal expansion, nor understand the complex feedback mechanisms of greenhouse gases such as methane. Without a basic education of climate change, how could readers of The Guardian possibly understand that a happy image of a boy playing in the thick snow is supposed to represent emergency, and indeed crisis? By confusingly paralleling images of deadly destruction with those of happy childhood experiences, we run the risk of further alienating the masses away from supporting the climate crisis. Even Donald Trump, the most powerful politician of our current world, seems to believe that the increased frequency of cold weather events is grounds for global-warming and climate denial.

Despite the positive changes made by media organisations such as The Guardian, we are still far from realistic, honest climate representation. To expose the true reality of climate change via the means of visual representation, we need to first of all recognise, and be held accountable for, our own historical actions. Whilst Britain may not currently be the largest polluter, it unequivocally led the industrial revolution of the 18th century, which caused a 260% rise in conglomerate greenhouse gases, as recorded in 2012.

The UK have, in fact, pledged net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, but we are still far off this target. With the likes of Boris Johnson leading our country, such a task may be even more challenging still. Although British climate imagery has often depicted smoking chimneys reminiscent of our industrial days, such an admittance is not enough; we must depict and accept responsibility for the deaths and suffering that have been caused by our pollution, not only during the era of the Industrial Revolution itself but within our modern world. Such an acceptance cannot be conveyed by polar-bear, glacial-melt imagery.

Yet, the question still remains as to whether more brutal imagery will successfully stimulate climate action. The success of the Band Aid & ‘Feed the World’ campaign fills me with a sense of optimism; despite utilising highly distressing imagery of the Ethiopian famine, the campaign raised over £127 million in 1984, and increased widespread awareness of an issue that had previously received little support. As the world will see 1.7 times more demand for food by 2050 due to uncontrollable population expansion, it is not unrealistic to say that food security will soon be threatened across every continent. With this reality in mind, we should not limit ourselves to images of desertified land, failed crop harvests and biblical swarms of locusts; like the Band Aid campaign, climate crisis imagery is well within its right to illustrate human suffering, famine, or even death. Dark and drastic as this may be, it could be the only answer to saving our planet before its own self-combustion. As those sitting at home watching Live Aid picked up the phone to donate in 1985, perhaps such heavy imagery may be a wake-up call to our modern viewers today. The brutal reality is that the majority of us don’t give a fig about polar bears or ice caps; people care about people.

However, rebranding the imagery of climate change cannot solely be focussed on imagery of death and destruction, the implications of climate change are much more complex than that. In 2018, the UN recognised climate change as a driver of migration for the first time, when citizens of the Pacific island Kiribati fled their homes due to flooding. Migration will, in fact, be one of the most significant consequences of climate change. With the strengthening of El Niño and La Niña events, and the increased frequency of ‘freak’ weather increasingly making more areas of the world’s land inhabitable, the influx of climate migrants will inevitably multiply year-by-year.

Even some of the world’s wealthiest countries such as Australia, which is still being ravaged by bushfires, do not have the resources to cope with this impending migration crisis. When depicting climate change in the media, we are once again well within our right to depict imagery of migrants, borders, and migrant detention centres. Again, these are all realistic results of the climate crisis, and, to combat this crisis effectively, we need to accept these realities as soon as possible.

I have only skimmed the surface of the brutal realities that the climate crisis will bring with it, and, thanks to the compulsory inclusion of climate change within school curricula since 2008, I am sure most of you reading this will be well aware of this fact. I am hopeful, in fact confident, you will all agree that the time is now for climate rebranding. With the urgency and immediacy of this crisis, we can no longer play it safe with pretty polar bears and imposing ice caps. To ensure greenhouse gases do not exceed the 1.5 degree ‘tipping point’, we need both a governmental and individual wake-up-call to action, and such action needs to happen now. In accordance with the immediate nature of the crisis, we require not only aggressive words in the media, but also urgent and aggressive climate visuals. The narrative can no longer be one of delay; at this point, any delay is costing not only livelihoods but lives, and the survival of the human race needs to be our priority.