It is rare to hear about a life as extraordinary as that of Muriel Gardiner. A student who left Oxford for an underground socialist movement in Red Vienna, a Jewish woman who saved countless lives from Nazi Germany, a woman who spent the entirety of her life, in her lover Stephen Spender’s words, “dedicated to doing good to others”.

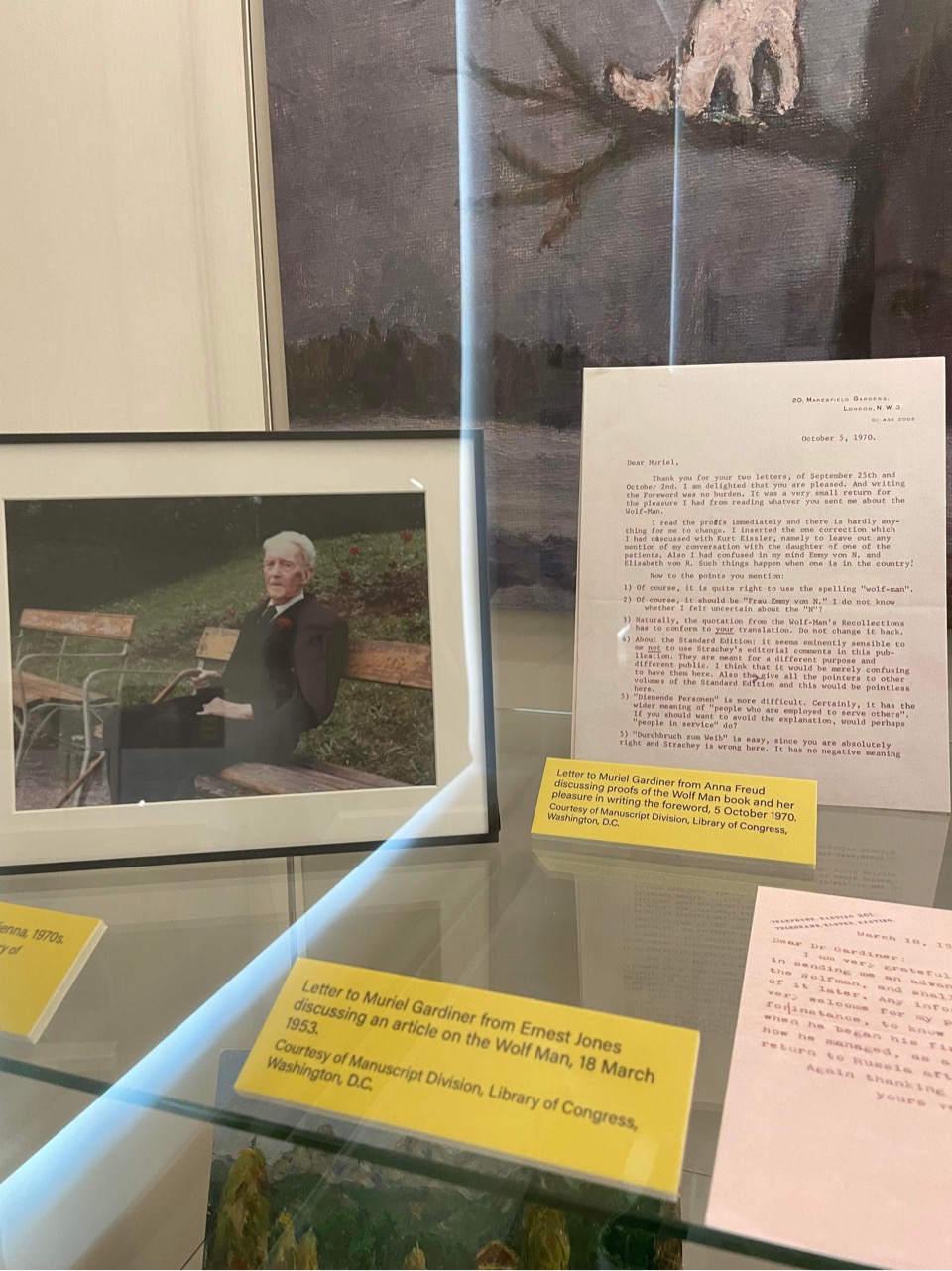

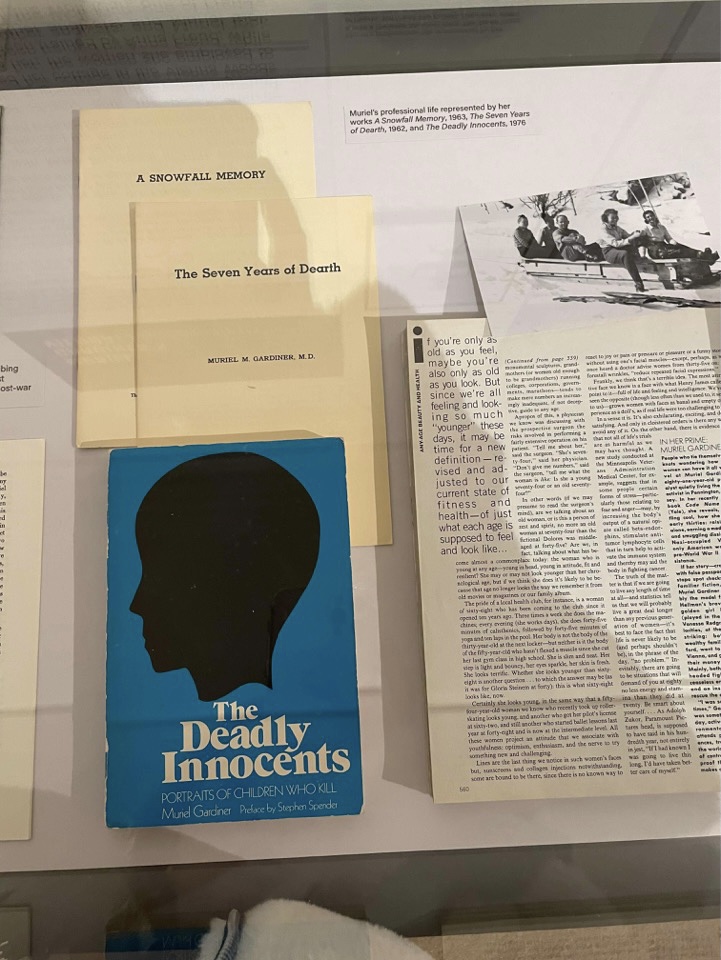

The new exhibition – “Code Name Mary: The extraordinary life of Muriel Gardiner” at the Freud museum runs until January 2022 in London. I had visited museum in Vienna, to see, much to my disappointment – a replica of the entirety of the contents of the house in Hampstead. Yet, it is something about the quaint little gallery in the house in London, with it’s strange collection of antiques, that really makes it feel as though Freud might look over at you from round behind the desk, and greet you. Visiting the Freud museum is always a fascinating experience, from seeing the original couch lodged in the corner of the beautiful little house in Hampstead, to the exhibitions, and the paintings of the Wolf Man. It was, however, striking to realize that we would know almost nothing about the famous “Wolf Man” without Muriel – the woman who published the account of Freud’s most famous patient, and further, wrote a book about the account herself.

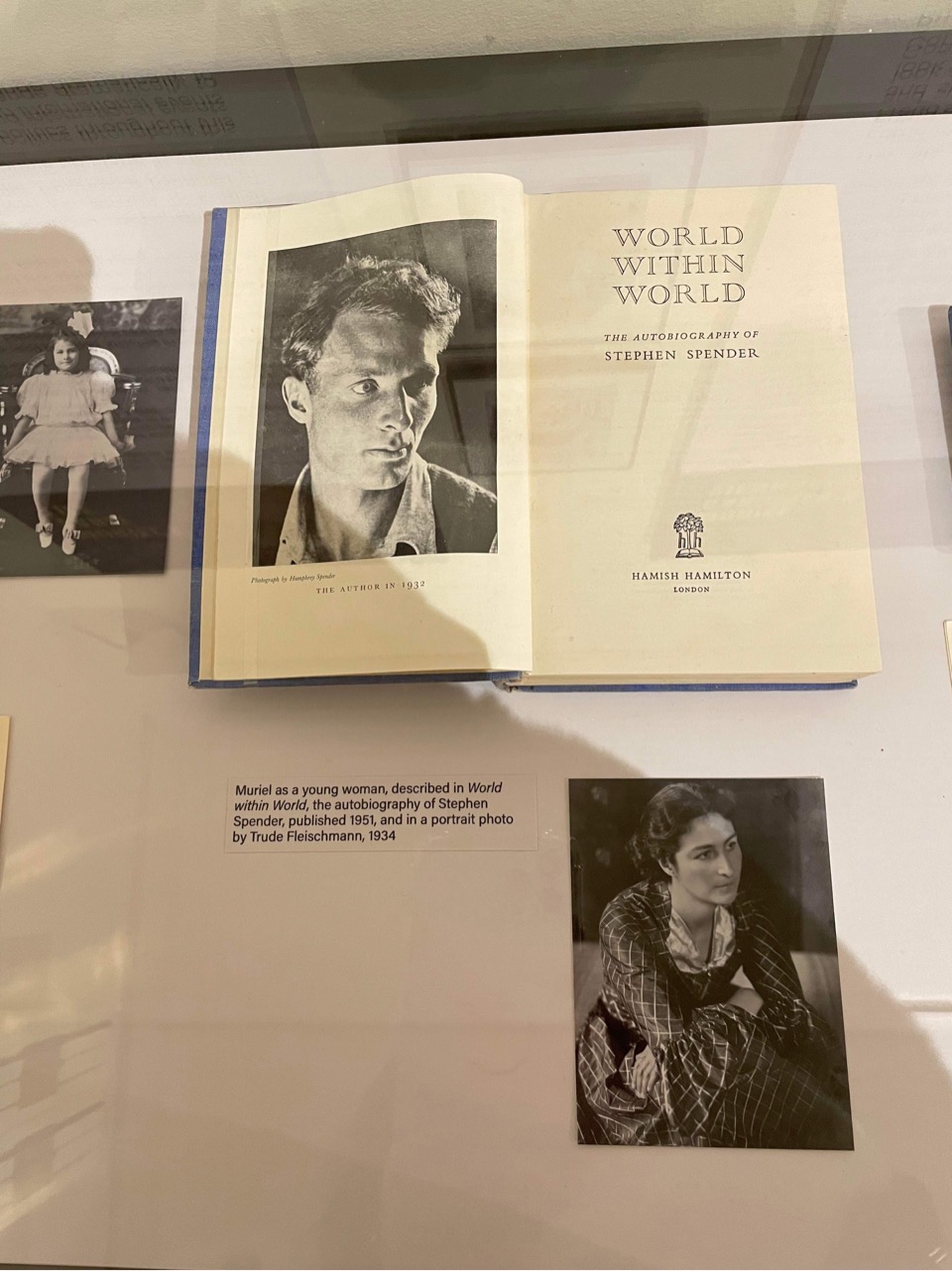

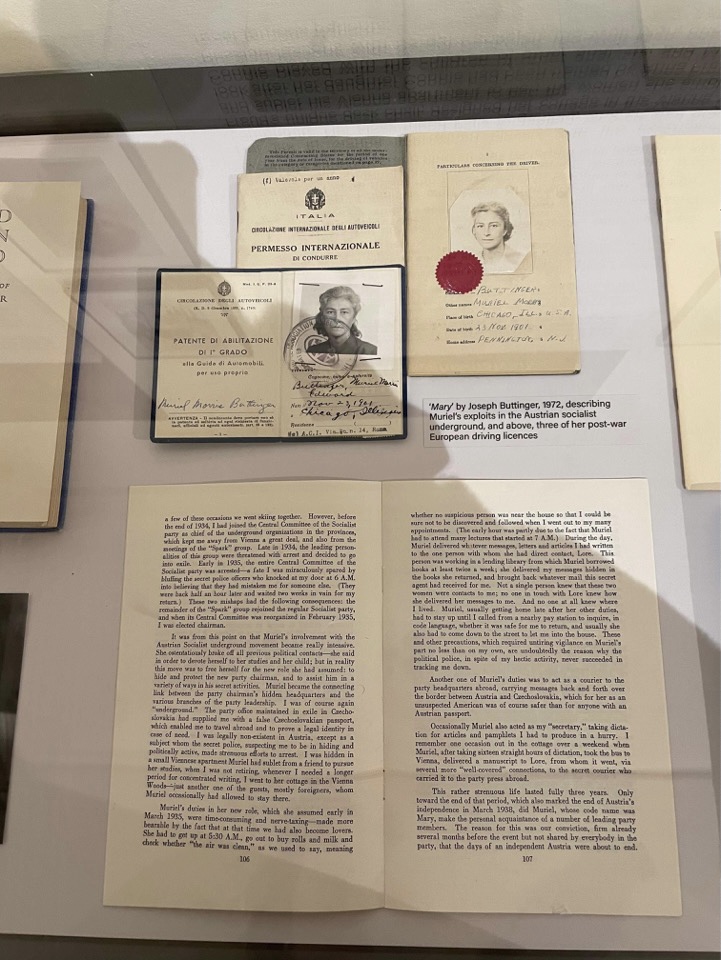

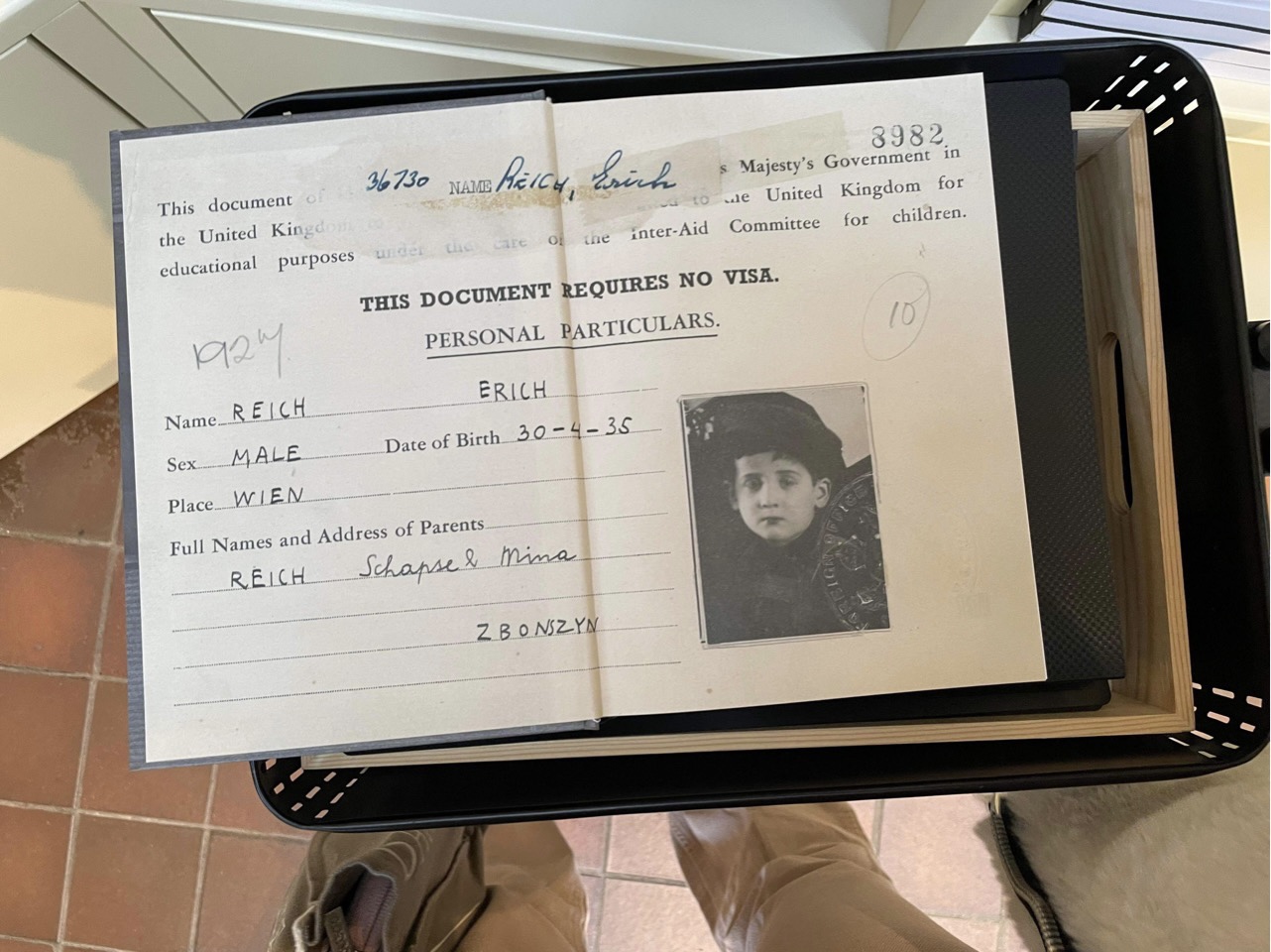

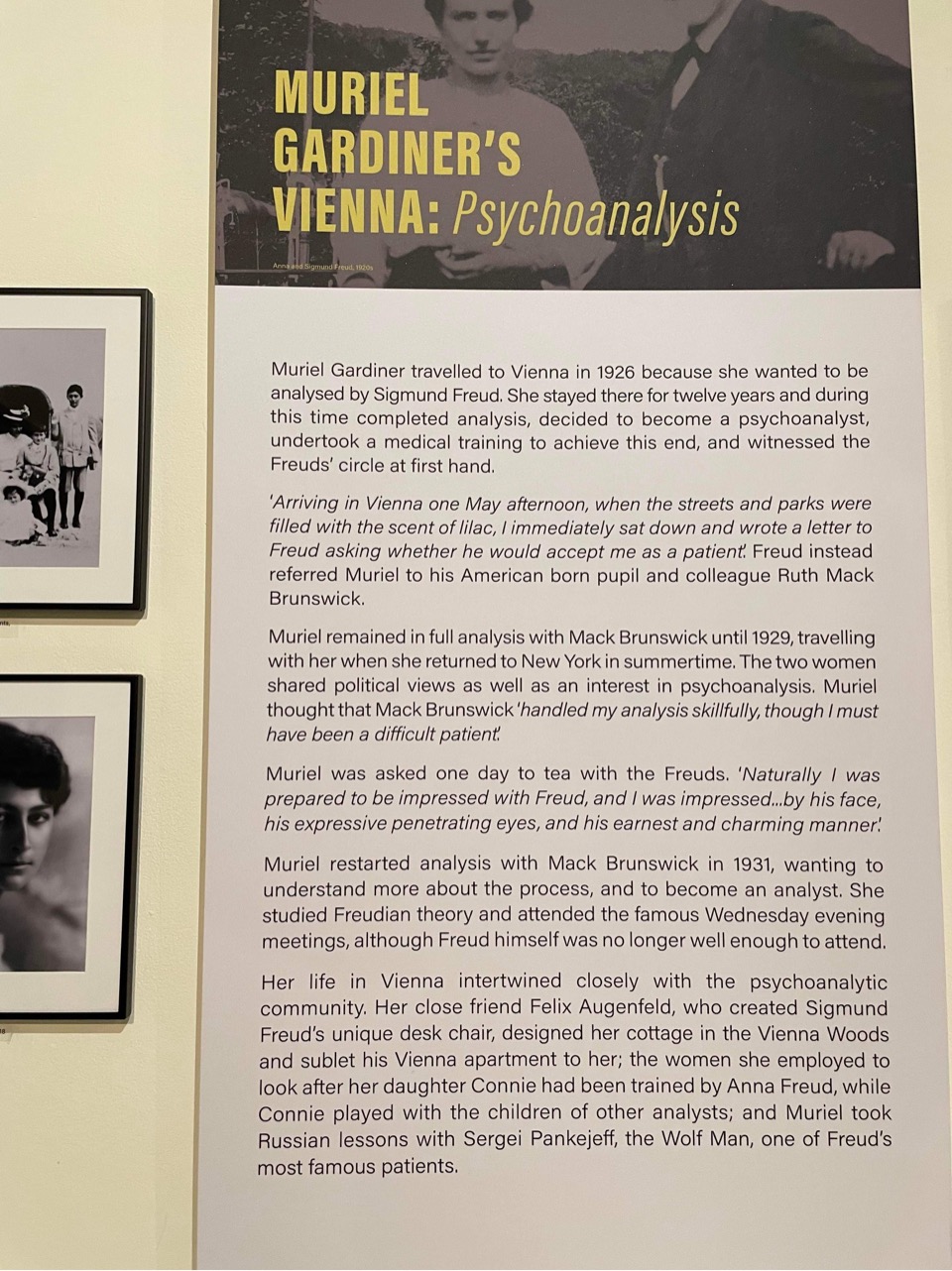

I was drawn to Muriel because of her famous affair with Stephen Spender in Vienna, her underground socialist activities in Vienna, the way in which she saved countless individuals from the Nazi regime, her time at Oxford… in fact from the moment I heard of her, and the controversy surrounding Lillian Hellman’s character Julia (who was, in fact, Muriel), I was intrigued to know more. Muriel attended Oxford in the 1920s, before travelling to Vienna, initially for psychoanalysis. She was defiant whilst at Oxford, finding it “bleak, rigid, and unfriendly to women students” at her women’s college which she felt was like “a girl’s boarding school.” Her sense of purpose was always in politics, in righting perceived injustices. When she travelled to Vienna, she joined a radical underground communist group committed to Red Vienna, smuggling passports and money for her comrades under her code name, “Mary”. She housed anti-fascists, hiding them in her cottage, and eventually ended up leaving Spender for the leader of the Austrian Revolutionary Socialists, Joseph Buttinger, whom she married.

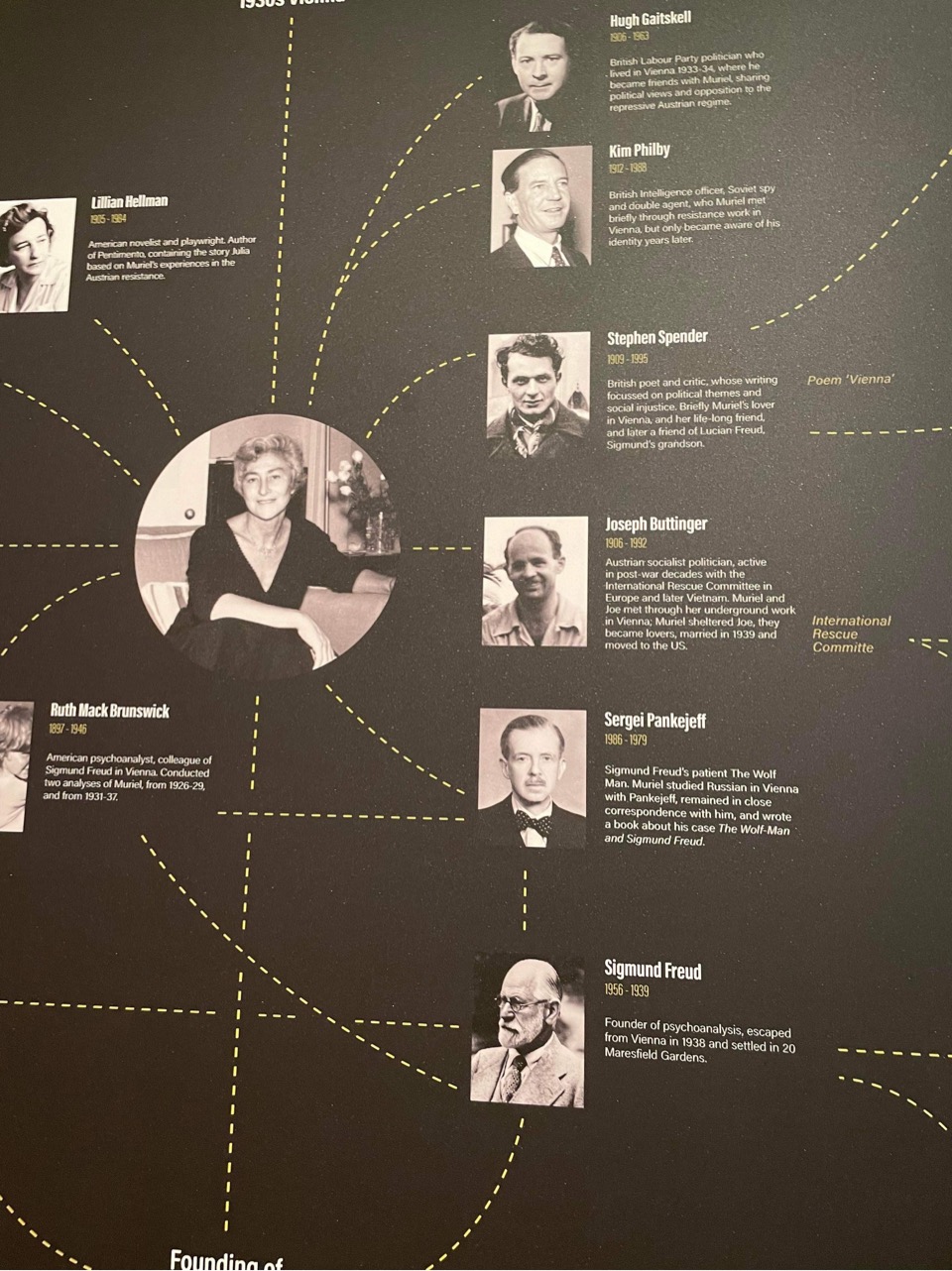

At the centre of the gallery is a large notice board with the word connections writ in large. A photograph of her in a glamorous black dress sits at the centre, and around her we see the faces of those she was entangled with in Vienna. We see Kim Philby, the famous Soviet spy, who she recalls meeting in her memoir and only connects face to name thirty years later, when she happened to pick up The Third Man by E.H. Cookridge, a biography of Philby; the poet Stephen Spender (Spender’s first sexual relationship with a woman was with Muriel), who recalls his time in Vienna in his poem of the same name; Sergei Pankejeff – the famous Wolf Man, and a patient of Sigmund Freud; (Muriel herself wrote a book about his case entitled, The Wolf-Man and Sigmund Freud); Freud; Joseph Buttlinger; Albert Einstein – a good friend of hers; and several other names, all of which testify to the network of brilliance she interacted with and assisted during one of the darkest periods of all time. It is enthralling to think about her time in Vienna, her involvement in the underground, as revealed in her memoir which deals with the hunted lives of her comrades, but also evokes her personal relationships, fragments of memories she clearly treasured for most of her life.

She is most famous as Juliain Lillian Hellman’s book Pentimento, which was later filmed as Julia – a film which stars Vanessa Redgrave. The controversy surrounding this film is perhaps one of the most fascinating aspects of the entire story. When the book Pentimento first appeared, her friends began to call her, insisting that she must be “Julia” as there were no other American women who were deeply involved in the Austrian anti-Fascist or anti-Nazi underground. Although she says that she tried to write her own autobiography prior to the publication of this book, it seems like the book is what prompted her to tell her own story. She was even involved in founding and funding the Freud museum itself, and seems in this way responsible for carrying on the legacy of all of those names surrounding hers on the Connections chart, even as hers has generally faded into obscurity.

An article written about the exhibition declares her to be “the most thrilling person you’ve never heard of”. It is bizarre that she lacks fame, given that she was perhaps one of the greatest activists amidst a series of incredibly famous names. An heiress, she could have remained in the States – but instead she came to Europe and spent years of her life smuggling people out of a war torn land. Jewish heroines like Gardiner deserve exhibitions, celebrations, books, and fame. They do not deserve to fade into obscurity, forgotten by generations. Reading her autobiography, hearing her compassionate voice and her radicality speak for itself, is an experience to treasure. I would highly recommend it.

Image credit: Tamzin Lent