There can’t be many people who have inspired both an opera and a U2 stadium anthem. President Lech Wałęsa may well be one of the most famous electricians in the world, having been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1983 for his non-violent agitations against communist rule in Poland as leader of the Solidarity movement. The first recognised independent trade union to be recognised in a Warsaw Pact country, Solidarity directly caused the end of communist rule by pressuring the government to hold an election in 1989, which saw Wałęsa become the first President of Poland to be elected by popular vote.

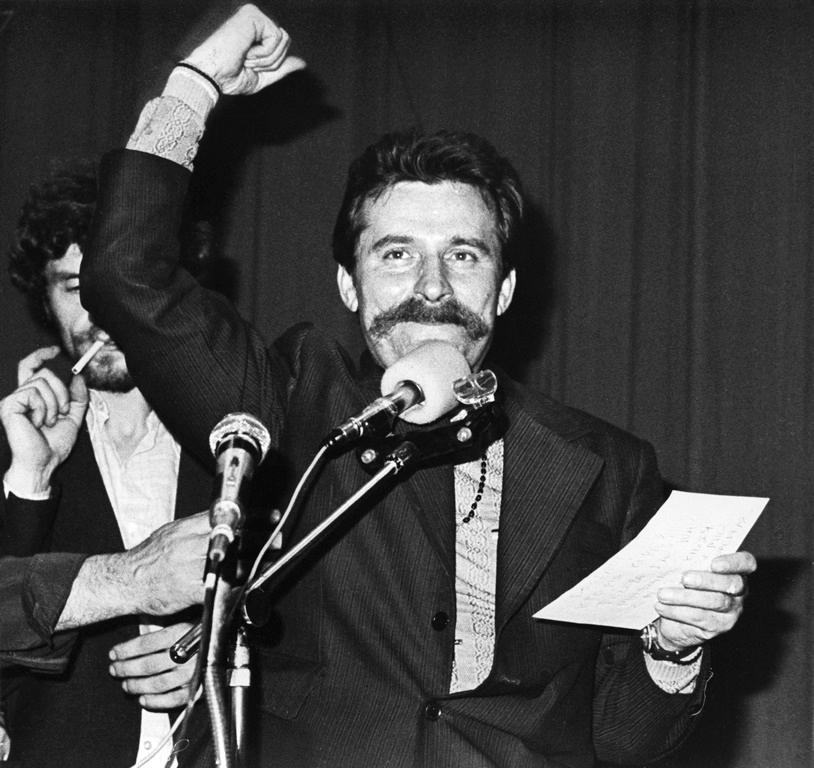

We speak via an interpreter over Skype. Wałęsa is in Gdańsk, the city which includes the enormous shipyards where Solidarity was born. He is an animated speaker, gesticulating freely to emphasise important phrases. He still has his iconic moustache which made him instantly recognisable in photographs from the time, albeit now white and slightly more groomed. He’s wearing a grey rollneck sweatshirt bearing the KONSTYTUCJA – ‘Constitution’ – slogan which has become a symbol of protest against the populist government. He wore a similar shirt to the state funeral of President George H.W. Bush, and has even said he will ask to be buried in it.

Wałęsa describes himself as a practical man, which affects not only the way he approaches problems, how he breaks their solutions down like an instruction manual. Practicality, to Wałęsa, emphasises action and learning from one’s mistakes for the future, even if those mistake are painful. “I never forget anything I have practiced. I have eight children with my wife!” he says mischievously at one point

Wałęsa’s success as a labour organiser can in part be attributed to this practical approach, and his persistence in organising industrial action and negotiations. He attributes his drive to stand up to communism, despite its risks, to his upbringing. “I took it in with my mother’s milk”, he says, adding that his family had a history of anti-communism. “Whenever there were conversations about anti-communism at home, I lapped it up.”

The People’s Republic of Poland was formally established in 1952, seven years after the Red Army ‘liberated’ Warsaw and established a provisional communist government.

“The communist system was imposed on Poland after the war. It was never accepted by Polish people,” Wałęsa says as we discuss the history of anti-communist resistance in the country. The post-war years saw severe political repressions, and a state of near civil war as partisans loyal to the government on exile who had once fought against the occupying Nazis turned their attention to the communist authorities. Both partisans and civilians were subject to mass arrests and executions. Anti-communists responded by attacking prisons and detention camps, attempting to free the political prisoners they held.

“In the 1940s and 50s we tried an armed struggle – that didn’t work. In the 60s and 70s we tried strikes – that didn’t work”, he says, reflecting on how opposition to the Communists changed. The strikes of the 60s and 70s may not have led to the fall of the regime, but they taught Wałęsa and other activists hard lessons which led to the later success of Solidarity. March 1968 saw protests erupt across the country against the government over the high price of food, and frustration that the promised liberalisation under Gomulka’s leadership had failed to materialise. The month also saw protests by students, writers and intellectuals who were branded as Zionists, with the explicit implication that the dissidents were not Polish.

Wałęsa encouraged workers at the Gdansk shipyard not to join the supposedly spontaneous protests against the dissidents which were sanctioned by the government. The shipyard because the centre of huge protests in December 1970 against rising food prices. The strikers, which spread to cities across Poland were met with gunfire, killing 45 and injuring 1000 people. The outcome cemented Wałęsa’s commitment to organising free trade unions, which were unaffiliated from the state. He lost his job at the shipyard, was arrested multiple times as punishment for this agitation.

But he got results. Further mass-protests and strikes in protest against high food prices, and in favour of gaining greater civil liberties erupted in August 1980. The strike in Gdansk was ignited by the firing of Anna Walentynowicz, a crane operator who had been involved in organising earlier protests. The striking workers successfully pressured the shipyard’s management into meeting their demands over pay and labour rights. The resulting Gdańsk Agreement, signed by the strikers and communist authorities, permitted the formation of trade unions which were unaffiliated with the state. Solidarity was founded as the country’s first free trade union on September 22nd.

“Many of the people at the top of the Communist pyramid studied in the West,” Wałęsa explains. “They were slightly sceptical and they weren’t so much trying to defend Communism as they were trying to defend their positions of power. So it was possible to do a deal.”

The Gdansk agreement didn’t stop the government from imposing martial law in December 1981 to counter political opposition and Solidarity, which represented a third of the working population. Wałęsa was arrested, as were 6000 other Solidarity activists, and imprisoned for almost a year. Solidarity moved underground, albeit with the backing of the CIA who provided funding, organisational advice, and helped them spread their message through clandestine newspapers. Wałęsa tells me that Solidarity’s resistance through his time is thanks to the organisation’s determination and reasonableness: “Communism couldn’t combat that.”

After his release, Wałęsa was awarded the 1983 Nobel Peace Prize for “non-violent struggle for free trade unions and human rights in Poland.” He didn’t collect the award in-person in Oslo, fearing that he would not be allowed to re-enter Poland. His wife Danuta accepted the award on his behalf.

Despite the international acclaim Wałęsa has received for his undoubtedly enormous contribution to the course of history, he has been facing accusations that he had acted as a paid informant of the secret police in the 1970s. Wałęsa has denied these accusations, claiming that they are politically motivated. A special court cleared him of charges of collaboration in 2000. The controversy reared its head again in 2016, when documents which appeared to show his involvement were found by the Institute of National Remembrance, an organisation dedicated to identifying and archiving crimes committed under the Soviet and Polish Communist regimes. Again, Wałęsa defended himself, saying that the documents were forged to discredit him. Historians have acknowledged that the secret police used to fabricate documents to compromise members of the opposition.

What made Solidarity different from previous movements? The movement’s size and breadth meant that it encompassed otherwise polarised facets of Polish society: the anti-communist left and political right wings, liberals and nationalists, and the intelligentsia and workers, as well as atheists and believers. Wałęsa tells me that the hatred of communism acted as a common denominator between these disparate groups. “Through a system of trial and error, we realised if we all came together in solidarity we could achieve success. We realised we had to be a monolith to stand against communism.”

“When the Soviet Union collapsed, we lost that common denominator. In modern times, we no longer have that to unify different people.”

Wałęsa’s answers become longer as our conversation turns to the present political situation in Poland. His presidency saw Poland transition towards a free-market economy under the Balcerowicz Plan. He tells me he sees the present political order as going through a transition of its own – a transition from an age where nation states define the world, to an age of continents and globalisation which he believed is yet to solidify. He calls this in-between state the “Epoch of the Word and Discussion”.

What kind of discussions are taking place in this epoch? Wałęsa breaks the answer down into three questions. What should the coming epoch be based on? He identifies a conflict between people who want to build a society on freedoms, and those who say that we can only start talking about rights once the core values of a society have been laid out.

What should the economic system be? “Certainly not communism,” he makes clear. “Not because it’s good or bad, but because it’s never worked anywhere.” But equally, the current form of capitalism won’t do. “It worked for the old system of states and countries. But it led to a rat race of nations, which led to mass unemployment. Many people just couldn’t keep up with the pace.”

His third question is one I knew I wanted to explore the moment our interview was confirmed: How do we deal with the demagoguery of populist politicians? “Populists and presidents give the same diagnosis, that everything needs to be changed. It’s just that the populists’ solutions to the problem are wrong.”

Wałęsa is a fierce critic of the current Polish government, who he has accused of attacking the rule of law and democracy. In 2020, the NGO Freedom House downgraded its assessment of Polish democracy as ‘consolidated’ to ‘semi-consolidated’. In the five years since the Law and Justice Party (PiS) came to power in 2015, they have used their control over the formerly independent body responsible for appointing judges to promote party loyalists to the newly created Disciplinary Chamber. Polish judges and international observers feared that the chamber would put pressure on the judiciary to issue rulings which fall in line with the government’s wishes.

“The problem is that we’re only learning democracy, we’ve never had it before,” he says.

He sees the situation as so dire that he has claimed a ‘dictatorship’ is being created in Poland. “In Poland, we are less than 50% of a practical democracy,” he says, according to the ‘Wałęsa Model of Practical Democracy’, which he uses to break the system down into three practical areas. Poland scores full marks for its constitution and legal system, but voter turnout in elections is low, and Wałęsa doesn’t think many people are willing to stand up for change.

Poland’s political troubles extend beyond the country’s borders and into Europe. Along with Hungary and Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz Party, the PiS frequently clashes with Brussels over the bloc’s promotion of progressive values and attempts to encourage the rule of law. Wałęsa has said that Poland should be thrown out of the EU over the PiS’s advances on the judiciary. But he also opposes ‘Polexit’, and speaks at Pro-European demonstrations alongside Donald Tusk, the former President of the European Council, who was an active member of Solidarity’s Youth Committee.

“I’ve been saying this for twenty years: every vehicle must have a driver. The fight against Communism was a Polish matter which involved Polish people. Once that battle was won, we came to the challenge of trying to rebuild Europe. I passed this challenge on to the Germans.

“I would like it if Poland was the driver. But Poland doesn’t have the resources or influence. Germany does. Together with France and Italy, they have the ability to enact changes and find two solutions for each problem.”

But implementing solutions in the EU requires consensus between member states. Poland and Hungary recently vetoed the bloc’s COVID-19 recovery plan and €1.8 trillion seven-year budget because of plans to link a member state’s access to funds to their adherence to the rule of law.

“If we can’t do it with Poland and Hungary in the camp, let them destroy the European Union,” he says bluntly. “And five minutes later, we’ll propose a new one.” In order to access the rights and opportunities presented by this new union, prospective members would have to agree to a fresh series of obligations. “We have to establish these rights and obligations in such a way that this nonsense we see couldn’t possibly happen.”

Wałęsa now travels the world promoting Poland’s non-violent transition to democracy, speaking about human rights and the challenges and opportunities posed by the Epoch of Discussion he told me about. He has a Wikipedia page dedicated to the many awards, state decorations, and honorary degrees from across the world. Wałęsa never studied beyond his vocational training as an electrician, which he tells me he regrets. “If I’d had a university education, I would have ten Nobel Prizes, not just one!”

In the model of many US Presidents, Wałęsa founded a eponymous institute to preserve the memory of the Solidarity movement and its place in history, and to educate future generations. I end by asking him what message he would give if he was speaking to an audience of students at Oxford.

“My generation opened up opportunities for your generation. The world is yours. My generation has broken down a lot of barriers. Now you have to make the best of it, without these barriers and borders. It’s up to you to decide whether my generation has succeeded or not. Because if you fail, you’ll blame us.

“Previous generations were scarred by wars and revolutions. Nobody trusted anyone. It’s up to you to convince people and open up your minds to other people. Because right now, the populists have taken over the initiative and everyone is sitting around and watching.”

With thanks to Anthony Goltz, Roman Picheta and Aleksandra Słowik.

Image Credit: The Lech Wałęsa Institute