When it comes to housing affordability, Oxford is well-behind its world-class peers. Researchers and academics at the University of Oxford are faced with some of the highest housing costs in England and elite academia. While Oxford is infamously an expensive city, it also has a reputation of elitism and prestige. It would be expected that employees at one of the world’s oldest universities, where three course meals in ornate halls are a weekly occurrence, could afford to live in the ancient city. This is not the case.

Oxford’s severe lack of affordable housing has been highlighted in recent years by city councillors, the Oxford branch of the University and Colleges Union, university staff and administrators. The university and other groups are taking steps to improve housing supply and commuting benefits. However when compared to other comparable institutions, particularly in the United States, Oxford is far behind in terms of affordability – for reasons that go far beyond housing policy alone.

Housing costs high across the sector

The life of an academic at Oxford or Cambridge and that of someone occupying a similar post at a top Ivy League school or elite research university like MIT or Stanford is different in many ways. Those working in the UK generally receive greater social benefits, like maternity and parental leave. By contrast, salaries and scholarships starting at the graduate level are often more generous in the US. There is, however, one domain where top tier UK universities, and Oxford in particular, continually lag behind their American counterparts: housing affordability.

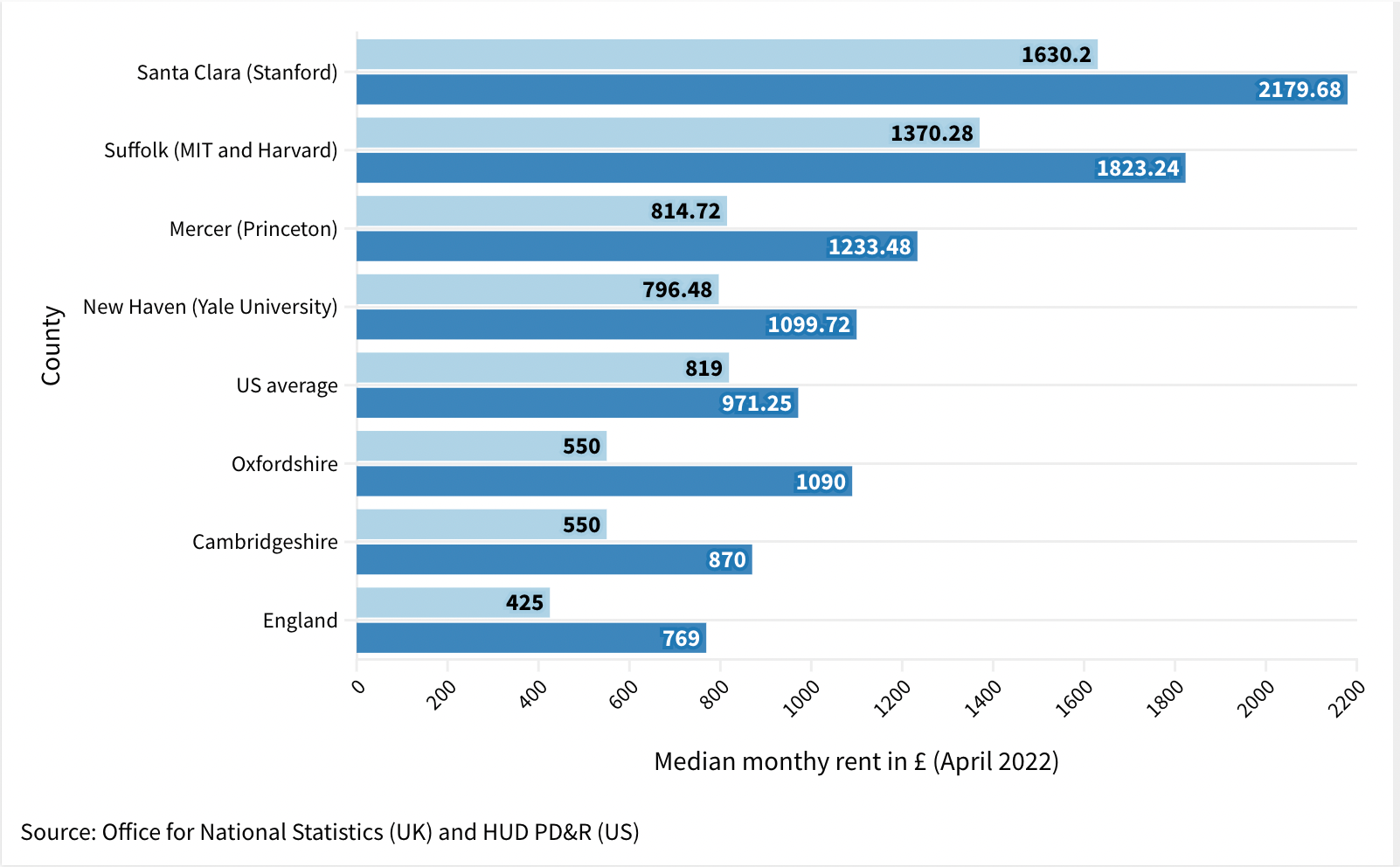

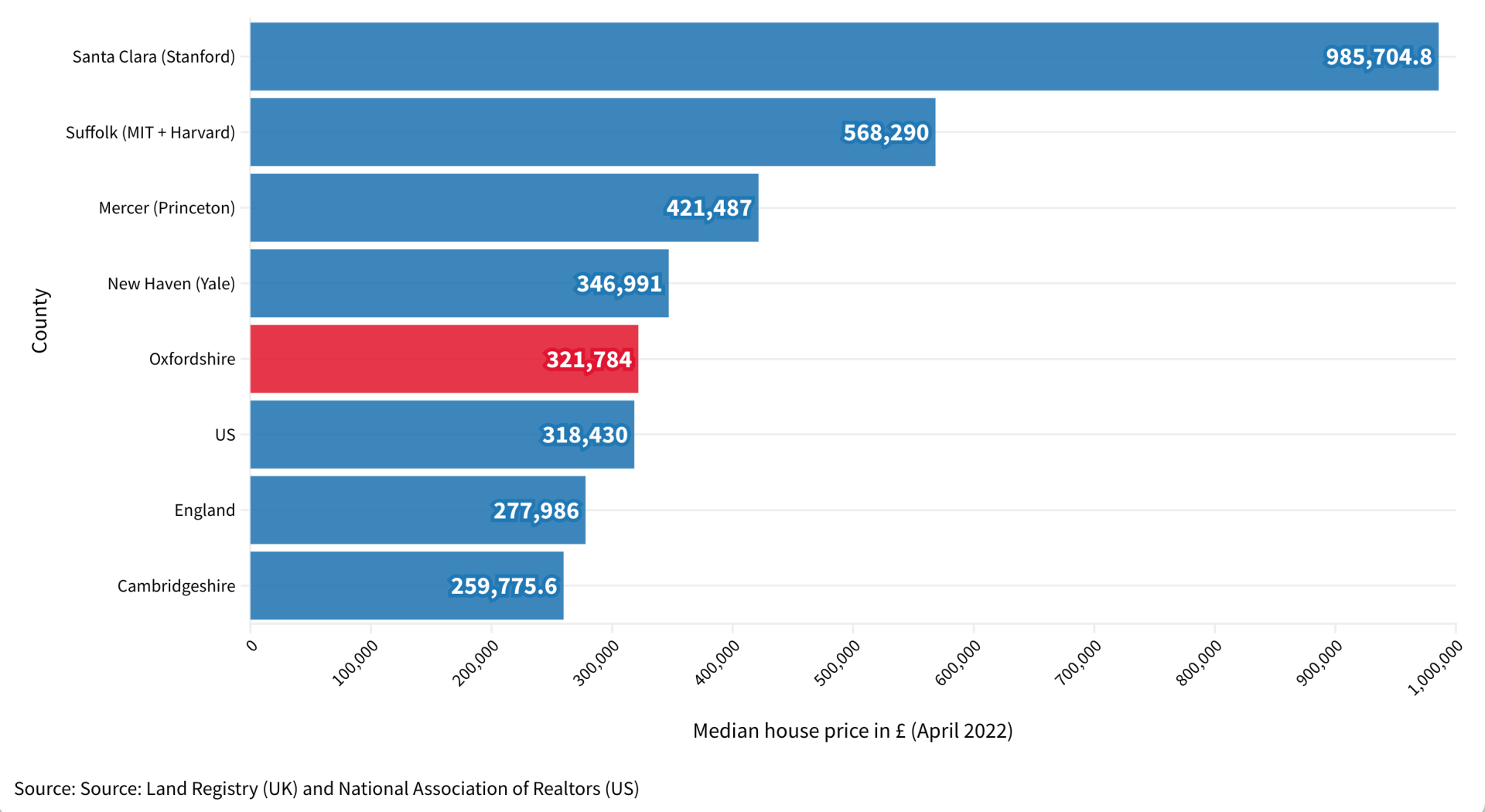

Rent is high across university towns. An analysis of rents in counties with elite universities in the UK and the US (Princeton, Harvard, Yale, MIT, Stanford, Oxford and Cambridge) puts both Oxfordshire and Cambridgeshire on the cheaper end of the scale. As of April 2022, the median monthly rent for a studio apartment in both counties was £550, a far cry from the £1630.2 needed to live in a similar sized apartment in Santa Clara County, home to Stanford University. However, larger two-bedroom apartments in Oxford are more expensive than Cambridge and close to the price found in those around Yale University in New Haven. In terms of house prices, Cambridgeshire is the cheapest amongst these counties. Next lowest is Oxfordshire, where the median house costs £62008.40 more than Cambridgeshire. Nevertheless, homes near these British universities are cheaper than homes near American universities.

When contextualised within their respective country’s housing markets though, Oxford does not appear as comparatively cheap. The rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Oxfordshire is about 41.7% higher than the English median, while rents in Mercer County (Princeton University), and New Haven, are 27% and 13.2% above the US national average respectively. Home prices in Oxford are 15.8% above the UK average, not as great an aberration as those found in Santa Clara that average about 210% higher than the US average, but still greater than a New Haven home which is 10% above the national average.

That Oxford is so expensive by UK standards distinguishes it from a handful of other elite universities. But, even those institutions located in areas where rents are more than double the national average are able to remain more affordable to staff because of the housing assistance universities offer.

Other universities offer assistance to offset cost of housing

The near-absence of housing assistance policies in Oxford places the university squarely behind its world-class peers. It does have a portfolio of university-owned rental properties, but it offers no university-wide home purchase or rental benefit. Some colleges provide joint equity purchase schemes and offer some short-term rental accommodation, particularly to graduate students, although this system seems starkly underdeveloped compared to other elite universities. Stanford, by contrast, offers five different loan programs to academics and has numerous rental options available for postgraduates and beyond.

Lack of support should be not viewed as an intrinsically British phenomenon. Many London universities offer generous relocation allowances. UCL even offers home loans up to £50,000 for certain eligible staff members.

That being said, Palo Alto and London are extremely expensive housing markets, so it should be expected that a degree of assistance is offered to attract and retain talent. However, even cheaper areas like Princeton and New Haven offer far more housing assistance than Oxford. In Princeton, the average home price is about 5.2 times the base academic staff salary average and at Yale it is 4.5 times. At Oxford, an employee occupying the lowest strand in a full-time academic position could expect to pay a bit higher, 6.4 times their salary for the average home, but still these values are not vastly different. And yet, both Yale and Princeton universities have established loan and purchasing programs where the university covers parts of the cost of home purchases, through co-buying the home or payments directly to eligible staff members. These programs are not new either; Yale’s is over 28 years old.

Even Cambridge appears slightly ahead of Oxford in terms of housing assistance,having recently constructed a dedicated community of affordable housing for its staff in Eddington. Some shared apartments here have rents, including utilities, for as low as £650 a month.

The problem in Oxford

Housing prices and a lack of support from the university have combined to create the problem, but there are other deeper structural issues within the university and the town that must be addressed. First, land is at a premium in Oxford. More so than in the United States, cities like Oxford- and Cambridge- lack land open to development on their peripheries. Much of the land outside of the current urban core area is protected, part of the “Green Belt”. This donut-shaped area includes many scenic woods, rivers and floodplains, as well as important farmland. However, it also encompasses motorways and open land, which despite not being of particular natural significance are still under restrictive regulation. Consequently, new outward development is often difficult around Oxford.

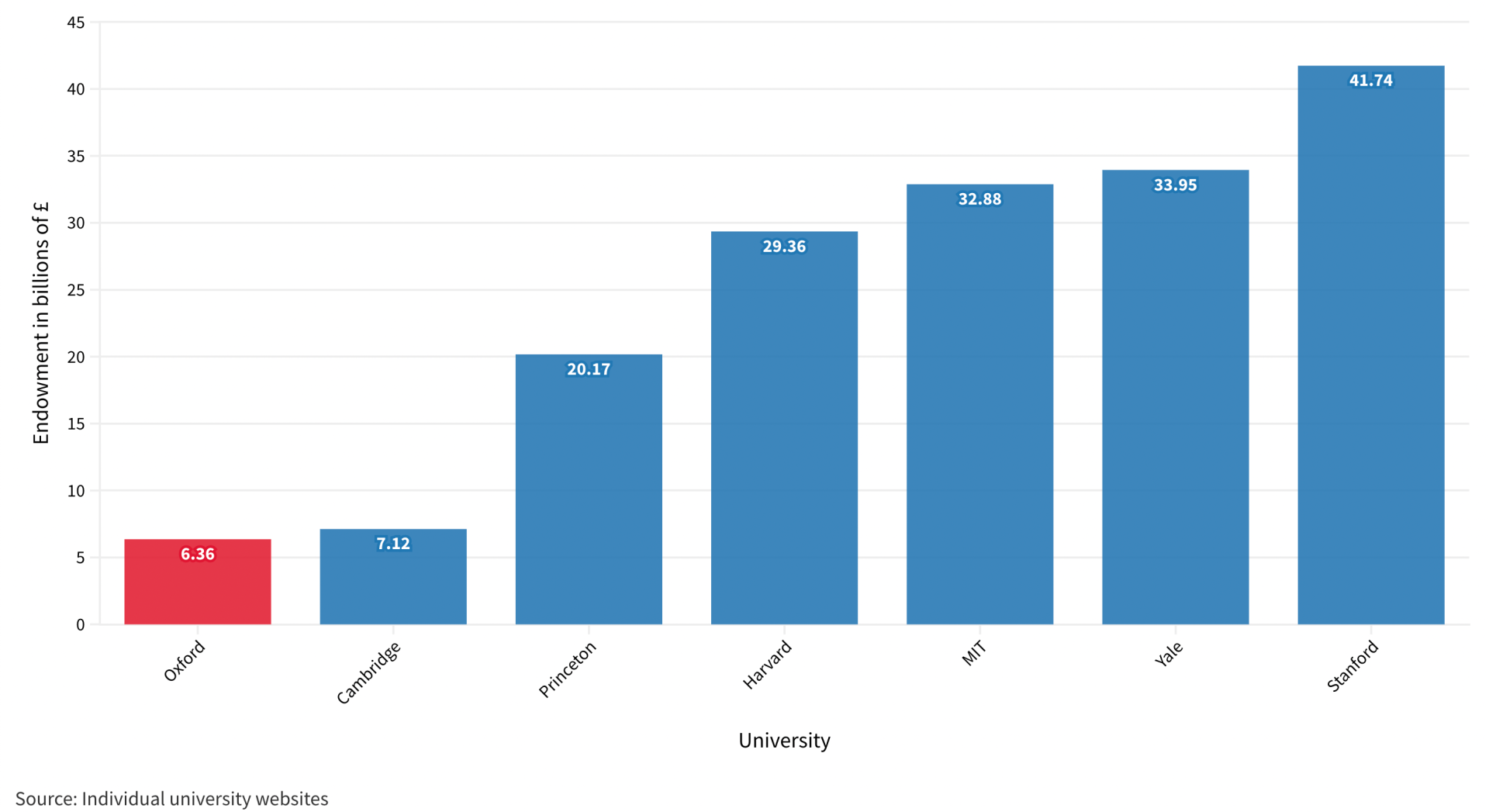

And then, there is the question of endowment. Its endowment of over six billion pounds would place it twenty-fifth in the US, about fifteen billion pounds lower than Princeton, the next poorest university examined in this article. It is lower than Cambridge’s as well, by around one billion pounds. This lack of funds is longstanding and is one of Oxford’s greatest weaknesses, partially inherent to the structure of the university itself. Each college has their own endowment, strategies for growing said endowment and fundraising departments. Furthermore, American universities generally have a greater history of alumni philanthropy, with some Ivies like Princeton boasting close to 50% alumni donation rates. “Old Members” give generously at Oxford, but not to the same extent as in the US with donations split amongst college and university initiatives.

While a large endowment does not simply enable a university to spend vast amounts of money on whatever projects need attention, it does offer flexibility. A smaller endowment prohibits Oxford from establishing the types of housing benefits that wealthier universities in the United States are able to provide for their staff. As well, the relative lack of funds partially contributes to some of the salary discrepancy we see between British and American institutions. Though, as the UCU argues, the university has an obligation to pay its staff more. David Chibnall, Vice President of the Oxford Branch, says “first thing that the University could do is ensure that pay and PGR [postgraduate research] stipends keep up with housing cost”.

Efforts to improve the housing crisis

Increasingly, the university is acknowledging both the lack of endowment and affordable housing. Prof Dame Louise Richardson, former Vice-Chancellor, has acknowledged Oxford’s comparative lack of funds and has included steps to increase the university’s endowment in her strategic plan.

In this strategic plan, the university has also set out a goal to construct one thousand new subsidised homes for college staff. The university has entered into a development partnership with L&G to reach this goal. Projects to date include the expansion of the Begbroke Science Park, which Current Pro Vice-Chancellor Prof. Irene Trace highlighted in her recent inauguration address. She reiterated that the university “want[s] to do more” and the Begrbroke development, currently in the planning stage, will “reduce strain on the city’s housing stock and public services”. The University and colleges have also made considerable investments in new accommodation, which Dr David Prout, Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Planning and Resources, explains has “reduced pressure on the local housing market”.

Individual college land holdings, like St. John’s property in North Oxford and Christ Church’s Bayswater Brook area are also being transformed into innovation and living spaces. In the case of St John’s Oxford North, 35% of these units will also be designated affordable housing. Alongside university and college developments, Oxford City Council is also pledging to build 1600 new affordable homes by 2026 and claim they are “on track to exceed this goal”. The Council adds that their Local Plan “allows employers to provide employees with affordable

housing on specific sites they own within the city”. Not only does this benefit university staff retention, it also frees up social rented homes.

In the past ten years, the university has also devoted resources to lessening the expense of commuting, particularly those who use sustainable modes of transportation. This allows staff to afford the cost of commuting from Oxfordshire’s less expensive outlying villages. Benefits include bike purchase loans, construction of showers in department buildings and subsidising new electric fleet vehicles. The program alone is not a solution, however, and many American universities have similar programs in conjunction with more affordable housing.

A more well- endowed future

A greater supply of housing and new programs to assist commuters will, if properly implemented, alleviate some of the cost of living and working in Oxford. These will come with a hefty price tag and are not the university’s sole priority. However, this crisis, intrinsically linked to the financial power of Oxford raises a more troubling question: can the ancient, tutorial-based university survive in the modern world?

This is not a new worry, as calls to grow both Oxford and Cambridge’s endowments, following the professional investment management model of many American universities, have been around for twenty-five years. Like alleviating the housing crisis, growing an endowment to rival the size of elite American universities however, will take decades.