The kitchen was scrubbed this morning, but Pam’s* superior runs her fingers across the kitchen walls and holds them up to the light, then says to clean the walls again. I ask Pam about the rash above her wrist and she says it’s the detergent. The scouts I speak to take the early buses into Oxford. They have grandchildren. Some have lived in this country for 35 years, others fled armed conflicts in Eastern Europe to come to the UK. Some are not permitted smoking breaks and are terrified of picking up a call from their kids abroad, fearing that superiors might see them on the phone.

Only two other British universities have equivalents of the scout system, where housekeeping has to navigate a hazardous student habitat to clean toilets and kitchens, make beds and hoover rooms, serve tea to guests over the vacation, and sometimes act as a welfare checkpoint. At other universities a rota in the kitchen determines who takes out the rubbish that week.

“Money is never enough”

Scouts (or ‘bedders’, as they are known at Cambridge) knock to collect trash and, at some colleges, enter unannounced. Many students find these awkward run-ins embarrassing or bothersome, and are quick to lash out at scouts, who didn’t make the rules. Cleaning the living space of routinely stressed students is a thankless job – and an underpaid one.

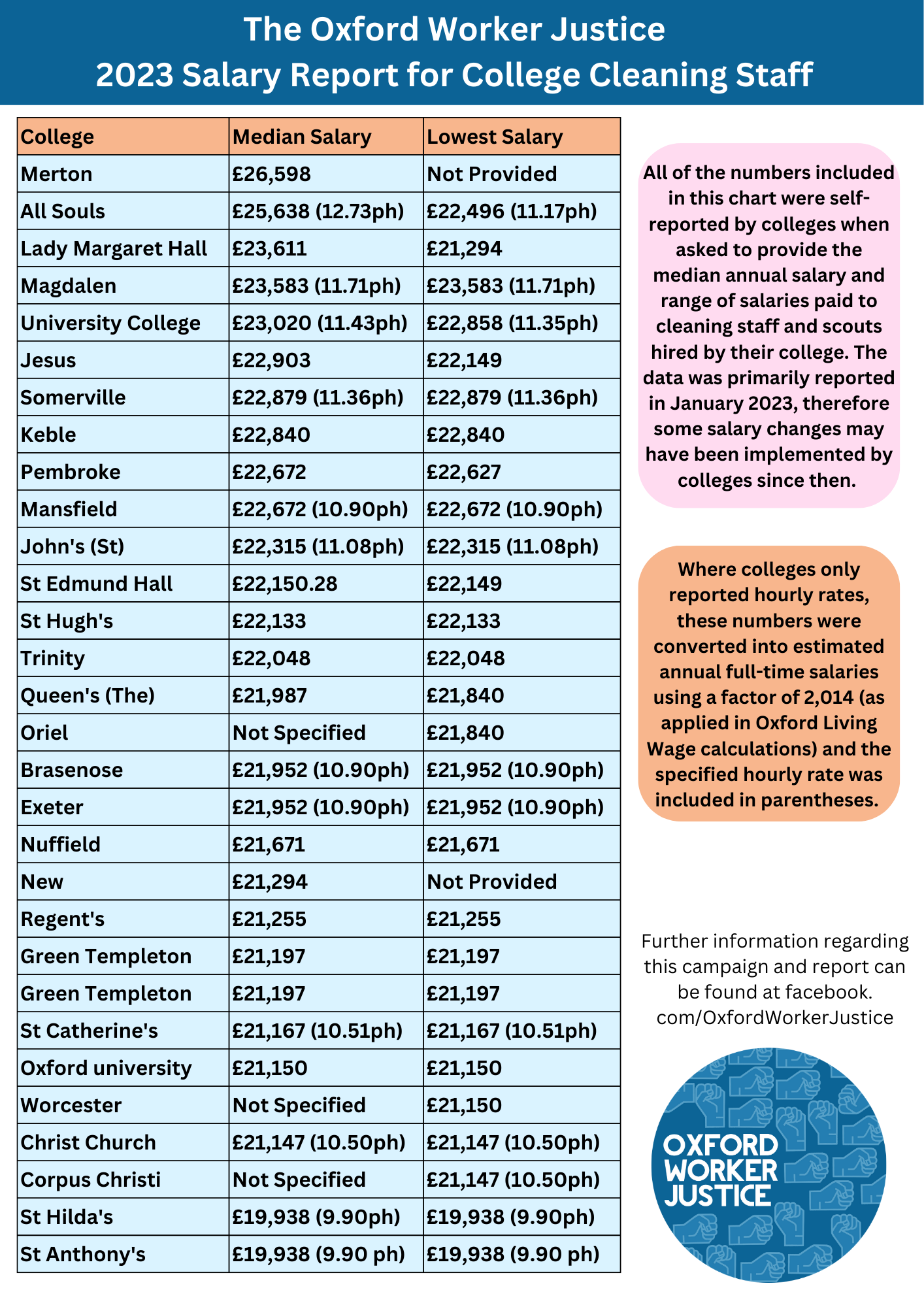

“[The] money is never enough”, Pam says to me when I ask why a 70-year-old scout with a bad knee can’t retire. Oxford Worker Justice is a student campaign that demands information from colleges about pay and other details in order to generate a ranking of colleges according to their adherence to the Oxford Living Wage (OLW). The OLW, at £10.50 at the time of inquiry earlier in the year, is a “liveable minimum pay” set by the City Council to reflect the high costs of living in Oxford. Eight colleges’ lowest wages were below the OLW and 16 colleges say they do not intend to increase wages to align with the OLW, which as of April is £11.35. Some colleges, including Christ Church and Balliol, have since told Cherwell that they will uplift salaries in line with the Oxford Living Wage this spring.

When Oxford Worker’ Justice requested information on wages in 2021, other colleges justified lower wages by saying staff had non-wage benefits like access to (public) parks or gifted chocolate at Christmas. Only ten colleges have an OLW accreditation, which is a scheme for employers to commit to pay the OLW. It should also be noted that colleges including Christ Church provide some monetary benefits for supplementary work including conference benefits.

A decentralised system

The poor pay stems in part from the prevalence of subcontractors in hiring Oxford’s scouts. Most colleges use agency staff, with Keble and LMH topping the list of most agency staff employed. This reduces administration costs and makes hiring and firing more flexible, and scouts hired through agencies often experience unique challenges. Lucy, who works with Oxford Worker Justice, says that reporting to chains of authority in both college and the agency may make for a worse work environment.

When her colleague for the building takes leave, a scout I speak to has to clean four floors instead of two without extra remuneration. There is no direct line through which to express grievances to employers as colleges are not their direct employer. Furthermore, the University does not regulate the hiring practices of colleges because colleges are “independent of the University and are independent employers”. 2021 statistics corroborate the job insecurity subcontracted workers face. Agency staff at Corpus Christi, at that time, rarely stayed in the job longer than three months. Even those who are still in a job are not guaranteed consistent work and pay, as some colleges still employ zero-hour contracts, so staff are left without work for weeks at a time.

Lucy says no college is breaking the law on the living wage, but many do not or cannot provide details on sensitive topics like whether they use agencies, or details of measures taken during the pandemic for health and safety. Oxford Worker Justice launched a petition during the pandemic in response to reports that during the lockdown college staff had to work without Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Pam experienced this and says she was terrified to have to clean the bathroom a student with COVID was using.

I ask Pam why in her years as a scout she hasn’t heard talk of unions. “They think there’s no point,” she says. Lucy from Oxford Worker Justice echoes this sentiment. She believes the college system “creates a different dynamic to other [universities] where there is one institution to put pressure on”. The lack of a centralised employer creates an insular environment so scouts have no wider channel of interaction with those at other colleges. Oxford Worker Justice used to run small groups at the now-closed East Oxford Community centre with the hope of directing workers to general unions like IWGB and UNISON that seek to represent college workers. Turnout to these meetings was, however, low.

Isolation, fear and inequality

When I reach out to friends to get them to put me in touch with their scouts, a common problem is the language barrier. At some colleges less than 30% of the staff are British. A majority of workers at St Anne’s in 2021, for example, were EU citizens. An old Cherwell investigation reported of colleges such as Jesus asking scouts to use Anglicised names, claims that were later denied by the college. I’m told that a college worker who spoke at a rally claimed that the norm of targeting immigrants for jobs emerged because they are least likely to complain, and most likely to fear the repercussions of speaking up. Lucy says it is clear that in more ways than one, “the system is designed for it to be difficult for them to ask for more … to advocate for themselves”.

Up until the 70s, scouts at Oxford were called “servants”. I am struck by anecdotes about vomit in sinks, rotting food dripping through fridges, and Lucy tells me that overwhelmingly, “scouts just wish students just didn’t do sh*tty things that make their jobs more difficult”. An article in the Telegraph by a graduate argues that “the artificial bubble of college life at Oxbridge is perhaps unlike anywhere else in the world for how it compresses privilege and poverty”. Due to language barriers, memories of bad confrontations, and a sometimes fear-fuelled work environment, scouts may find it daunting to even tell residents how hard the students make their work.

The pay gap at this world-renowned university between the yearly earnings of minimum wage workers (scouts, kitchen staff, porters, maintenance) and maximum wage employees (over £100K/year) will continue to grow if more colleges do not commit to the Oxford Living (subsistence) Wage. For scouts, Lucy suggests that “the knowledge [of better pay at other colleges] is enough to get that increase”.

Scouts want fairer pay and better treatment. The system needs reform that favours people like Pam, who tells me that all she wants is “some bl**dy respect”.

*name has been changed for anonymity

Charts created by Oxford Worker Justice

Correction 16/05/2023: Please note that the median salary Mansfield College pays for college cleaning staff is £22,672 (£10.90 ph) and the lowest hourly salary is £10.90.