Oxford’s main student publications are so ubiquitously publicised, they’re impossible to miss. The juiciest of newspapers, however, are shrouded in secrecy. Their existence is ominously revealed to first-years during Freshers’ Week, with no mention of them online and an exclusive readership.

College publications usually focus on only the life of that college (or, less charitably, its gossip). They often satirise its members which, to the unknowing eye, could seem cruel. But, these papers are overwhelmingly beloved – even by those bearing the brunt of the mockery – and are viewed as an integral part of college culture. Just what is it that keeps readers coming back for more?

To begin, New College’s The Phoenix is the most scandalous of the lot. Its copies (exclusively print) will mysteriously appear mid-term in pidges and the college bar. The Phoenix names and shames its subjects, for anything as mild as sharking to as serious as mis-spelling Atik in the freshers’ group chat. The romantic entanglements borne of the most recent bop are no longer confined to the Plush smoking area but are forever remembered in the ION (eye-on) section. Omnipresent spies observe rowing mishaps and housemate drama, JCR elections and crewdate sconces left to be recorded for posterity by the authors’ scathing pens.

Other colleges tone down the mockery or omit the gossip sections altogether, but the large majority have at least one section, mostly respecting anonymity, devoted to humorous comment on college affairs. Worcester’s Woosta Source, Lincoln’s The Imp and other more serious-looking publications still devote some space to humorous commentary of college pets’ antics or JCR meeting fiascos. The Oxymoron takes it one step further, devoting its entire publication to satire and humour centred on Oxford life.

The mockery flirts with insult but never crosses the line to meanness, however, and is clearly affectionate in even its most cutting forms. Even tales about mild JCR embezzlement, blatant Freshers’ rep sharking, and one girl’s (actually successful) quest to get with every member of a bloodline don’t make The Phoenix any real enemies. Phoenix editors ask college members before each edition if anyone would like to be omitted from it or consulted before print, but according to former editor Lewis Fisher, only about 30 people opt for this each time, less than a tenth of the college’s undergraduates. The Phoenix is almost universally beloved by the college, and gets generous funding from the JCR each term. Perhaps this is only because the Oxford college system, with insular communities in enclosed spaces and a work-hard, play-hard attitude, is the perfect breeding ground for gossip, and people are eager to sink their teeth into the new batch of information on the various embarrassing shenanigans of their fellow students.

But gossip proves time and time again to be a means of bonding. This is especially the case in larger colleges whose “college spirit” might wane; gossip magazines become a way to foster college unity and bring people closer together. Contents of gossip magazines become topics of conversations at college bars and bops, the communal embarrassment of being called out on the college paper (or relief at being left out) makes it easier to strike up conversation and connect with other college members.

This sense of camaraderie appears in many of Oxford’s silliest traditions: “shoeys”, sconcing and Oxfess likewise use embarrassment, mockery, and gossip to bring students, from sports teams to lecture halls, closer together. Sharing one common joke, or collectively poking fun at a well-known institution or person can actually be a good thing.

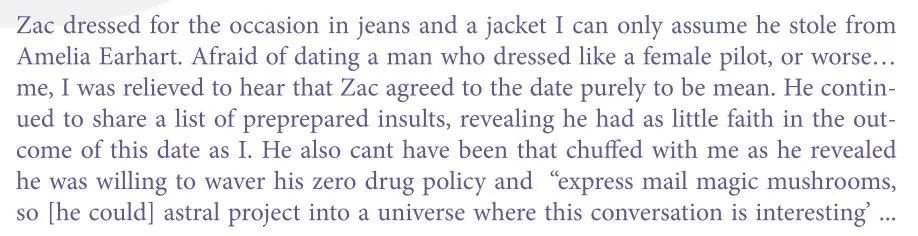

Trinity’s termly online magazine, The Broadsheet, takes self-satire to another level: there is mercy for no-one, with union hacks, finalists, and unwitting freshers all coming under the searingly funny spotlight of the authors. Articles mocking a certain prolific union member’s academic achievements or a staircase’s strange night-time activities join outrageously funny recountings of blind dates between a feminist anarchist and a clueless Etonian.

One particularly, let’s say, observant contribution to The Broadsheet records the rundown of fresher staircases. Authors “commend the wine fanatic for her humanitarian work in furthering international relations and the impressive scholarly research one classicist put into ranking every first year girl in college on looks.”

Anthropologist Robin Dunbar goes so far as to say that gossip is the human equivalent to grooming each other in that it allows individuals to maintain and strengthen their relationships: gossip enabled humanity to expand its tribes and make them more stable. Satirical college publications may serve the same function: perhaps that is why it is primarily larger colleges, where keeping up with gossip becomes impossible by first week, that have juiciest newspapers.

The apparent obsession with self-satire and mockery, however, may seem odd or even cruel to outsiders. Some say this is fitting with Oxford students’ tendency towards humour and away from taking anything seriously to save their lives. Irony and sarcasm are at the heart of Oxford humour: Oxfess’ University-wide inside jokes (Nutkins the stuffed squirrel remains a character of Oxfess, and Oxford lore to this day) are a funny part of culture and a sort of Shibboleth, immediately bringing strangers who are “in the know” closer by virtue of the shared reference. Similarly, the silly arguments between housemates or borne of the gladiatorial room ballots, chronicled in meticulous detail by The Phoenix, surely helps all involved forget any grudges and have a laugh about the absurdity of it all.

No matter the type of college publication, whether it’s an innocent chronicle of the term’s events or a scathing rundown of the College’s most scandalous happenings, it is still a crucial and beloved part of college life. The unsung heroes are the writers and editors themselves (many of whom have been incredibly helpful in the writing of this article), who by poking fun at everything and everyone, often including themselves, bring communities closer together and make Oxford life just a tad more entertaining.