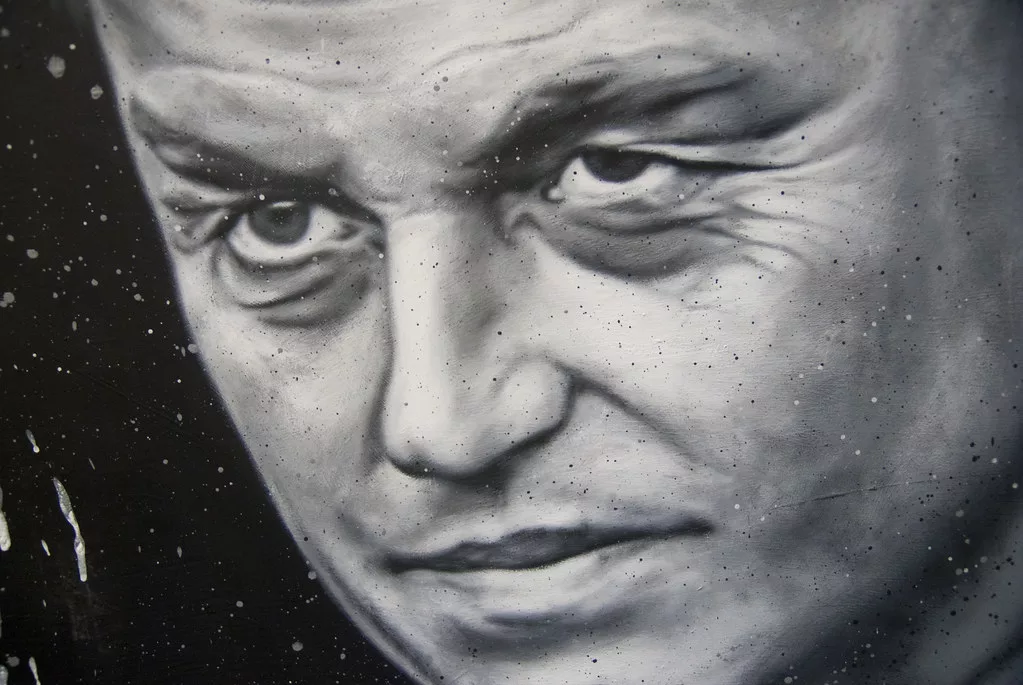

This November, Geert Wilders, the leader and founder of the Dutch far-right Party for Freedom (PVV), dominated a general election in the Netherlands. Triggered by the collapse of centrist Mark Rutte’s government, the poll saw the PVV sweep 37 seats, leaving Rutte’s incumbent conservative-liberal party, the VVD, with only 24 seats. A populist Islamophobe and ‘Nexiteer’ who has proclaimed that the “[Dutch] people must get their nation back”, Wilders’ victory is viewed by many as a nightmare scenario for the European Union. However, the Dutch coalition system means that Wilders needs 76 seats in the House of Representatives to take the reins. The question on everyone’s lips: can he make it into government?

Wilders’ main challenge is electoral arithmetic. Given that it took tentative centrist operator Rutte the best part of a year to wade through coalition talks, we cannot expect to see Wilders as Dutch prime minister any time soon. That is, if ever. 39 seats away from that coveted majority, Wilders will need the support of the centre right VVD and the Christian democratic New Social Contract (NSC); as expected, the left-wing parties have ruled out any prospect of cooperation. On top of this, now that the VVD has also dismissed a formal coalition, preferring only an informal case-by-case agreement, the odds for a majority are not on his side. More likely is a chaotic minority government that would be destabilising for both the Dutch people and at a wider European level.

A possible alternative – and by far the best-case scenario for the pro-European centre – is a broad-church coalition led by the party with the second most seats. This would be the Green/Labour left working in collaboration with the VVD and the other moderate parties. However, this will only be a live option once Wilders has definitively exhausted all potential arrangements. We’ve also got to consider this electoral sticking plaster – the narrowest of all-but-the-far-right coalitions – which would only contribute to the growing sense of political apathy as it would be nearly impossible for such a government to agree to radical change for anything at all.

The biggest worry for Ursula von der Leyen and Brussels is that Wilders’ success (albeit tempered by difficult coalition talks) seems to form part of a wider picture of growing Euroscepticism and isolationism across Europe. In Germany, amid growing dissatisfaction with the Scholz administration and protests by the country’s farmers, the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) are enjoying a poll bounce. In France, Emmanuel Macron’s desperate efforts to shore up support against a resurgent Marine le Pen include hiring a new Prime Minister, Gabriel Attal. Italy, Finland, and Sweden now all have government whose coalitions rely on the support of far-right parties. European unity – and with it solidarity with Ukraine – is running out of supporters.

The biggest concern of all still lies ahead. It comes from the EU elections in June this year, whose opinion polling does not make for happy reading for pro-Europeans. Recent polls put the far-right Identity and Democracy group third behind the major centre-right and centre-left groupings, with their highest seat share ever. Parties belonging to soft or hard Eurosceptic groups are expected to gain the most seats in Austria, Estonia, France, Hungary, Italy, and of course the Netherlands. Many of these parties whom have close ties with Putin, are critical of EU funding benchmarks that insist on protections for the rule of law, and have leaders compared to Donald Trump in their own respective countries.

It is clear that too many of these voices at the EU decision table could become catastrophic for European unity, tolerance, diversity, and cross-continent solidarity. Ukraine may have its eye on the US presidential elections this year, but it should also be wary of the consequences of the European elections as unequivocal support for military aid and sanctions against Russia is slowly chipped away. But, we can’t deny this diminishing support is not universal for two reasons.

Firstly, there are cases where the far-right has been defeated by more moderate forces. For example, this summer we saw the failure of the Vox party in Spain, as well as Donald Tusk’s election as Polish prime minister where he defeated the right-wing nationalist Law and Justice party and specifically campaigned against democratic backsliding and populist rhetoric. Something that many other centrist parties fail to do, instead trying – and failing – to mimic tough talk on immigration and national values.

Secondly, where the far-right does govern, the EU can take some relief from instances where it steps back from its more extreme policy platform to become more palatable to citizens, coalition partners, and neighbouring countries. This is epitomised by Italy’s Giorgia Meloni, whose policies towards the EU and Ukrainian military support have much more cooperative than initially feared. Wilders began his journey down the same road during the election campaign, where he reversed proposals to ban mosques and the Qur’an and toned-down talk of a potential ‘Nexit’ which he ardently called for following Britain’s departure from the EU in 2016. This simply cannot be an acceptable state of affairs. The EU will continue to fracture if it simply regards continuing to exist and continuing to send weapons to Ukraine as a job well done. A more positive vision is required.

While many of Europe’s new far-right decision-makers will dance to the EU’s tune on membership and support for Ukraine, progressives and liberals in Brussels cannot breathe a sigh of relief yet. These parties will continue to stymie progress in climate change, kindle culture wars at home against immigrants and LGBTQ+ people, and neglect the plight of those suffering most around the world. As recently as November, Wilders said that the people of Palestine should be moved to Jordan and that his government “will stop the hysterical reduction of CO2”. European liberals, be warned.