In the common room of the Taylor Institute Library, a framed row of historical engravings depict scenes of Oxford. Among them is an engraving by J. H. Parker, dated 1849, capturing a moment of “The View of the Martyr’s Memorial and Aisle”. The Martyr’s Memorial, which still stands today on St. Giles, overlooks pedestrians with parasols and scholar’s robes. On its steps two men watch another play with a dog. As I exit the library, it strikes me that in its memorials of people long deceased and its unchanging historical landscape, Oxford seems often at a standstill.

Martyr’s Memorial was erected in 1843 in remembrance of three Protestants who were burned at the stake in 1555. The buildings that Parker depicted surrounding the memorial can be observed today: St. Mary Magdalen church, the facade of Balliol College, and the buildings of Magdalen Street. Perhaps the largest discrepancy between the scene from 1849 to today is the layout of the road. While people leisurely stroll along St. Giles in the fading inked landscape, I am on the lookout for cars as I cross onto a median strip under construction, in an attempt to recapture the perspective of Parker.

Observing the memorial framed by green netting, I am reminded that despite Oxford’s seeming timelessness, things are still subject to change. Memory of a place is constantly reformulated, physically through construction and through the ways in which people remember them. Restorative works to the Martyr’s Memorial were done throughout the 20th century, and more recently, in 2002. The bright paint one can observe on the shields is thus not the same used in the 19th century, an imposition of modernity that has also affected the traditions of Oxford— such as the wearing of robes and Latin ceremonies— which have faded to moments of re-enactment in formal halls and academic ceremonies.

At the same time, these slivers of tradition also build new meanings of memorialization. As the men sit on the memorial in Parker’s engraving, on the steps one young woman now takes a lunch break while a man gazes out at the street contemplative. I overhear the conversation of three friends, one of them seemingly a local touring his companions. Throughout the years, millions of tourists have interacted with the memorial in the same way. In the Bodleian I find a 1938 guidebook to Oxford titled “The City of Spires”. In the guidebook’s first few pages a photo of the memorial advertises a local “Private Hotel”, which no longer exists, on 13-17 Magdalen street.

The dubbing of Oxford as “The City of Dreaming Spires” is a popular one that reproduces the coinage of the city as ‘that sweet city with her dreaming spires’ by Matthew Arnold in his 1865 poem Thyrsis (1865). Thyrsis commemorates Arnold’s deceased friend Arthur Hugh Clough, and opens with an exclamation of how Oxford has changed since they walked the streets together as students (‘How changed is here each spot man makes or fills!’). Perhaps the pair, then members of Balliol College, too sat on the steps of Martyr’s Memorial.

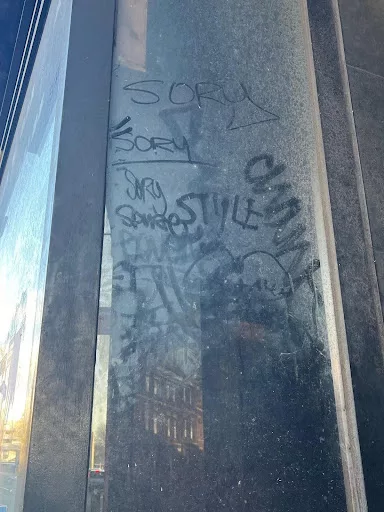

Why do we memorialise? Why are some places of memory preserved more than others (why are the ancient spires still standing, while 13-17 Magdalen Street constantly changes)? As I reflected upon this Oxford spire entrenched with memory, I noticed a graffitied wall on one of the shops flanking Martyr’s Memorial. Among the scrawl of letters one struck my eye: SPIRE. Walking through the city, I start noticing its frequency, repetitively hidden in plain sight on walls and doors, and even on a dusty window of a closed establishment.

I ran my finger through the dust, creating a streak that joins the graffiti tags. In doing so I realised that with the rain and wind these words will disappear in days. These SPIREs, unlike the towers that celebrate Oxford’s traditions of academic prestige, will be removed— if not by the elements, by local authorities. Yet, although these graffiti spires are more ephemeral than their architectural counterparts, they are similarly repeated across the city. I wonder if the creators of these spires shared a common uncertainty of when their creations will be destroyed or reconstructed.

Perhaps we create art and memorials to mark a moment that will inevitably mutate and be forgotten through time. The engraving hung on the wall of the Taylor Institute Library’s common room. Arnold’s commemoration of walks through Oxford with his best friend. The graffiti spires on the ground level of Oxford’s streets that mirror the ones that define its skyscape. Martyr’s Memorial, which does hold the same cultural weight it did when it was completed in 1843. Yet, the spire reminds one not only of the moment of religious history it remembers, but multiple memories layered with everyday repeated moments of tradition through the centuries.