Welcome back to the crash course in British politics. This column is for students who know little about British politics and want to know more. But, I firmly believe that even a seasoned observer of Westminster (the area of London with the Houses of Parliament and many government buildings) could benefit from a refresher of the basics. This week’s article will explain how British elections work, and hopefully will answer all your related questions.

Before we discuss elections, we should have a basic understanding of the British political system. The United Kingdom is a democracy with several branches of government: the executive (government), the legislative (Parliament), and the judiciary (courts). British Parliament is made up of the House of Commons, which holds 650 seats, and the House of Lords, whose members are appointed. The seats in the House of Commons represent the 650 districts in the United Kingdom, out of which 533 are in England, 59 in Scotland, 40 in Wales, and 18 in Northern Ireland. On average, each member of Parliament (MP) represents approximately 100,000 people.

Elections in the United Kingdom generally happen every five years, unless parliament is dissolved earlier (the past five British elections were: December 2019, June 2017, May 2015, May 2010, May 2005). The current Parliament first convened on December 17, 2019, which means it will dissolve at the latest on December 17, 2024 (and elections would happen approximately a month after that). Essentially, the decision on when to dissolve Parliament and hold the elections awaits Prime Minister Sunak. But, for all we know he might have already made it. These decisions depend on complex political calculations, and in Sunak’s case, a fair share of hope things will turn around for the Conservative Party.

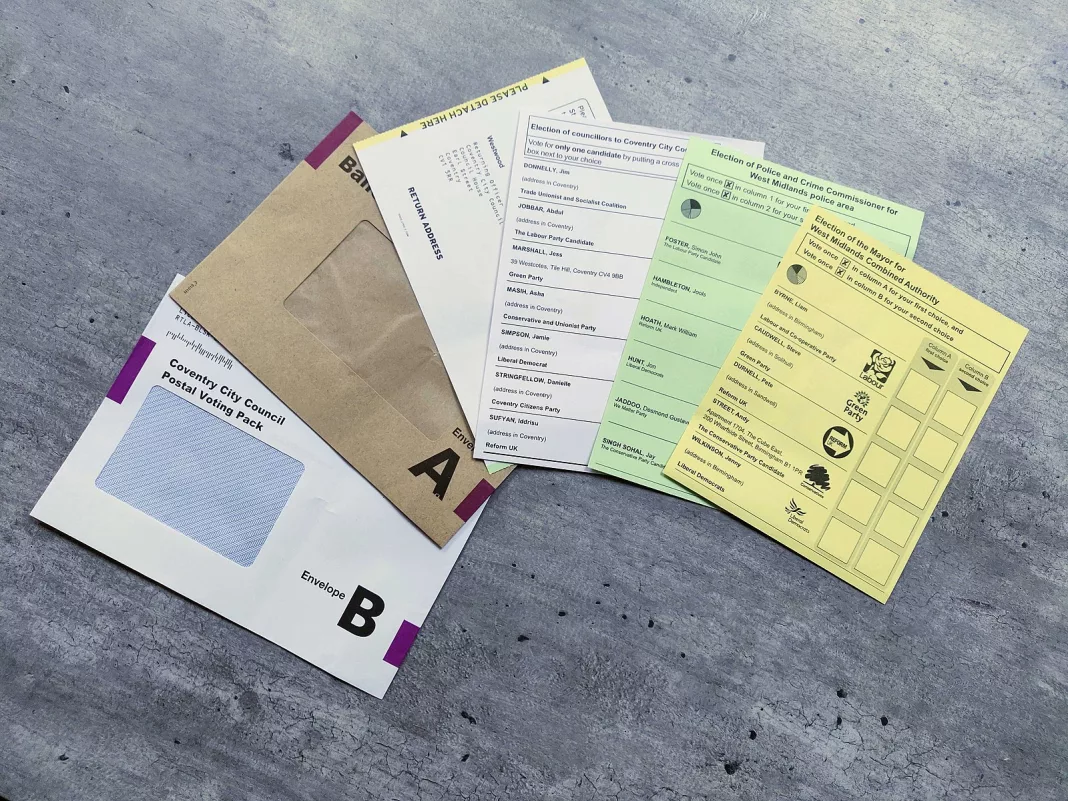

When elections finally happen every British citizen over 18 will have a chance to choose the ballot box – but what will they choose? In the United Kingdom, every citizen votes for a member of Parliament who will represent their district at the House of Commons (and not directly for the Prime Minister). These members of Parliament run on behalf of parties, and essentially are the party’s representatives for each district; the party that wins the most districts, and accordingly the most seats in Parliament will create the government. The winning party’s leader – today, realistically, either Rishi Sunak (Conservative) or Keir Starmer (Labour) – will become the Prime Minister.

In recent elections, two important changes occurred compared with historical trends. First, small parties (Scottish National Party, the Liberal Democrats, the Democratic Unionist Party, and the Green Party) have won more seats at the expense of the big parties (Labour and the Conservative Party). This has made it more difficult for the big parties to win an absolute majority and forced them into coalitions. The second change is that the elections’ results were even closer where in 2017 we saw 11 seats were decided on less than 100 votes and a dozen more on hundreds. This means they are very difficult to predict and easily swayed.

Finally, on election day, the polls open at 7:00 and close at 22:00. The results of the exit poll are announced very soon after that. The official results will be announced once all districts declare their winners, and could arrive overnight.