Elizabeth Bishop’s poem ‘One Art’ is beautiful because of its hypocrisy. The speaker exalts loss – of places, names, houses, their mother’s watch – with an odd joviality. You’re sure, reading it for the first time, that there must be something disingenuous going on here. The act of writing exposes the chasm between speech and feeling, as Bishop squeezes out the painful final lines:

–Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

Bishop’s voice here, before she lets the mask slip, seems to be reminiscent of some stoic and ancient philosophy, that recognises the futility of attaching our worth and feelings to things you can have, whether it is a beautiful ring, or a city, or a person. She remains resistant to the hyper-consumption of modernity, when every time we open our phones, we are bombarded with an array of products that promise to make us feel a little better about ourselves if we buy them. But all of that is old news- we’ve all learned by now that ordering something off Amazon can’t replace those parts of ourselves we suspect have gone missing.

Besides, isn’t it boring, not to covet anything? A friend texted me recently with the quote that ‘in capitalist societies, to love things is something of an embarrassment’, and I felt gratified that I did have material things in my life to treasure: my books, my favourite clothes, and my diaries. Treasuring physical objects, especially ones that you have dreamed of and laboured over, feels like an apt rebellion in the age of click and collect.

Of course, there is a more pertinent theme to ‘One Art’ than possession, and that is loss. The motion of it, its substance, its stubborn revival throughout our lives. Until recently, I was fairly sure that the loss of a possession could never truly devastate me- to do so seemed frivolous, spoiled, even a little unintelligent. I could lose my favourite pair of shoes, but I would still be me, I thought. That is, until I lost my diary.

Well, it wasn’t technically lost; it was stolen on the last night of term. I always find endings uncomfortably liminal, full of fluctuating emotions and swallowed goodbyes that live in your throat for weeks. That’s exactly why this Michaelmas I strategised something that would keep me occupied and not too existential: the faithful pub trip. Bundling into the Lamb and Flag on one of the first nights of December, I chatted with a friend about the last few days, and then briefly entertained some Americans who wanted restaurant recommendations from ‘two real Oxford girls’. It was a normal evening, and the infinite potential for disaster that ‘Friday of 8th week’ holds in my mind turned out to be, well, in my mind. That is, until I woke up the morning after and realised I had left my bag in the pub. After confirming nobody had turned anything in, I began to accept that the journal, stored inside, was truly lost.

The first stage of acceptance took place in Crewe train station, which is already one of the most depressing places in England, indeed only made more so by the sight of me wailing on the phone to my mother as I wandered aimlessly up and down a platform. The shock of receiving the message that, ‘No, no brown leather bag was handed in last night’, had sent me into a temporary frenzy, and I was sobbing unashamedly in public for the first time of my adult life. My mum has watched me grow into a person who cocoons herself with words. Closest to my heart is the dear-diary prose of the journal, the mode of writing I began with at age five, which I still swear by now. At twenty, the form of the diary is still sacred to me, the place where I express what I am and craft the person I hope to be.

The notebook I lost spanned around six months of my life, including all my summer travels, even a few photos. But it wasn’t necessarily the memories I had recorded that hurt the most to lose- it was my feelings. My most private, most painful, and sometimes most shameful thoughts went into that notebook, the most previous entry dated only a few days prior to its loss. The thought tormented me, of a complete stranger rifling through the pages I had imprinted my heart onto. Would they be amused? Would they think I was silly, or reprehensible? My worst fear was that they would view it as entertainment, an opportunity to tour my mind as a burglar would stroll into an unlocked house. ‘I’m sure you feel as if you’ve been violated,’ my mum said over the phone when I had stopped crying. Her words twisted in my stomach, but I was grateful that at least she understood.

When I arrived home for Christmas, I was drawn to the keepsake box stowed under my bed which contains all the diaries I have finished. My grief had subsided after a week, but I found myself thinking about writing more than I was actually writing. Why, I asked myself, had this habit endured for so much of my life, long enough to become instinct? Why did life not feel entirely real until I had written it down? Was it possible, I thought, that I had relied too much on these diaries to make my reality?

Diving headfirst into existentialism, I pulled out the first notebook from the box. A gift from my aunt when I was five, it came with a little lock and key that I quickly lost, but the notebook remains. It’s as battered as you would expect: some pages are ripped out, some just contain scribbles, or a person without arms I had abandoned drawing when something more interesting came along. Progressing through earlier journals acquainted me with the mechanics of writing- how to avoid smudging ink, how to date, how to write in cursive. When I was six or seven, I began to chronologise, and increasingly to complain- about my annoying sister, or someone at school.

There’s little variety. I myself don’t find them that interesting, despite having actually written them. Nevertheless, I can appreciate them for what they represent; namely, the beginning of my discovery of a secret place I could reside. A place of my own creation, which both did and did not exist, which was everywhere but only for me to find- in short, privacy.

Childhood is not a time many would define by privacy. For a start, you are taken care of for most of it, watched by someone, whether it be a parent or teacher. Sharing a bedroom meant I hardly had any time alone until I was around ten- but a diary in childhood is one of the few places of solitude you can create for yourself. I was a quiet and at times strangely introspective kid, and I quickly learned that reading or writing meant people would leave me alone, and that being alone entailed a different kind of living than I had experienced before.

Also apparent from my writing is how expert the young diarist can become at mimicry; at age eight I strolled into a narrative voice heavily influenced by Diary of a Wimpy Kid, and I even accompanied my entries with drawings for a few weeks. Thankfully I gave that up quickly after realising whatever talents I possessed did not lie in visual art. At age ten, when I was writing in a red fabric-bound journal, I faithfully addressed it as ‘kitty’, hoping to emulate my new personal hero, Anne Frank. Beyond the diarists and diary-novels I was reading at the time, these entries are really an unconscious reflection of what I loved to read when I learned to love reading, from The Little Princess to The Hunger Games.

In May 2017, I picked up my journal to write an inventory of all my friends at school; what I liked and disliked about them, who was popular, who I admired and who I was jealous of. The teenage diarist is one of the most enduring images in pop culture; creative, disdainful and rebellious, the diary is an adolescent’s new playground. It’s clear I was revelling in the true range of my emotions when I was fourteen: one paragraph I’m dissecting the reasons for my parent’s divorce with surprising maturity, the next I’m describing the specific colour of my period blood. At this age I discovered how liberating it can be to simply write the unspeakable, something you would have never dared to articulate before that now exists just for you.

At seventeen, Sylvia Plath’s collected diaries became my bible. I loved the passion she observed the world with, and tried to channel her diligent diarising into my own, fervently recording interactions I had with people in coffee shops and attempting to get down scraps of poetry. Now that I’m a few years older, and one stolen diary wiser, I can’t help but think of the trespass it is to treasure someone’s personal writings that were never intended for publication- that possibly would never have been in the public domain if their author had not committed suicide. But I fell in love with Plath’s writing about fish and chips before I was mature enough to consider the ethics of reading it-

‘The girl picked up the cracked metal tin of salt and snowed it into the bag. Then, taking the cut-glass bottle of vinegar, she showered it onto the fish, lifted the edge of it, and doused the potatoes. She handed the bag back to the woman, who wrapped it in a sheaf of newspaper.’

Today I still find it difficult, as a literature student, to know what I think about reading diaries as literary artefacts. The private self is indeed different from the self we construct to face the public; but it is still constructed nonetheless, and whether it is ‘truer’ I could not say. Apart from the fact that, if the stranger that stole my diary reads it instead of throwing it in the bin, I hope they would understand that although that notebook expresses important parts of myself, it hardly constitutes the whole of it.

When I was eighteen I started university and stopped writing for myself. At the same time I was writing more than I ever had in my life, and became quickly acquainted with the rhythm of churning out the weekly essay. People often don’t have the energy to write anything but their tutorial essays at Oxford, and this was true for me, but the bigger obstacle to my keeping a diary was actually the new version of my life I was struggling to become acquainted with. As I departed from adolescence, so I departed from the ways I wrote about my adolescence, and after many failed attempts at describing my new life, I got tired of staring at blank pages and angry at myself for being unable to fill them with anything but self-pity. So I put my pen down for ten months and learned how to have fun.

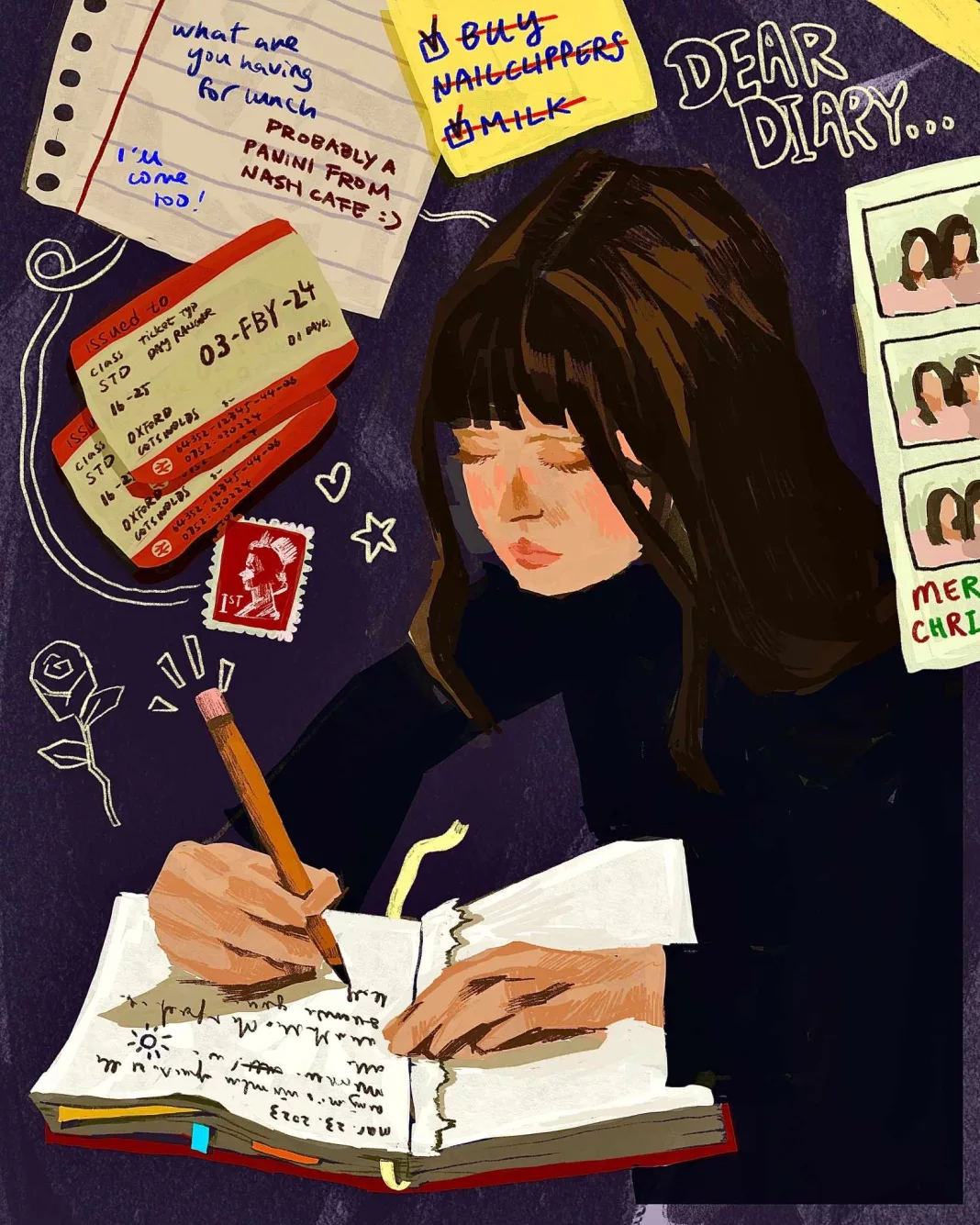

But old habits are hard to break, and in my second year I inadvertently started writing about my feelings again when I was keeping a travel itinerary in Morocco. My diaries now look very different to what they did before; they are not such obviously precious objects, with pages ripped out, scribbled over, paragraphs abruptly broken off when I had to dash out of the house, and entries interspersed with shopping lists which remind me to buy a new pair of nail scissors. I’ve also taken to obsessively collecting ticket stubs, notes from friends, play programmes, and postcards, in an attempt to scrapbook. It’s an activity that I find profoundly feminine and novel, with its roots in the 19th century scrapbooking of wealthy and travelled women. Trying it myself only sheds light on my own shortcomings, and the unrecognised talents of women living centuries ago, who were able to create such beautiful works of art in their day-to-day lives.

Diarising is one of the most socially accepted forms of vanity, a room which contains only your voice. When I lost mine, it was the loss of this privacy, the preserved parts of myself – shopping lists and all – that hurt the most to be parted from. But as the weeks have passed, I’ve forgotten most of what I wrote in the stolen notebook, and I think less and less about the anonymous thief who may be delighting in it. Most surprisingly, I’m still me, with the same ideas and feelings which I can record in my new journal (I treated myself to my first Moleskine to help me through the morning period).

I always assumed that I journaled to obtain self-discovery; that one day I might stumble across the clearly articulated source of all my problems in an entry dated ten years prior. How naïve it was, I realise now, to think I could be my own archivist. Writing about my life could never solve the question of who I am; that kind of work must be done away from the page. What I have learned is that these notebooks are aesthetic testimonies to the various chapters of my life. The greatest joy of keeping them is being able to flick through the filled pages and basking in the texture of my own existence: ‘I am, I am, I am.’

When I lost my journal, I was confronted with how much of a hoarder I am, of my emotions as much as my possessions. What I failed to realise before is that all diary keeping is loss. What’s present in my entries is the shedding of pain and worries, hopes and aspirations, so that I can move through life a little less encumbered by their weight. It is an endless labour of love that involves parting with my feelings in the hope that they can find a more bearable form in language. It demands me to trust that I have the ability to make something useful out of this separation.

Diaries are collections of our most noteworthy debris, and we keep them because, as long as they have blank pages to offer, they, in turn, offer the opportunity to lose whatever is causing weight on the mind and heart: an exercise in self-annihilation as much as self-creation. It took a forgotten bag and a healthy dose of thievery for me to realise this, and to know that Elizabeth Bishop is right after all; loss is an art, and I have been unwittingly practising it since the Christmas I received my first notebook. Once I got past the sensation of feeling as though I had lost a limb, I welcomed my diary’s disappearance as an opportunity to let go: of the feelings of inadequacy and guilt it sometimes stored, of unkind words about the people I love, of unfulfilled wishes.

Of course, I could have taken a different route of cynicism and anger, that I can never keep the things I treasure safe. But so much writing has taught me that I do have free will in small matters such as these, so I’ve chosen to be kind to myself, to craft a story and a lesson out of the whole affair. Isn’t it what I’ve been preparing for all along?