「今度は今度。今は今。」(“Next time is next time. Now is now.”)

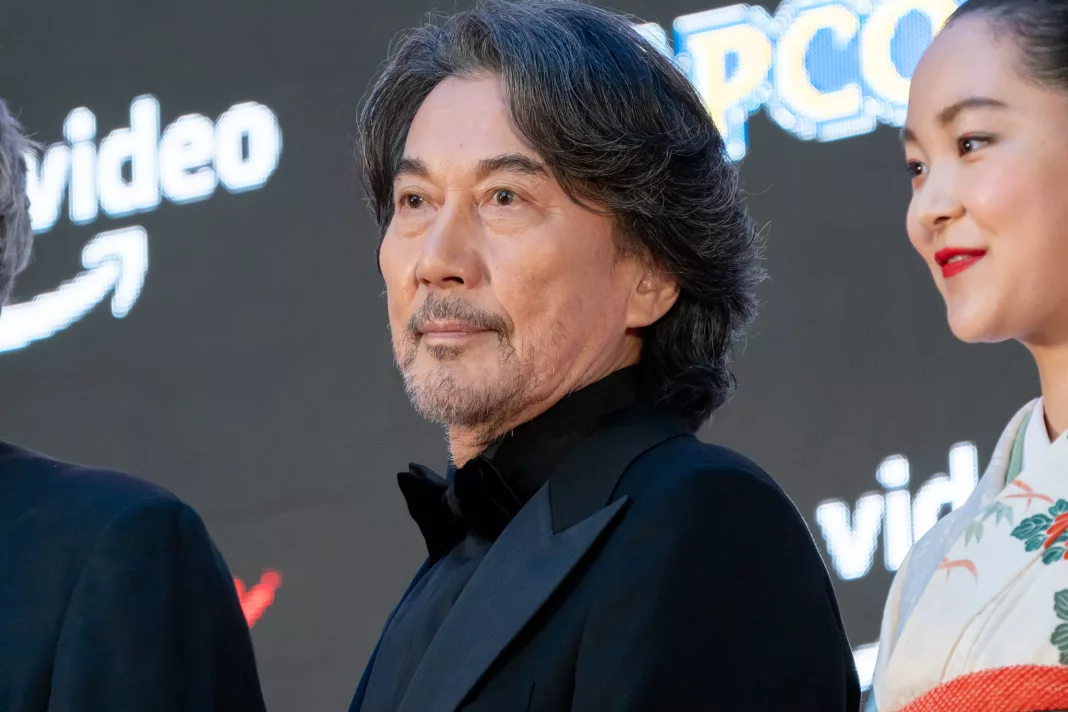

So tells Hirayama (a masterful Koji Yakusho), the central character in Japanese-language film Perfect Days, to his runaway niece, Niko (Arisa Nakano), when he tells her that he won’t take her to the sea that day. But this phrase could just as well summarise the film itself; I don’t think I’ve ever felt so ‘in the moment’ while watching a film as I did with Perfect Days, with its documentary-style handheld shots and meditative pace. Far from worrying about the past or the future within a conventional plot, Perfect Days provides us with a rare opportunity to see the world through the eyes of someone who lives each day ‘as if it were an entire life’.

Directed by German director Wim Wenders, Perfect Days follows twelve days in the life of Hirayama, a cleaner of the architecturally striking and often high-tech public toilets in present-day Tokyo. Hirayama seems highly content with his solitary and minimalist daily routine, which he has followed for years. Waking up at dawn in a suburb by the Tokyo Skytree, he drives his blue Daihatsu minivan to work in Shibuya, takes pictures of trees in a park with his 35mm Olympus film camera, goes to the same bar in Asakusa subway station for dinner, and reads a book from the local second-hand bookstore – we see him reading Patricia Highsmith, William Faulkner and Aya Kōda – before going to sleep. While the film may initially seem repetitive, over time, it becomes clear that despite this apparently rigid routine, no two days in Hirayama’s life are the same; in fact, over these twelve days, we see the character experience the ultimate emotional highs and lows.

Hirayama is a man of few words, whose feelings and personality we come to understand partly through his choice of music: soft rock hits from the 60s and 70s (think Lou Reed, The Animals or Otis Redding), which he plays from cassette tapes during his drives to and from work. However, despite the relative lack of dialogue in the film, Yakusho manages to communicate, through just a single glance or change in facial expression, the profound empathy and tenderness of his character, as well as the possible pain in his past from which he may be shielding himself. This is particularly true in the final scene, when Hirayama is shown driving to Nina Simone’s Feeling Good (“It’s a new dawn / It’s a new day / It’s a new life”), with his expression rapidly switching between joy and sorrow, in what is perhaps the most impressive display of Yakusho’s acting in the whole film.

Perfect Days captures the joyful, humorous and poignant moments in Hirayama’s everyday interactions with people from all walks of life, from his lovelorn co-worker, Takashi (an almost caricaturish Tokio Emoto), to the hostess of the izakaya he frequents, Mama (Sayuri Ishikawa), to a homeless man (Min Tanaka) who is treated as invisible by everyone else around him. Although many of the comedic moments feel somewhat exaggerated – for instance, when Hirayama dashes down the staircase in his apartment to avoid being in front of Niko while she gets dressed – there are also some genuine laugh-out-loud moments, the chief one being when Takashi’s love interest Aya (a beguiling Aoi Yamada), who seems more interested in Hirayama’s cassette collection than in Takashi, says goodbye to a startled Hirayama with a kiss on the cheek.

Despite its generally whimsical tone, Perfect Days does not shy away from exploring darker themes, such as when Niko makes an off-hand remark to Hirayama that she “might end up like Victor”, the young boy in Highsmith’s short story Terrapin who is driven to murder his emotionally abusive mother, and also in the devastating climax, where Hirayama is confronted with the unbridgeable divide that has been created between him and another key character.

Franz Lustig’s precise cinematography greatly contributes to our understanding of Hirayama as a character: in one scene, the camera wordlessly scans across Hirayama’s large book collection in his otherwise austere apartment, prompting the audience to wonder whether there was ever more to Hirayama’s life than his current existence as a toilet cleaner. As someone who has spent a considerable amount of time in Japan, I also found the film’s visuals and soundscape thoroughly convincing: from hearing the ringing of the closing railway barriers signalling the incoming approach of a train, to glimpsing the red paper bag of renowned confectioner Kamakura Beniya, to sensing the palpable excitement in a bar as a Yomiuri Giants baseball game is broadcast, watching Perfect Days made me feel entirely transported to Tokyo.

The daytime scenes of the film are complemented by brief experimental, black-and-white dream sequences produced by Wenders’ wife, Donata Wenders, which offer glimpses into Hirayama’s subconscious; in particular, they reveal his fascination with komorebi, a Japanese concept describing the beautiful yet ephemeral way in which light filters through tree leaves, which in turn serves as a metaphor for the fleeting nature of life. While these sequences provide an intriguing addition to the otherwise realist nature of the film, this message could have been expressed more subtly: given the constant appearance of komorebi throughout the film, not just in Hirayama’s dreams but also in his everyday routine, the audience was left in no doubt about its significance from early on.

Overall, I found Perfect Days to be a bittersweet and profoundly moving film about living in the moment. While the steady pace and loose narrative of the film may not initially appeal to everyone, Yakusho’s standout performance and Lustig’s immersive cinematography make it well worth a watch.