We all need to drink more water. A 1998 New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center survey of 3003 Americans found that 75% of those interviewed were ‘chronically dehydrated’ — a condition apparently characterised by fatigue, memory loss, irritability, and anxiety. It is no wonder that, according to a Cherwell poll, 78% of Oxford students claim they are ‘trying to drink more water.’

Conventional wisdom prescribes that each person drink eight glasses (or two litres) of water a day; an amount so difficult to maintain that it has spawned countless industries bent on supporting our apparent need for endless hydration, and demanded the writing of NHS guidelines and Healthline articles on how to force ourselves to drink more. The internet is full of information on the seemingly exponential benefits of excessive hydration; according to TikTok ‘hydration experts’, drinking more water can clear your skin, heal eczema and flush toxins from your organs . Water consumption is no longer a fulfilment of the biological need of thirst, but an endeavour to be a more attractive, healthier, happier, better version of yourself.

But is this true?

I reached out to Dr. Tamara Hew-Butler, a Professor of Sports Science at Wade State University, who explained that, “most people do not need to be drinking 8 glasses of water a day. The amount of water you need to be consuming is dependent on a lot of things, like your weight or the climate you’re in. We also get a lot of our daily water and minerals from the food we eat.” When I push her on the seeming necessity of driving oneself to drink when not thirsty, she explains that “the gene for thirst is one of the oldest and best evolved in the human body. It is probably the best marker for when you need to be drinking water.” On the possibility of health benefits from drinking too much water, she explains that “it can help prevent UTIs, if you have a history of UTIs, or help prevent kidney stones, if you have a history of kidney stones. Apart from that, the only thing your body is doing with that excess water is peeing it out.”

Yet, despite this evidence, myths surrounding hydration still abound. In fact, water has long been linked both to ideals not only about health, but purity and goodness; see the ostensible healing qualities of Roman Baths, the historical folk medicine of healing wells, even the symbolic purification of baptism. As the Royal College of Physicians in Edinburgh explains, at different points of history water has been touted as a cure to “all manner of ailments – from smallpox, to gout and indigestion.” Hew–Butler traces the provenance and endurance of these ideals to the fact that water is “readily available, and necessary for life. There also aren’t any real dangers from drinking more water, unless you take it to extremes.” There is almost a common-sense element to the promotion of over-hydration — drinking enough water is crucial to health — what harm could come from drinking more?

However, it would be remiss to chalk our modern take on hydration to simple medical misconception. In truth, it is a highly profitable marketing scheme which helps to fuel some high-value industries. As Hew-Butler explains, “these commercial conceptions of ‘hydration’ are really very recent— I first noticed it in Gatorade marketing campaigns in the 90s, then with plastic bottled mineral water in the 2000s.” The academics and research of hydration are therefore saturated with the corporate interests that they support; the Cornell Medical Centre’s findings on hydration — which, as you may remember, stated that 75% of adults are chronically dehydrated — were funded by the International Bottled Water Association. Their subjects’ ostensible ‘dehydration’ was not determined by medical testing, but by, as Hew Butler outlines, asking if they ‘drank at least 8 glasses of water a day,’ and declaring them dehydrated if they did not. When I tried to find their research for myself, I first saw it linked on a website selling flavoured water supplements.

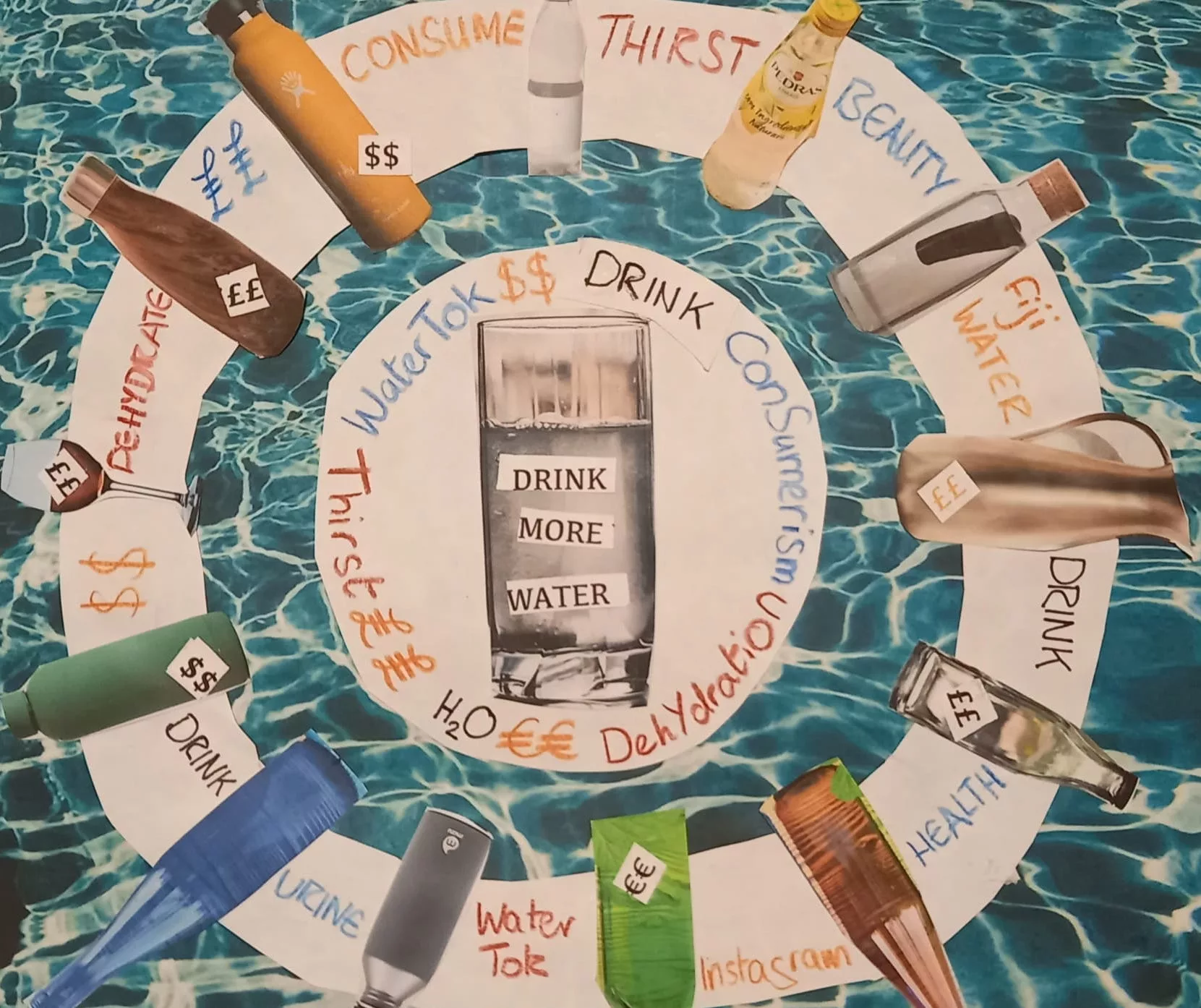

Stoking fears about dehydration translates directly into real-world profits. As of 2023, the bottled water industry was valued at £2.1 billion in the UK alone — 20 years ago, influencers photographed themselves with Fiji Water, sleekly packaged bottles of water which boasted high contents of ostensibly healthy minerals. As concerns about plastic pollution grew in the public consciousness, fueled by the release of studies finding microplastics in plastic water bottles, the commercial focus shifted towards the development and marketing of reusable water bottles. Contrary to their claims towards sustainability, these bottles arrive in noticeable trends, and develop into fashion statements of their own — you might remember the seemingly ubiquitous Chillis bottles (and ensuing knockoffs) of the later 2010s, the gallon-sized Hydromates, with their (vaguely threatening) printed encouragements of ‘KEEP DRINKING’, as endorsed by celebrities like Kendall Jenner, or the relentlessly marketed Airup bottles, which promise to flavour water (and therefore encourage its consumption) with ‘scent technology’. Of course, you would be entirely forgiven for not remembering any of these bottles; as with all trends, they have all experienced a brief craze of visibility before their inevitable, ever-swifter replacement with the next bottle on the market.

The current water bottle du jour, however, has raised a little more controversy. Priced at £45, the Stanley Quencher cup is a 1.2 litre tumblr manufactured by Stanley, a brand of previously utilitarian water bottles, which touted its products as construction site essentials. Their shift in advertising has paid off; CNBC estimates Stanley made over $750m last year, compared with an average of $70m a year before 2020. Perhaps the most useful tool in Stanley’s rebranding has been the social media zeitgeist that surrounded them. They have quickly become a mainstay of ‘WaterTok’, a TikTok subculture populated by well-hydrated (mostly) women — Stanley Cups are their weapon of choice against the spectre of dehydration. Under the #WaterTok Hashtag, you can find countless videos of its members making their ‘water of the day’, filling their cups with multiple flavouring packets and sugar-free syrups in order to produce moderately off-putting concoctions such as ‘Birthday Cake’ and ‘Mermaid’ flavoured water. Any use of flavouring is, of course, entirely justified as a means towards the ultimate end of ‘drinking more water’. WaterTok’s cultural prominence, (and therefore the ensuing backlash against it) was precipitated in early 2024 by Stanley’s collaboration with Starbucks to release a limited-edition pitcher, resulting in fatalistic and purge-style video clips of well-manicured American women tussling over the cups in outlets of Target, the American retailer. The videos were quickly followed by backlash from social and conventional media alike, of varying legitimacy. It is true that the flash-marketing and mass-collection (many WaterTokers boast huge, multi-coloured collections of Stanley Cups) of ostensibly sustainable products does undercut the environmental benefits of their production — yet the conversation around WaterTok has been (true to general internet form) one of mockery, rather than discussion.

Much of this ridicule is notably gendered. On the 28th of January 2024, the sketch show Saturday Night Live released their ‘Big Dumb Cups’ sketch, in which members of the show’s cast sport thick Southern accents, blonde wigs, vacant stares, and, of course, Stanley Cups. The Stanley Cup, therefore, seems to have grown from a simple product to a shorthand for a type of person; to mock the bottle is to mock the buyer. The surrounding discourse is, of course, entirely aware of this — one comment lauded the sketch for having “Absolutely NAILED this type of woman!”, while others discuss how they are “slaying the white mormon mom!”. Each snide aside locates the cups’ users within a distinct societal archetype, one profiled as white, lower-middle class, Christian (somehow?), and, of course, female. Mockery of the cups, therefore, manifests not only as a reaction to the consumerism they represent, but as an excuse to mock the ‘type’ of woman to whom they are attributed, an outlet for internet users to purge themselves of their (apparent) vitriol for blonde Mormon mothers of three.

When viewed through the lens of the gendered ridicule it enables, the scale of the backlash generated by the cups begins to make more sense. J. B. MacKinnon, author of The Day the World Stops Shopping: How Ending Consumerism Gives Us a Better Life and a Greener World, characterises these flurries of outrage as “finger-wagging”; the consumer frenzy surrounding Stanley Cups seems to be facing disproportionate criticism compared to its relatively insignificant impact on the environment, compared to, say, the ever-churning behemoth of Fast fashion or the massive emissions produced by commercial air travel.

It is not only the trend’s detractors who use the cups as a marker of identity; like many products peddled to consumers, they inhabit the cultural zeitgeist as more than just a water bottle, but as a declaration of values. This, of course, is not only unique to water bottles; consumption, in recent years, has equated to its own form of communication. Products have increasingly become coveted, not for what they do, but for what they mean. A friend of mine who bought a Stanley claimed she was motivated partly by seeing “so many people on socials” with them, and the hope that it would push her to do “cute aesthetic work with it.”

As far as purchases go, the cups are clearly aspirational; Hew-Butler described them as a “symbol of health”, a sign that their user is drinking their water, taking care of the environment, consuming in the marketing-approved right way. My friend largely attributed her Stanley Cup purchase to the fact that she felt it would “help [her] to drink more water”; and when water is falsely equated to health, attractiveness, and happiness, there is more to drinking more water than simply drinking more water. It is not only a reach for self-betterment, but, in the cases of cups like the Stanley, a public communication of this reach.

Hew-Butler’s summary of the over-marketing of hydration is simple; in her words, “to be told you need to drink more water is to force you into thinking that you need something that you really don’t.” Perhaps this is what is so objectionable about the overconsumption of Stanley cups — there is something bleakly metaphorical in the whole cycle of buying a bottle that you do not need to own, in order to force yourself to drink water that you do not need to drink. Certainly, when Hew-Butler explains that “people are constantly sipping, so they are never really thirsty, and so they think their thirst is ‘broken’, and they feel like they should be drinking even more,” I am struck for a moment by the utter futility of the scene she describes.

On the flip side of water’s commodification lie its consumers, for whom thirst is characterised as an endless, cavernous need. It is insatiable, even in the face of all the products sold to help sate it; you cannot quench a thirst that you do not feel, and you can never have enough of something you never really needed at all.

Artwork by Oliver Ray