The walls of the National Portrait Gallery in London are dotted with an eclectic mix of paintings and photographs. There is no hierarchy based on which the art is displayed, but rather visitors are hit by a wave of portraits as soon as they enter a room in the gallery. The visitor is met by a room of unfamiliar faces and throughout their journey they become increasingly curious about the stories of the individuals who now adorn the gallery walls. One such individual is the artist Lucian Freud, whose rather unconventional charisma was captured by the photographer Francis Goodman in 1945.

Goodman was invited to take photographs at Freud’s flat, 2 Maresfield Gardens, following their initial, and rather spontaneous, interaction at the Coffee An’ in Soho, London. Freud, a young artist who had recently graduated from Goldsmiths’ College, likely perceived such an interaction with a professional photographer as a sign that his art career had just begun. Goodman’s photographs, after the Second World War, which featured regularly in the British magazine The Tatler And Bystander, focused on covering high society, lifestyle, and politics.[1] Yet, the portrait of Lucian Freud was not as organised or calculated: the photographs were taken outside during winter, where the reflection of the cold winter snow on young Freud’s complexion acted as a natural form of studio lighting.

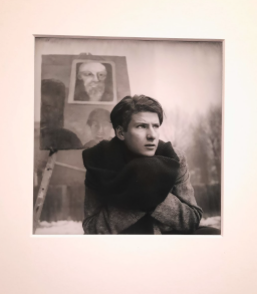

An unusual dynamic is consequently captured between the photographer and artist in the photograph of Lucian Freud. Rather than Goodman directing the sitting, it appears that Freud cultivated his own image as an artist through the medium of Goodman’s photography. As such, rather than the final photograph reflecting primarily on Goodman’s perceptions and insights as a photographer, the hardship experienced by Freud as a Jewish artist in post-war London is revealed. This is especially depicted by the piercing, though distant, gaze of Freud and his folded arms, attempting to protect his body from the cold winter in London. Freud emigrated to England in the 1930s, aged ten, alongside his family to escape Nazism. Whilst Freud was granted British Citizenship, the photograph illustrates the realities of migration as Freud appears unsettled by the harsh conditions of the outside from which the photograph was taken. Nevertheless, whilst a sense of starkness and coldness is portrayed through the slightly blurred surrounding landscape, this is in contrast to the extremely clear and determined glare of Freud himself. The photograph, therefore, was important to Freud as a reminder of the origins of his life as an artist and his ability to navigate the alienating environment of urban London.

The photograph not only depicts Freud as an artist, but one of his own paintings is also visible in the background. Goodman and Freud cleverly synthesise the mediums of paint and photography. The portrait depicts an old, slightly deformed man, who’s glance mirrors the direction of the artist himself. The man in the portrait and the artist are therefore connected, perhaps through similar shared experiences of isolation and hardship. Freud is sitting and his lower position on the ground means that the portrait is depicted above the artist. It is almost as if Freud was now directed by the art he created and the photograph reveals how interrelated his emotions or personality were to his artistic process.

Goodman’s other film negatives also reflect the unconventional beginnings of Freud as an artist. For example, one photograph depicts Freud with dishevelled hair placing the spout of a watering can into his ear. Again, he looks away from the camera and appears to be contemplating what he was discovering. Whether the watering can symbolises an old ear trumpet of the nineteenth century, or whether it was supposed to symbolise Freud as a plant being watered and nurtured, mirroring his growth as an artist, is unclear. Yet, what is apparent is that Freud was highly creative in his expressions as an artist, where he chose unconventional objects or settings to symbolise his rather unconventional journey as a painter.

Located on the second floor of the National Portrait Gallery, the photograph of Lucian Freud no longer depicts an unfamiliar face. The square film negatives considerably capture Freud’s life as an artist torn between an isolated past and his new outlooks for the future. The photographs, therefore, symbolise the beginnings of his careers, which was possible even if his experiences following the rise of Nazism and his migration to London were equally as difficult to interpret or comprehend than his interaction with a watering can.