Spilling out of the gates of the Sheldonian Theatre and onto Broad Street, the lengthy queue for a public reading of Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis (1915) took us by surprise: if we had been looking for a sign of the author’s enduring popularity, surely we had found it.

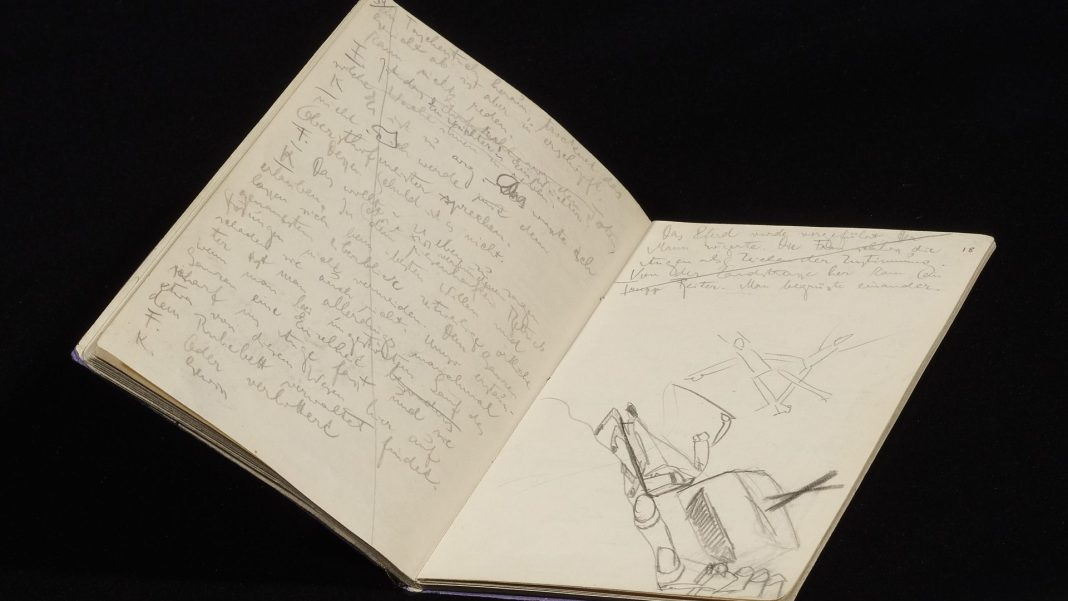

For the 100-year anniversary of Kafka’s death – to the day, the event marked a culmination of the ‘Oxford Reads Kafka’ program: a celebration of the author’s life and works that has involved exhibitions, talks, and performances throughout Oxford in the last few weeks. Although Kafka was Czech, and all of his work was written in German, the bulk of the Kafka archive has been held in the Bodleian Libraries for around 60 years.

The novella, recited in full for the event (using the recent Joyce Crick translation), follows Gregor Samsa – a man who awakes one morning to discover that he has turned into a “monstrous vermin”, usually interpreted as a cockroach-like insect. He attempts to grapple with his new physical state and ultimately becomes completely alienated from his family, who by the end of the story are only relieved at the news of his death.

Speakers ranged from diplomats to undergraduates, artists to University officials, including Vice-Chancellor Professor Irene Tracey. It was truly a convergence of all the walks of life that Kafka had inspired. The audience too – filling the Sheldonian almost to capacity – consisted of an impressive range of ages.

The event ran for almost three hours (an hour longer than scheduled), and whilst a few audience members inevitably had to leave early, the range of reading styles and alternations between different types of speakers provided just enough variety to keep the text alive and ‘transforming’ throughout the evening. In addition, each member of the audience was given a copy of the book to read along. There were certainly moments that dragged a little, especially in the second half (one of the couples seated next to us fell asleep) but these sections did not last long.

The welcoming introduction to the event announced new literary analyses of Kafka’s most celebrated work, discussing the potential readings of the book concerning ideas of body dysmorphia, self-doubt and disease (specifically Kafka’s battle with tuberculosis). This offered a new perspective to us, having both read the text before, which heightened the experience as a whole.

At one point, Oxford Biology professor, Tim Coulson, snuck behind the screen to change into a cockroach costume – a change which, due to the position of the projector, unintentionally cast a shadow onto the screen that gave the impression of the professor’s own metamorphosis, as spindly insect legs and polystyrene wings were flung about in haste. Whilst the shadow was likely accidental, it livened up the room before we encountered the harrowing third part of the book.

After flicking his new antennae over his shoulder with a stylish flourish, Coulson’s reading was interspersed with bouts of chuckles from the audience. There was something delightfully incongruous about Kafka’s words being uttered from a cockroach costume, by a Biology professor, in an almost 400 year-old University theatre: an absurdity that Kafka himself would perhaps have appreciated.

The intersection between Kafka’s works and broader social conflicts did not go unacknowledged. Kennedy Aliu, Vice President of Liberation and Equality at the Oxford Student Union, gave a brief statement before beginning his reading. Citing the ongoing conflicts in Sudan, Palestine, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, he asked that the audience use the text to “bear witness to suffering and atrocities”: situations that he described as “Kafkaesque”. His words were received with a brief round of applause. Similarly, both Jenni Lynam and Mia Clement (also involved in the Oxford SU) made references to the Palestinian flag in their outfit choices.

The standout performance of the evening was, undoubtedly, that of writer and broadcaster, Lemn Sissay OBE. He playfully brought out the emotional nuances of the text: gasping for air as Grete (Gregor’s sister) lurches to open the bedroom window, and leaping into a breathy falsetto for the voice of Gregor’s mother. Having written a stage adaptation of the novella in 2023, it is no wonder that Sissay’s connection to the writing shone through, and he could be seen subtly but enthusiastically gesturing along to the other speakers’ words throughout the evening.

The Bodleian Libraries website promised that the readings would “celebrate the power of Kafka’s voice today”, but it is difficult to know what Kafka, who died – virtually unknown – at 40, would have made of the event: a man who, by all accounts, had no designs on fame. In fact, the author requested that all of his unpublished work be burned after his death – thankfully ignored by his friend and literary executor, Max Brod. What was clear though, from the enthusiasm and range of the speakers and the attentiveness of the audience, was that the author’s words are just as vibrant and necessary as they were a century ago.

The event was an evening of poets, pupils and a professor in a cockroach costume: such a jumbled assortment would be difficult to pull off anywhere, let alone the Sheldonian Theatre, but it was one of which Kafka, we suspect, would have been proud.