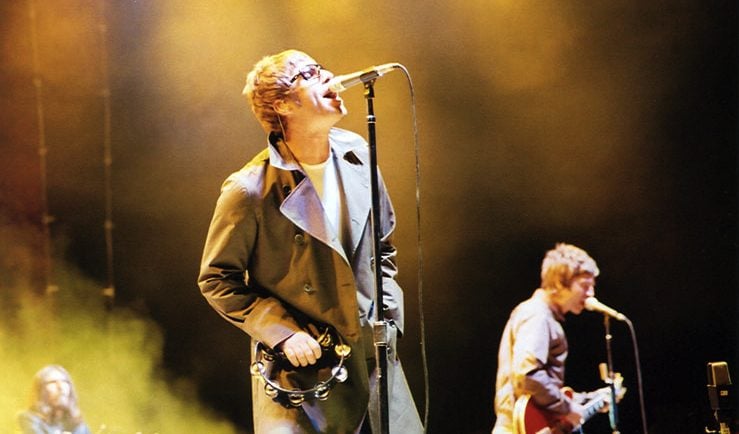

Competitive, difficult, and opaque. All words associated with the Oxbridge admissions process. More recently, however, they have been used by disappointed Oasis and Coldplay fans in relation to Ticketmaster. It’s devoted fans with less to spend (namely, students) who suffered most.

After the recent release of tickets for Oasis and Coldplay tours, the company has been accused of ‘advertising misleadingly’. Many have blamed the confusion on the website’s dynamic pricing model, where the price of a ticket varies to reflect changing market conditions, shooting up exponentially when met with great demand. This can be particularly detrimental to devoted fans, a large number of whom are students. The result is significant financial strain, resale market impact, and uncertainty surrounding the elusive nature of these tickets.

With this in mind, it is easy to feel hopeless at the prospect of joining the Ticketmaster queue system. However, there might be hope on the horizon for eager fans, as provisional legislation could aid demographics with less disposable income, such as students, to have their shot at bagging a ticket. The Competitive Markets Authority (CMA) has launched an investigation into Ticketmaster operations over Oasis concert sale. The organisation will evaluate whether the sale of those tickets have breached consumer protection law, which states that ticket sales sites must be transparent in their deals with consumers and must relay clear and accurate information about the price they pay for a ticket. As part of this, they check if Ticketmaster has engaged in ‘unfair commercial practices’, particularly looking into the transparency of their dynamic pricing model and the impact of time and pressure when paying for these tickets.

Whilst dynamic pricing is not automatically unlawful, its inherent changeability means that its operations are prone to fall into grey areas. In this case, the CMA is concerned with the potential lack of transparency when marketing these tickets, questioning if the information buyers were given about prices before checkout aligned with the prices they actually paid. A glance at X (formerly Twitter) reveals the frustration many fans felt during the process, with a sense of being ‘unfairly’ treated being a common theme. Some complain that one price was shown at the time of selecting a ticket but were confronted with doubled prices at checkout.

Another emphasis of the investigation seems to be the pressure put on fans to finalise their purchase within a short period of time. Heightened moments of pressure thwart customers’ ability to make coherent and rounded judgements, and when coupled with what are high prices for most of the population, people are thus more prone to make rash decisions that have heavy financial implications. Ticketmaster has used a timed element to control consumers’ perception of scarcity and demand, which potentially impacts their purchasing decisions in the company’s favour. It is a system that feels on the verge of exploitative.

However, the double standards surrounding dynamic pricing must also be considered. Plenty of other consumer services use dynamic pricing, such as hotels and airlines, and yet aren’t scrutinised in the same way. Dynamic pricing is a natural by-product of market-based capitalism, where demand and supply are bound to have an inverse relationship. It just so happens that we are experiencing potential misuses of it. Whilst Ticketmaster’s practices do seem like a breach of ‘clear and accurate’ information relayed to consumers, it is not yet evident whether Ticketmaster has actually broken consumer protection law.

Perhaps it would be helpful to think about why concert tickets are met with more disdain than their, equally dynamically priced, counterparts. In both the Oasis and Coldplay incidents, the central frustration seems to be centred around high, and hidden costs due to concentrated demand for a non-essential commodity (whereas a hotel or plane ticket is more likely to be a ‘necessary’ or sometimes ‘non-luxury’ purchase due to business). Fans are thus more likely to stress over the chances of securing a ticket for such an in-demand concert, but due to their desperation for an opportunity to see their band live, they are willing to pay a premium for tickets. Therefore, the problem isn’t inherently within dynamic pricing, but in Ticketmaster’s lack of transparency. One way to resolve this would be to declare the rate in which prices will rise based on consumer interest. By displaying that ‘this might be £70 now, but will go up in x number of hours after x number of tickets are left’, some fans are left still having to endure a premium, but they will at least know what they are getting into, enabling them to make an informed choice as to whether or not to remain in the queue. This is surely preferable to being ambushed by an extortionate price tag at checkout, after committing hours to the wait.

Some have also advocated for a set number of tickets that are left aside to be sold as ‘means-tested’ ones, where capital to support this could be raised through charities. Though bands have no duty to be a social service, it would help to broaden their prospective audiences – which can only be a draw. Student discounts are also a potential solution, with food chains, travelling services, and fashion brands offering yearly discounts. Some of these products on discount are non-necessities, too. The problem of bad actors and misuse arises, but this will always be unavoidable to a certain extent.

Whilst a lot of Oasis fans will be ‘looking back in anger’ due to their lack of tickets for the upcoming concert, the future is not all doom and gloom. Changes are afoot to increase access to these concerts, in whatever form they may take.