Oxford’s state-school admissions fall short despite outreach attempts

The University of Oxford undoubtedly has a reputation of elitism and yet more recently a focus has been placed on improving access and inclusion. This outreach feels more necessary than ever, especially when considering the University’s 67.6% proportion of students from state schools, which falls starkly short of the 93% of the UK population educated within this sector.

This investigation into representation of state-school students at Oxford University delves into the numbers and figures, exposing the reality of declining numbers and ineffective outreach schemes.

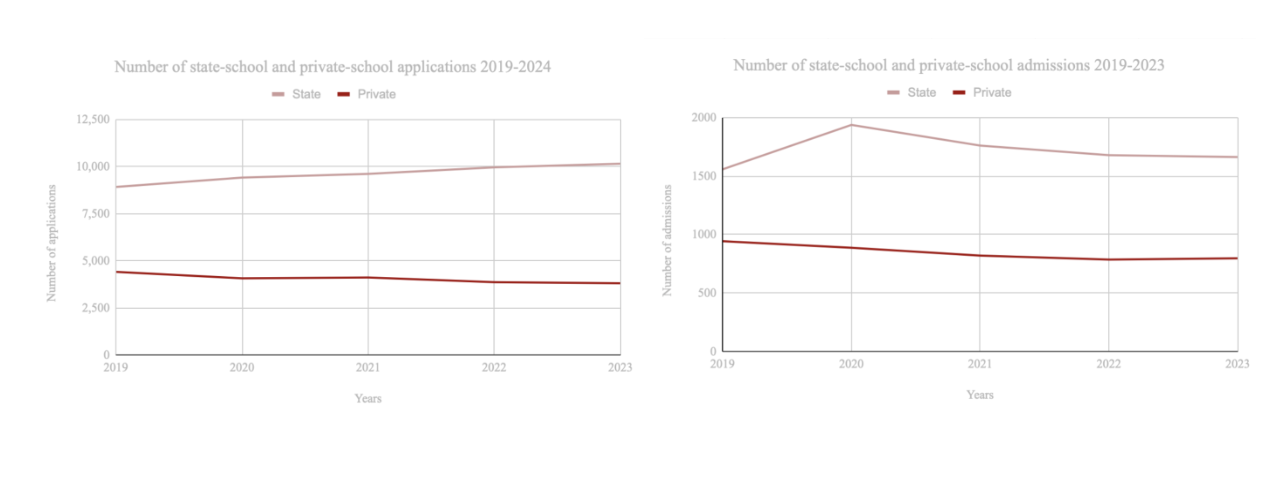

The University’s official admissions reports from the last five years paint a picture of progress and positivity, emphasising how the gap between private schools and state schools is narrowing. And to some extent it’s true. As graph one shows, in 2023 1,236 more state-school students applied than in 2019, increasing the proportion of state-school applicants by 5.3% over the last four years. On the other hand, private-school students have declined by a similar proportion with just over 600 less applications in 2023 than in 2019.

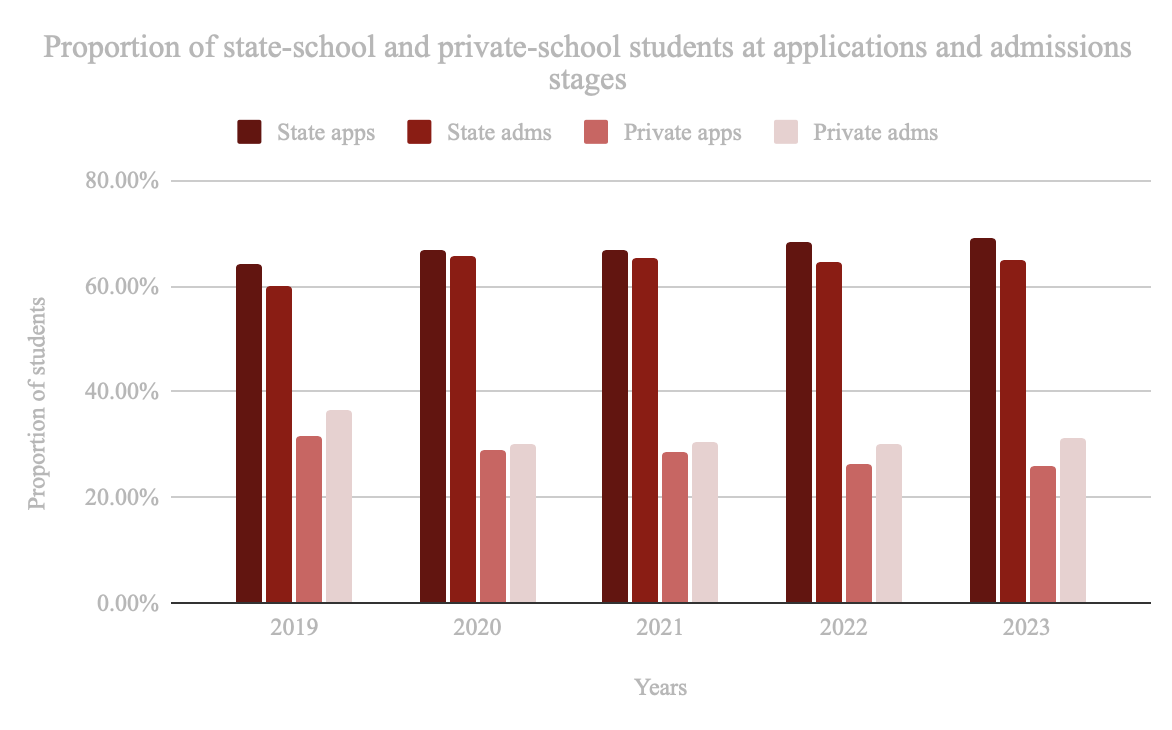

This trend can also be seen in admissions and from 2019 to 2023, the proportion of private-school students admitted fell by 5.3%, while the proportion of state-school students admitted into Oxford rose by 4.8% (graph two).

The University emphasises how their attempts to improve access have been successful throughout the report, drawing conclusions such as “the proportion of UK students admitted from the independent sector has decreased between 2019 and 2023.” Similarly, the report also says that state-school students represent “between 46.5% and 79.6% …for Oxford’s 25 largest courses,” a more generous statistic than the University’s overall intake of state-school students, which has not yet risen above 70%.

The issue of 2019-2020

Yet this progress is not as impressive as the statistics initially imply. The five-year time range used to track state school and private school access to Oxford University is a pretty standard one. And yet it is slightly problematic due to the outlier admissions year of 2019 to 2020.

The 2019 to 2020 application cycle marked a record year for state school admissions into Oxford with 21% of 9,411 applicants receiving offers (graph two). This contrasted the year before, wherein 500 less state school students applied, and 113 less offers were made to state school students. The unprecedented numbers of state-school admissions reached in 2020 have not been consistently matched in the following years. Indeed, since 2020 the gap between private school and state school access to Oxford has only grown bigger.

The data from the years post-2019 indicate stagnation far more than progress and the representation of state-school students at the University has been on the decline for the last four years. By 2022, the amount of offers given to state-school students had already fallen by 8.5% since 2020 and in 2023, 275 less state-school students were admitted to Oxford than in 2020.

The hidden facts

While the University’s admissions reports provide all the data on students from state schools and private schools, it is not made clear that the proportion of state-school students applying to Oxford University is consistently higher than the proportion of state-school students who are admitted, as shown in graph three. Furthermore, the proportional difference between the numbers of state-school students at both stages has risen by 4.2% since 2020, suggesting that this trend is only worsening.

Despite the numbers of students applying to Oxford from state schools only increasing, climbing to a record of 10,150 applications in 2023 (graph one), there has been no meaningful increase in the numbers admitted. While state-school students are increasingly encouraged to apply, the University’s admissions have in no real way yet matched this change.

In contrast, graph three also shows over the last five years there has always been a higher proportion of private-school students being admitted than the proportion of private-school students at the applications stage. The amount of this increase has also only grown since 2019.

It seems as if in recent years, Oxford’s progress in accessibility has stumbled into a period of increasing inertia. Improvements made in 2020 have been followed not by a meaningful change in the University’s demographics, but by a backslide into underrepresentation of state-educated students.

The schools

But it is not just the University’s own statistics that can provide insight into the representation of state-school students at Oxford University. The Spectator recently published a list of the top 80 schools that receive the most offers from Oxford University and Cambridge University. The data gathered from the 2023 UCAS application cycle shows how the proportion of high-performing schools is fairly evenly split between the private and state sector. Out of the 80 schools, 29 are independent schools and the remaining 51 are state-funded schools.

This would suggest that, if anything, state-school students have better chances of getting into Oxford University. However, within the 51 state schools on this list, there is still much stratification, with 29 being grammar schools and 17 sixth-form colleges. While all state schools are characterised by their lack of tuition fees, some are also fully or partially academically selective and others simply educate students post-16. Grammar schools and sixth form colleges tend to outperform comprehensive state-schools, achieving better A-level grades. Additionally, sixth-form colleges tend to be able to provide more extensive resources than comprehensive schools and grammar schools are noted to often disproportionately represent middle-class students. For example, in 2021 to 2022, 5.7% of pupils at grammar schools were eligible for free school meals compared to 22% in an average comprehensive school.

While comprehensive schools are still funded by the state, they are not selective and so accept all students regardless of academic performance and regardless of age. On this list of the top schools for Oxbridge admissions, only five, or 6.3% are comprehensive state schools.

The reasons

Another trend that Oxford University’s admissions reports reveal is that every year for the last five years, state-school students have been less likely to be admitted after receiving an offer than private-school students. In the 2023 admissions cycle, for example, 85.9% of offer-holders from state-school students were admitted contrasted by the 92.8% success rate of students from private schools. Furthermore, in 2020 the success rate of state-school students was 95.8% meaning it has fallen by nearly 10% in the last four years.

While it is impossible to say for all cases, one can assume that the vast majority of offer-holders who were not then admitted failed to achieve their required grades. Oxford University cannot, of course, be solely blamed for this. After all, it is true that private schools tend to perform better on examinations than state schools and in 2024 this performance gap reached its largest since 2018 with almost half of private-school students achieving As or above contrasted with only 22.3% of students at comprehensive schools.

However, the reasons why more private school students end up in top-performing universities, such as Oxford University, run a lot deeper than exam results. The resource disparities between the private and state sectors cannot be understated. In the last decade alone, the gap between private school fees and state school spending per pupil has more than doubled.

Private schools also tend to be able to better support their students with university applications. At Westminster School, who received the most Oxbridge admissions in 2023 jointly with Hills Road Sixth Form College, for example, students receive mentoring and preparation classes. A former student at the school told Cherwell how this was “absolutely invaluable for giving me confidence.” Similarly, St Paul’s School, which placed fourth on The Spectator’s list, employs eleven specialist UK university advisers to help students make decisions about their A level and university choices.

The Campaign for State Education told Cherwell some reasons private schools are better equipped to send pupils to Oxford University is because “they have many, many decades of experience in preparing students to apply to these universities… (and) many of them are likely to have personal connections to Oxbridge colleges.”

Therefore the gap between private schools and state schools is a highly complex issue and while one institution, such as Oxford University, cannot be expected to solely resolve it, they certainly should take all the steps they can to increase the University’s accessibility. And this has not yet been achieved. Oxford University still lags behind the national average number of state-school students by over 20% and in 2021 was the seventh lowest proportion out of the 24 Russell Group universities.

Outreach

But what is Oxford University doing to level the playing field? Outreach is a relatively new but important tool that Oxford among many other universities employs to encourage and support students from underrepresented backgrounds.

It was only in the 2010s that Oxford introduced structured outreach programmes. The UNIQ programme, a summer residential and one of the University’s flagship access programmes, was introduced at the beginning of the decade. It is now one of many initiatives run by the University. Oxford colleges also carry out their own outreach.

Cherwell received FOI responses from seven colleges – the Queen’s College, St Hilda’s College, St Edmund Hall, New College, Exeter College, Keble College, and St John’s College. This data shows that, as expected, state schools are the main target of their outreach programmes.

Outreach is definitely becoming more and more prominent and widespread and there is no argument that this is not a positive change. Yet in the last five years, there has only been a minor increase in applications from state-school students (graph one) and virtually no difference in the number of students from state schools who are admitted (graph two).

It might just be too early to tell. Most outreach programmes were first initiated between 2010 and 2020 and while perhaps this is not enough time to truly know, there is no evidence of positive change yet. It may not be fair to say that outreach has no effect but its success is yet to be mirrored in the University’s applications and admissions.

College disparities

Oxford University’s college system also adds greater complexity and the proportion of state-school students differs greatly from college to college. Mansfield College holds the highest number of state-school students with a proportion of 93.7%, which is in line with the number of students in state schools throughout the UK. However, this amount is 37 percentage points higher than the proportion of state-school students at Pembroke College.

The Campaign for State Education identified the college system specifically as a problem. They told Cherwell: “In the short term, the best thing to do would be to stop allowing colleges to control their own admissions. In both universities (Oxford and Cambridge) the proportion of state/privately educated students varies enormously from college to college and this clearly reflects the exercise of quite different admissions.”

Location, Location, Location

However, the picture painted by admissions statistics to Oxford University is not that simple. It is not just school type alone that affects access to Oxford but so does school location and in all areas, the same few locations are consistently overrepresented while the rest are nearly always at a disadvantage.

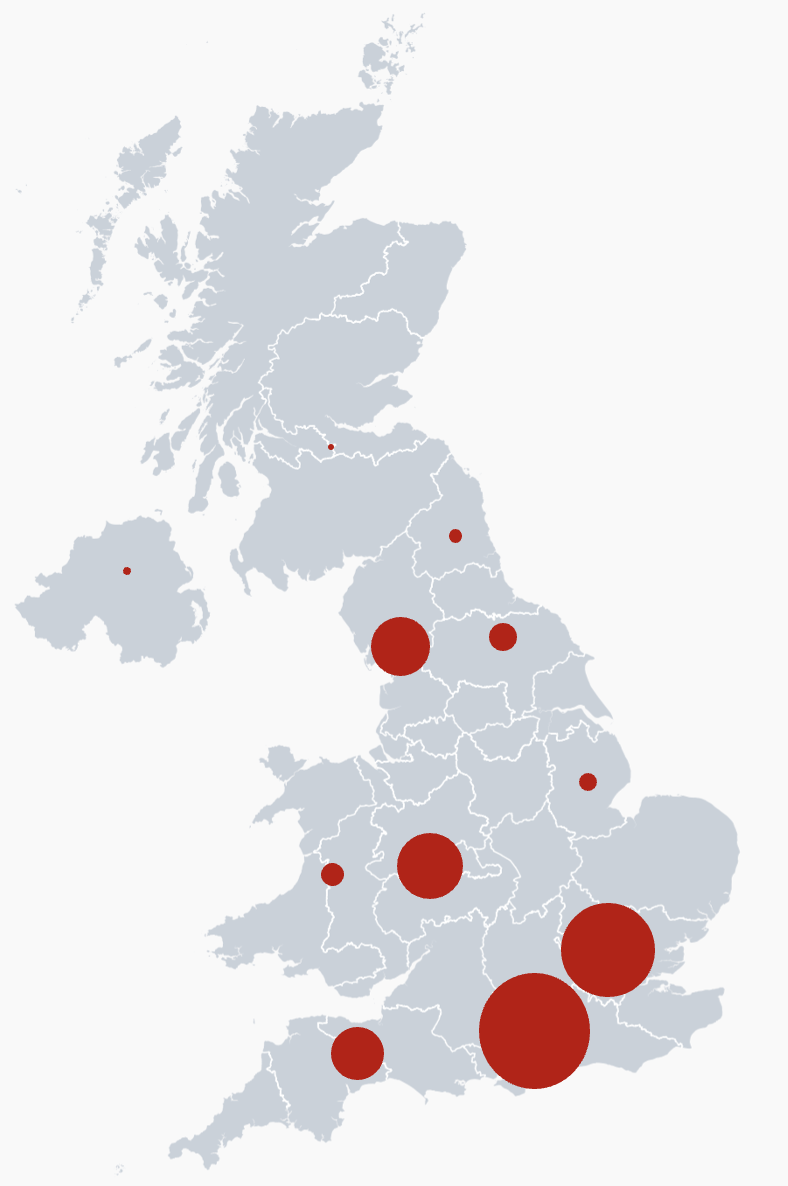

Oxford University’s admissions reports from the last three years show that London and the South East are favoured. Making up around 14% of the total UK population, the proportion of students from the South East who apply and are admitted to Oxford is nearly double that.

Contrastingly, the 11% of the UK population in the North West is not equally represented in the 8% of Oxford applicants and admittees. Students from Yorkshire and the Humber are also underrepresented and they make up only 5% of applications and admissions, despite this region accounting for 8% of the population.

Furthermore, when looking at The Spectator’s top schools for students who go onto Oxford and Cambridge University, this bias is also present. London and the South East are again the most popular with 38 out of the top 50 schools falling in these regions and all but two of the top 20. Only one school from the North East, Greenhead College, has made the top 50.

Therefore, this clear regional preference to London and the South East must surely have an impact on Oxford’s outreach attempts. The University’s regional outreach programme, Oxford for UK, describes how they aim “to help more local students from backgrounds which are currently underrepresented to make successful applications to Oxford.” This programme assigns different Oxford colleges a region for them to specifically target with their outreach programmes.

The statistics undeniably highlight the North East as an underrepresented area with the lowest number of applicants to the University coming from this region. Oxford for UK has assigned it links to three colleges: Christ Church College, St Anne’s College, and Trinity College. This is roughly the same number of colleges linked to Yorkshire and the Humber, the East Midlands, the West Midlands, the North West, Wales, the South West, and the East of England.

The bias towards London and the South East is also shown by the latter region being designated seven colleges to expand access in this already overrepresented area. Eleven colleges have links to specific boroughs within London, a subdivision made for no other area in the UK.

Madeleine Holt, founder of the Meet the Parents project, which encourages all families to support their local comprehensives, and a trustee of the think tank Private Education Policy Forum (PEPF), described the reasons for this regional bias as “affluence and selection”, explaining how these regions “have some highly selective sixth forms that have greater contact time than the average, and focus very heavily on getting top grades.”

The amount specific regions are interacted with by colleges does not correlate with their applications to Oxford University. The FOI responses from the seven colleges shows that the South West is targeted by outreach programmes two times as much as their students apply to Oxford (graph four).

Holt also stressed this problem, telling Cherwell: “I am concerned that colleges may be getting the numbers up by taking a disproportionate number of state school students from grammar schools or from highly selective sixth forms where they have built up a strong relationship over the years.”

Graph four represents the number of schools targeted by the seven colleges in each region and it shows that regional bias is stronger than a college’s designated outreach area. The schools involved in outreach are predominantly from London and the South East, while the North East as well as Scotland and Northern Ireland are far less affected. Indeed, regardless of designated links to the region, almost every college interacts with schools from London as a large proportion.

While this is not true for all colleges, outreach from St Edmund Hall, whose link region is the East Midlands, reached schools from that area over 80% of the time. However, this is not always the case and New College, whose link region is Wales, only interacted with Welsh schools less than 30% of the time.

What now?

It is clear that private-school bias is undeniably still a great issue at Oxford University. State school students continue to be underrepresented in one of the UK’s top academic institutions. The work of outreach programmes and initiatives are yet to have definite consequences on progress.

The Campaign for State Education told Cherwell: “the English private school system concentrates massive resources on the education of already privileged children and effectively undermines the education of 93.5% of our children…The best thing to do with it would be to abolish it.”

The University of Oxford said in response: “Oxford remains committed to ensuring that our undergraduate student body reflects the diversity of the UK and that we continue to attract students with the highest academic potential, from all backgrounds. The past few years have been challenging, with students, particularly those from socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, continuing to feel the impact of Covid-19 and the cost-of-living crisis. We continue to build on and expand our access and outreach activities and our new Access and Participation Plan will provide a renewed focus in attracting and supporting students who are currently under-represented at Oxford.”