CW: Animal Testing

An anesthetised rat was laying on its back, limbs splayed open. “Look away,” a group of first-year medicine students were told as their demonstrator stuck a metal rod into the rat’s head, cutting its brain stem so that it wouldn’t feel pain. Its tail jerked.

Practical experiments that end in animals’ deaths had been compulsory for Oxford University’s medical students. At the start of this academic year, however, Oxford’s application to continue teaching with animals was denied by the Home Office.

Universities in the UK are subject to the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, which regulates how they house animals, run experiments, and conduct harm-benefit analysis. Licenced accordingly, Oxford University’s animal experiments have decreased over the years but remains the second-highest amongst UK universities, just after Cambridge.

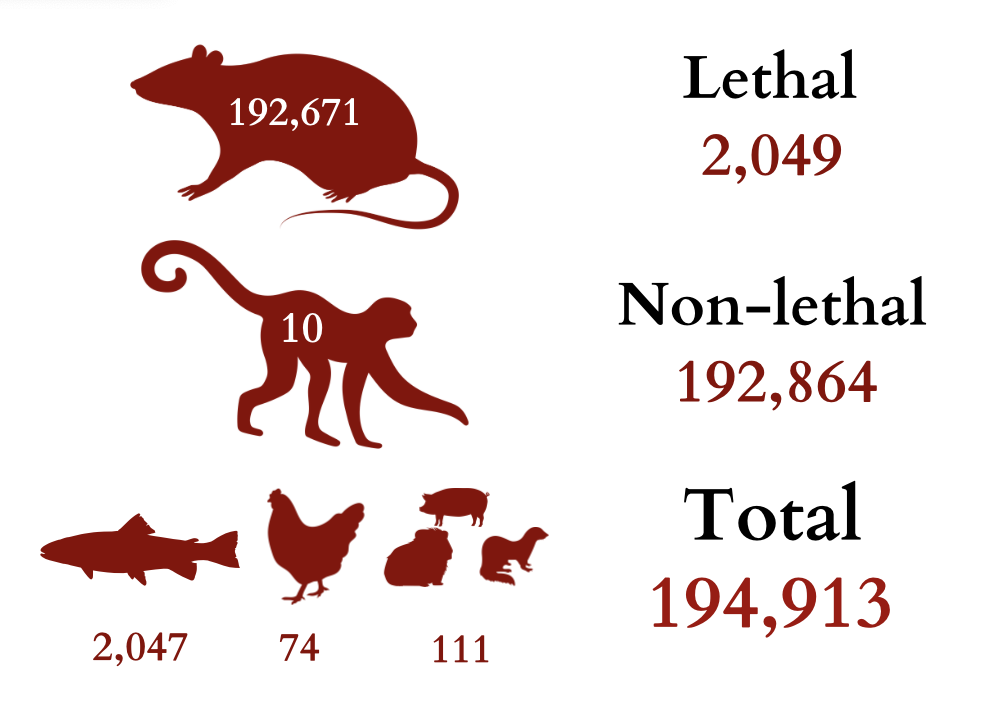

In 2023, Oxford performed procedures on 194,913 animals, including ten macaques – primates usually underwent skull implants and removal of brain tissue. The same year saw 2,049 deaths: Animals used for teaching constituted a small fraction of these ‘non-recovery’ procedures.

A contentious past

When Oxford’s Biomedical Sciences Building began construction in 2003, the work was soon suspended due to anti-vivisectionists’ intimidation – until the University was able to obtain an injunction and establish an exclusion zone.

In light of the building’s opening in 2008, an animal rights “fanatic” planned a series of terror attacks including homemade bombs: Two exploded in The Queen’s College sports pavilion and two failed to detonate on Green Templeton College’s property. They caused £14,000 of damage to Oxford, and the extremist was sentenced to a decade in prison.

Terrorist attacks – including parcels of HIV-infected needles – also targeted the late Sir Colin Blakemore and his family. Prior to becoming a professor at Oxford, he sewed shut newborn cats’ eyelids and later killed them to study their brains. His experiments significantly advanced the understanding of Lazy Eye – the most common form of childhood blindness – rendering it curable today. To Blakemore, animal research was a necessary evil he hated: He opposed animal testing for cosmetics and fox hunting, refrained from eating factory-farmed meat, and owned a pet cat.

Until this summer, a small group associated with this violent past had been protesting outside the University’s Medical Sciences Teaching Centre on South Parks Road – visible to medical students as they headed into their practicals.

Emotional toll

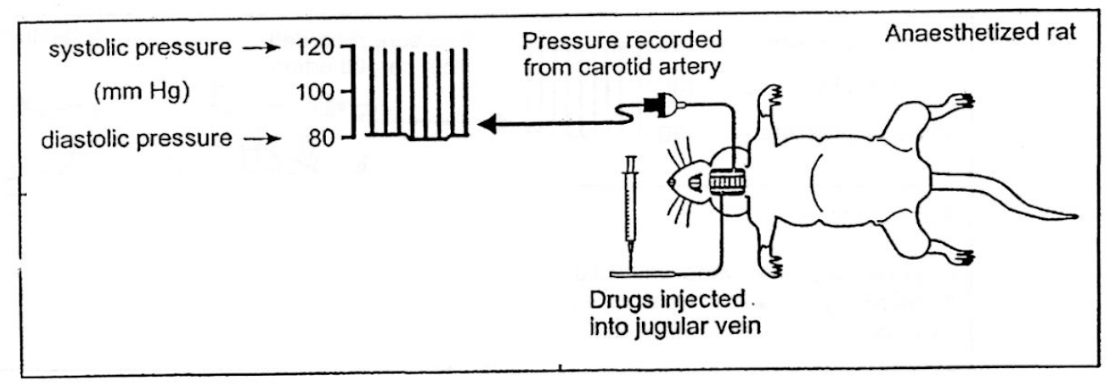

For the first-year Physiology and Pharmacology course, a compulsory practical class titled “excitation and blockade of α and β adrenoceptors” involved rats that are anesthetised, decerebrated, and injected with drugs, according to practical books viewed by Cherwell. In order to inject drugs into the rat, their jugular veins were cannulated with tubes, and in order to measure their heart rates as the response variable, electrodes were placed under their skins.

A second-year medicine student spoke to Cherwell about watching this experiment, which she did twice. Both times, the rat’s brain stem was destroyed to prevent reflexes and pain.

“The demonstrator told us to look away, but most of us kept looking anyway. He took this metal rod and stuck it into the rat’s head,” she described the decerebration. “Its tail shot up and moved in a very jerky sort of way, even though it’s completely under anesthetic and not going to feel anything.”

The rat was then injected with a sequence of six drugs – noradrenaline, adrenaline, isoprenaline, phentolamine, propranolol, and angiotensin II – to observe the effect of large dosages on its heart.

Although the experiment itself ended there, the rat was also dissected. The student said: “The demonstrator also cut the rat open, took its heart out, and showed us its heart beating in his hand.”

She said her friends could see her acting “visibly disturbed and distraught” after practicals such as this.

The teaching varied between different groups: Sometimes only the demonstrator injected the rat, while other times students were also able to do the injection and pass around the beating heart. One rat was used per every five to 15 students (with an average of 149 medicine students in each year, anywhere from ten to 30 rats were killed per year).

In another practical for Organisation of the Body course, pairs of students used forceps to “tear apart the beating heart” of chicken embryos in their eggs to observe under a microscope.

“I literally could not get myself to do it,” the student said. “For me this is a living thing, and you want me to kill it – I can’t.”

Additionally, several practicals use animal tissues such as chick muscles, guinea pig hearts, guinea pig intestines, and rat uteruses. The turnover of these materials vary. Some can be re-used between different students, but others degrade over the course of the experiment. While each animal only has one heart, many pieces of smooth muscle can be extracted from each life lost.

Vivisection or Video

Oxford was one of only two institutions in the country that still used live animals in education until this academic year. Over summer, the Home Office declined its application to continue, in line with the government’s shift toward limiting teaching licenses where suitable alternatives exist.

A University spokesperson told Cherwell: “The Home Office took the view that the use of live animals for teaching purposes was no longer justified and that teaching objectives could be achieved using alternatives such as videos and computer simulations.”

In response, the Medical Sciences Division replaced live animal practicals with video recordings of demonstrators doing the experiment. For one second-year student, this format is “perfectly fine” because she’s still learning the same material.

During in-person practicals she sat aside and took notes, “not engaging very much” because she felt uncomfortable. In contrast, she was able to focus better when she watched the videos.

While she acknowledges that students can gain insights from looking at animal anatomy, she believes it’s more helpful to look at human cadavers in the demonstrating room.

“Firstly, to pursue a career in medicine it’s a lot more helpful to understand the anatomy of a person,” she told Cherwell. “Secondly, we have consent to do this from the people who donated their bodies… Animals of course cannot do that. It just feels dirty.”

A fourth-year medic, reflecting on her experience, told Cherwell that although she believes the use of animals in education is justified in many cases, she “did not feel like the [rat] practical was of sufficient educational value”. She continued: “Especially as the animal died midway through the practical, it couldn’t even be used to deliver the teaching points it was intended to demonstrate.”

Another student against these practicals is Sheen Gahlaut, treasurer of Oxford Animal Ethics Society. Despite her personal belief that animal research is necessary for justified causes, she agrees with the Home Office’s recent assessment that these practicals are not justified.

The replacement with video recordings elicited mixed reviews. Gahlaut acknowledged that some medicine students argued animal research is a worthwhile endeavour, and some demonstrators shared their belief that it was unfair to deprive students of a learning opportunity.

Gahlaut also pointed out that Oxford’s “impersonal” way of rat vivisections wasn’t the only possibility. Rather, she described a research lab she volunteered at this summer where animal research was conducted with more sensitivity:

The scientists there put rats in CO2 chambers to study their intestines. In these moments, they would always ask everyone to be quiet and say: “We thank you for the sacrifice. We appreciate we’re doing something that is harmful for this creature, but we’re thankful that we can do this to advance research.”

On her experience with Oxford’s practicals, Gahlaut told Cherwell: “The worst part was the impersonal nature of it, how there was never really any thought or respect given [to the animal].”

A University spokesperson told Cherwell: “The pharmacology teaching practicals used humane approaches (terminal anaesthesia), minimised animal numbers, and were used to demonstrate fundamental pharmacological and physiological principles of clinical significance.”

Severities of suffering

The discontinuation of Oxford’s animal teaching licence does not affect its research licences.

While Oxford was conducting more animal experiments than any other UK universities until 2022, its numbers have now dropped beneath Cambridge’s. Over the years, the number of animals used at Oxford has gone down, from 226,739 in 2014 to 194,913 in 2023, classed into five categories according to severity of suffering.

According to Understanding Animal Research (UAR), an organisation that supports use of animals in biomedical research in a humane way, “sub-threshold” severity is defined as procedures which were originally expected to cause suffering but in retrospect did not. 64.1% of procedures in 2023 fell into this category. Meanwhile, 19.5% of the animals underwent “mild” procedures, 14.2% underwent “moderate” procedures.

“Severe” procedures were done to 2,139 of the animals in 2023. UAR defines this category as procedures where the animals are likely to experience severe pain, long-lasting moderate pain, or “severe impairment of the well-being”. It lists examples such as:

- Any test where death is the end-point or fatalities are expected

- Inescapable electric shocks

- Breeding animals with genetic disorders that are expected to experience severe and persistent impairment of general condition.

Lastly, 2,049 animals, including the rats used for medicine demonstrations, fall into the “non-recovery” category, meaning they never regained consciousness after being placed under general anesthesia.

From mice to macaques

The vast majority (98.5%) of animals that underwent procedures in 2023 were mice. Other species included rats, ferrets, guinea pigs, pigs, birds, and fish. Only 10 non-human primates – they receive greater protection under the legislation – underwent procedures in 2023, with one classed as “mild” and the other nine as “moderates”.

An official video titled “Animal research at Oxford University” shows shelf after shelf lined with plastic units, each with several mice inside. The footage details how the animals are housed in accordance with their natural environment. For example, mice have shredded papers to burrow into, while macaques live in social groups with stimuli, such as swings to play on and paper bags to forage from. The video doesn’t mention how the animals are used in research.

Experiments on primates are described on the University’s webpage. The macaques spend most of the time in group housing, with several hours a day dedicated to behavioural work, such as playing games on a computer screen for food rewards. They then undergo “surgery to remove a very small amount of brain tissue under anaesthetic”. After a few hours, they are up and about again.

Additionally, these macaques “often will undergo surgery to have an implant attached to the top of their heads. An implant may consist of a post to hold this animal still (e.g. during an MRI scan),” according to a virtual tour of the Biomedical Sciences Building’s primate research facility.

In a video, the animal welfare officer said: “It’s really important that we have ongoing assessments of their welfare, obviously for their own welfare…but also…that they remain that way for the science – we want to have normal animal models that will produce good quality data.”

Scientific consensus, ethical debate

There is a scientific consensus worldwide that some extent of animal research remains necessary. Nevertheless, animal research only forms a small part of the University biomedical research, with the vast majority using in-vitro techniques or humans.

The University’s website features several scientists discussing how their animal research advanced medicine. For example, Dr John Parrington used sea urchins, mice, and hamsters to find treatment for men’s infertility, while Professor David Gaffan uses primates to identify the processes behind memory disorders in the human brain.

“Just by being very complex living, moving organisms [animals] share a huge amount of similarities with humans,” the website reads. “There has to be an understanding that without animals we can only make very limited progress against diseases like cancer, heart attack, stroke, diabetes, and HIV.”

Other members of the University’s faculty disagree. Theology professor Revd Andrew Linzey, who founded the independent Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics, told Cherwell: “I fear the University has not yet caught up with the moral paradigm change that sentient beings, human or animal, should be treated with respect.”