Behind a constant veil of thick tobacco smoke, students relax and chat in a night of music and dancing far from Oxford’s usually formal settings. This might sound like a club smoking area, but it actually describes Oxford’s ‘smoking concerts’. An integral part of entertainment at the University in the early twentieth century, they speak to a time where smoking was an inevitable backdrop to everyday life. Smoking was more a constant part of its scenery than a University-wide ‘culture’.

This ghost of smoking past left me wondering: is there a smoking ‘culture’ at Oxford today? And how much has it changed?

Changing times

Those days of carefree smoking have vanished. The 1950s saw a definitive link established between smoking and lung cancer, and smoking rates have been largely on the decline ever since. When the Health Act of 2006 made some premises smoke-free, the University seized the opportunity to introduce a no-smoking policy inside its buildings. Philosophy students could no longer indulge in endless nights in their rooms spent staring at an unwritten essay question, a cigarette between their fingers.

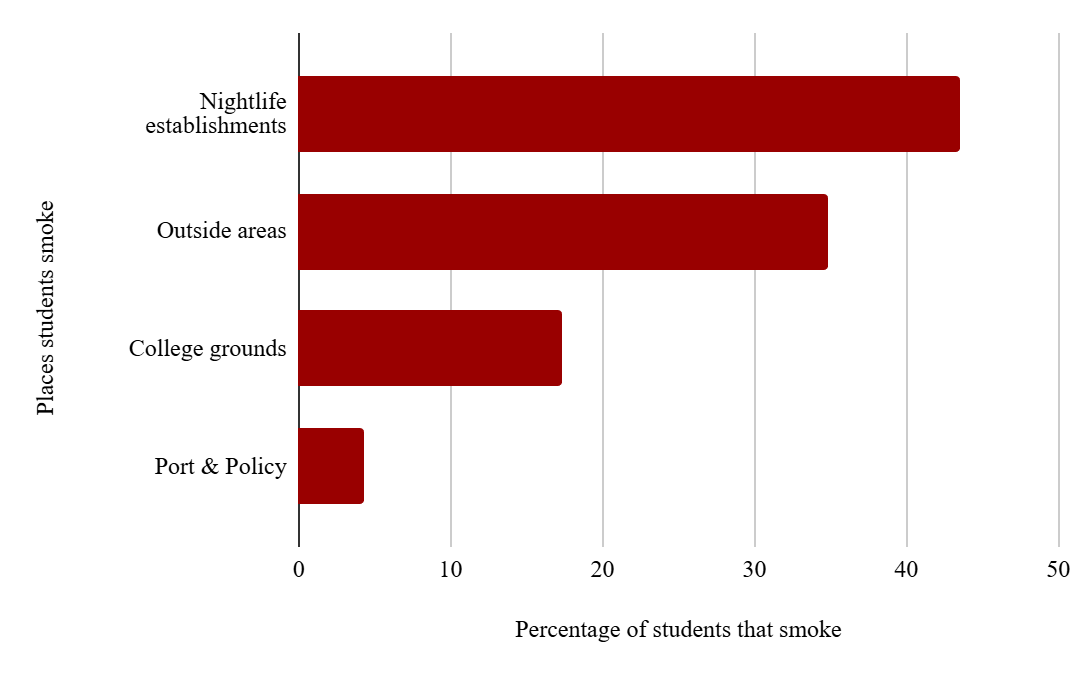

Cast out of doors, even smoking outside has faced heightened restrictions. Most colleges have restricted smoking to a few fringe areas. The areas in question are generally dingy, such as a small hole outside Lincoln College’s bar. When that’s the space on offer, little wonder barely any of Oxford’s smokers picked it up at the University.

Some colleges have banned it entirely from their main sites: Brasenose, Mansfield, and Queen’s to name just a few. Unhappily for smokers, but a victory for those concerned with the significant health threats of second-hand smoke. These policies have seen occasional reversals – St Peter’s College rowed back on a ban on smoking on-site in 2019 after a JCR majority opposed it – but the trend of increasing restrictions continues at pace.

Declining rates

Health concerns and the steady encroachment on smokers’ terrain has won results. Today, the dangers of smoking have never been better-documented: It is currently the leading cause of preventable illness, responsible for over 74,000 deaths a year. Whereas in the 1950s we might have expected 80% of students to smoke, a survey of 84 Oxford students showed only 23.8% now do so. The decline is unmistakable. Smoking has been limited and de-normalised as a habit for students. A smoker described to Cherwell his shock that: “At Oxford, if you smoke other students will ask you about it: ‘why do you smoke?’ I haven’t seen that anywhere else.” Ever fewer smoke, and ever fewer spaces allow them to.

Smoking survives outside bars, pubs, and clubs. Tobacco and alcohol go hand-in-hand as some of the substances available to students looking to cool off from the University’s “stress machine”, as described by one interviewee. Oxford’s nightlife helps students socialise and de-stress, and smoking provides both. Even within clubs cigarettes facilitate these roles – who hasn’t taken a breather from Bridge in its smoking area?

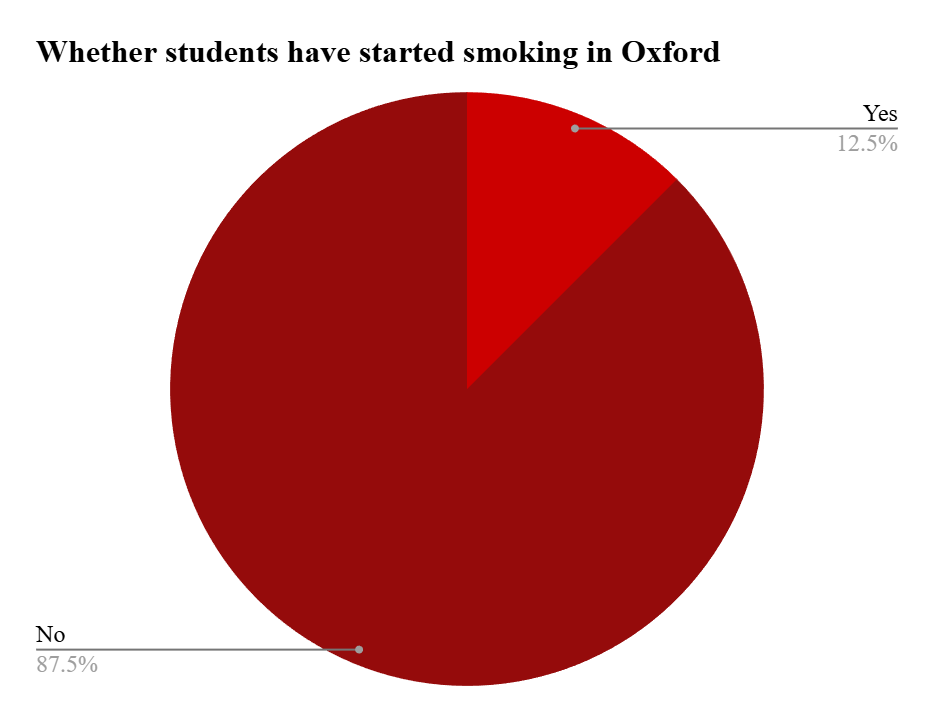

Even with this appeal, smoking wins few converts at Oxford. A few respondents discussed picking up smoking to deal with stress. One told Cherwell: “Oxford is stressful so there’s peace in smoking.” But 87.5% of respondents who smoked started before coming to the University. The alluring thought of a quick cigarette to calm the nerves before a collection only occurs to those already used to it.

Oxford’s smoking cultures

Carried over by incoming students as opposed to being home-grown at the University, smoking is more a passive practice at Oxford than a ‘culture’. It is in the background of other parts of life. This is exactly the same place it held when smoking was much more common, but now confined to some dank smoking areas and the cold streets of the city.

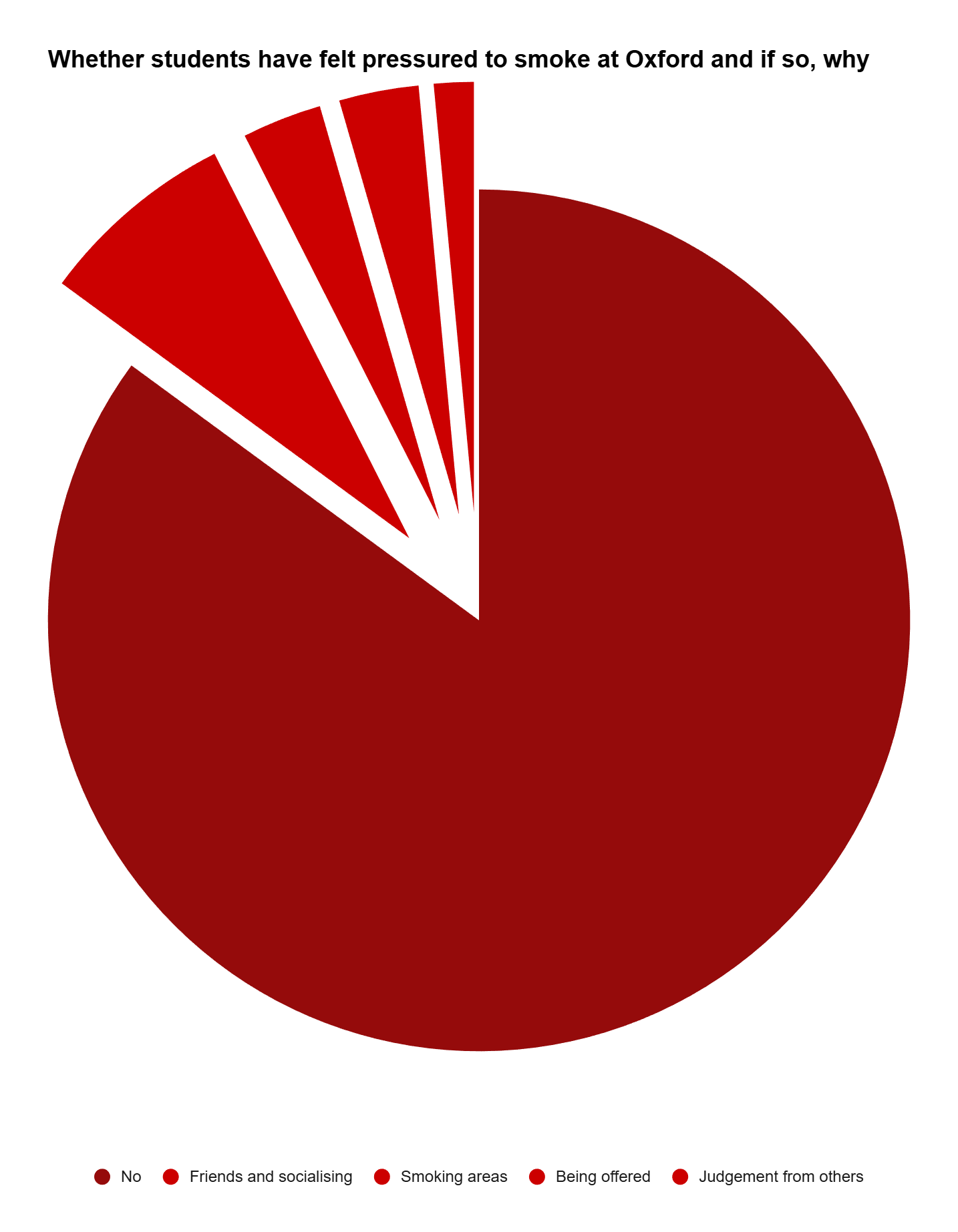

A narrow majority of the students surveyed disagree. 54% believe there is a smoking ‘culture’ at Oxford. Yet even here it was seen as largely passive. Non-smokers rarely felt pressured to smoke. If one person went for a smoke, others wouldn’t necessarily follow. But if non-smokers are naturally more likely to come from environments where smoking was rare, the culture shock of seeing students their age smoking semi-regularly might lead them to think there is a smoking culture. One non-smoker interviewed described exactly that, though they conceded this may be because they were “sheltered”. This chimes with how sceptical the smokers interviewed were of the idea of a university-wide Oxford smoking culture.

A wider consensus emerged among respondents that the case was more one of smoking cultures than a single one for the whole university. Here, different subcultures develop their own smoking ‘cultures’ as part of the images they wish to cultivate: the Oxford Union and Oxford University Conservative Association, “posh kids”, student journalism (The Isis even have branded lighters as stash). PPE and English had by far the highest proportion of smokers by subject – the same groups most likely to be active in these subcultures. The connotations of smoking here become more attractive: a social currency; a tool for hacking; something more glamorous or worldly. Smoking becomes adopted as a part of the subculture’s aesthetic.

The result is a feedback loop encouraging new participants to partake as well. Smoking becomes a social glue within these contexts, helping to cohere the groups by the opportunity it provides for socialising within them. Its position as a natural part of the subgroup’s culture and image is then consolidated. However, if you weren’t a part of these specific groups you wouldn’t necessarily draw the same associations. One interviewee told Cherwell: “I used to walk past the smokers outside Port and Policy without thinking about it. It was only when I picked up smoking and started attending that I saw it was a culture there.” This explains why drinks and stress were much more commonly associated with smoking as being more widely applicable.

Oxford’s cigar-smokers exemplify this. I was unaware such a subculture even existed, but a few respondents described it. Limited to a tiny group who can afford them and are “almost always dressed formally”, cigars are used by them as symbols of wealth and ‘refinement’. Freshers assimilate into the groups and adopt the practice, but otherwise the subculture is so compartmentalised as to be largely invisible. The symbols are only for each other to see – in these contexts smoking is as much a social signal as an outlet.

Generational Changes

Yet the future of smoking at Oxford appears to be a bleak one. With a declining proportion of smokers between years, it is increasingly endangered. Ever higher cigarette prices mean the habit can easily cost over £100 a month, discouraging any new intake. The decline may also be part of the wider trend in recent years of Gen Z proving increasingly abstinent. One in three is teetotal, as a shift occurs away from a ‘going-out’ culture and the substances like alcohol and tobacco that accompany this.

As ever fewer students participate in the ‘going-out’ culture and ever more pubs and clubs are forced to close, this has a knock-on effect on smoking. Those spaces are the very ones most closely associated with the practice. Its ground is yet more limited, leaving it with too little space to even become a University-wide culture. The subcultures are its last bastion.

At a more direct level, the proposed Tobacco and Vapes Bill of 2024-25 – set to be passed into law early this year – will ban the sale of tobacco products to people born on or after 1st January 2009. This raises the prospect of Oxford’s Freshers of 2027/28 being nearly entirely smoke-free. A black market will almost certainly develop, with products even more expensive and difficult to attain. Students still smoking will be far less willing to freely give them out, and Oxford’s casual smoking culture will face extinction. It will be too much effort for something banned in so many places to be worth it.

Smoking’s Future at Oxford

I can only speculate about what smoking cultures in Oxford will exist then, but I can think of two alternative paths. First, existing smoking cultures may slowly die out due to the expense and legal difficulties of the purchase. Second, smoking may become further limited to even fewer subcultures, but become more important in and culturally distinct to those contexts. If I had to place a bet, I would count on the second one, since it’s hard to believe smoking will lose all of its appeal by becoming illegal (you need only look at the UK’s drug culture to see supportive evidence – a subject for another article).

Smoking retains its allure: many identified it as a “cool” aesthetic for Oxford. The practice has recently seen a resurgence in pop culture, most notably as ‘a pack of cigarettes and a bic lighter’ became the symbol of Charli XCX’s provocative ‘Brat Summer’. In a context where it is limited and threatened, smoking gains its own attraction as something almost counter-cultural in breaking with those norms. It hardly possessed this trait when it was a constant presence around Oxford. It is precisely the restrictions designed to limit it that make smoking more attractive to specific groups.

The proven health dangers of smoking may mean that it is not a practice whose passing should be lamented. But it has evolved into a symbolic prop for many of Oxford’s vibrant subcultures, complementing their chosen aesthetics and images. Smoking has also maintained its older role as a passive practice occurring in the backdrop of Oxford’s nightlife and entertainment.

Nicotine is hardly the most attractive social glue. Still, the fact that it retains a social role despite its dangers and increasing restrictions is testament to its staying power. Any judgements on smoking’s demise may be premature. And while there has never been a University-wide smoking ‘culture’ as such at Oxford, different smoking cultures have developed and look set to continue, for now.