The #booktok stands that have become fixtures of bookshops across the country inspire intense feelings in me. It’s a mix of guilty curiosity, superiority, and bewilderment. BookTok, of course, encompasses a greater variety of interests than is represented in these displays, whose books are selected on the Holy Trinity of online appeal: ‘smut’, ‘spice’ and specific ‘tropes’. Yet in doing so, booksellers are (perhaps unwittingly) highlighting a side of BookTok and its audience which are the focus of a furious argument over the diminishing quality of literature being produced by the publishing industry. In the nuanced fashion which is typical of online discussion, critics decry book-tokkers as anti-intellectualist, while book-tokkers condemn its critics as conceited elitists. It certainly makes you wonder: is BookTok’s influence on how we engage and produce literature genuinely this impactful?

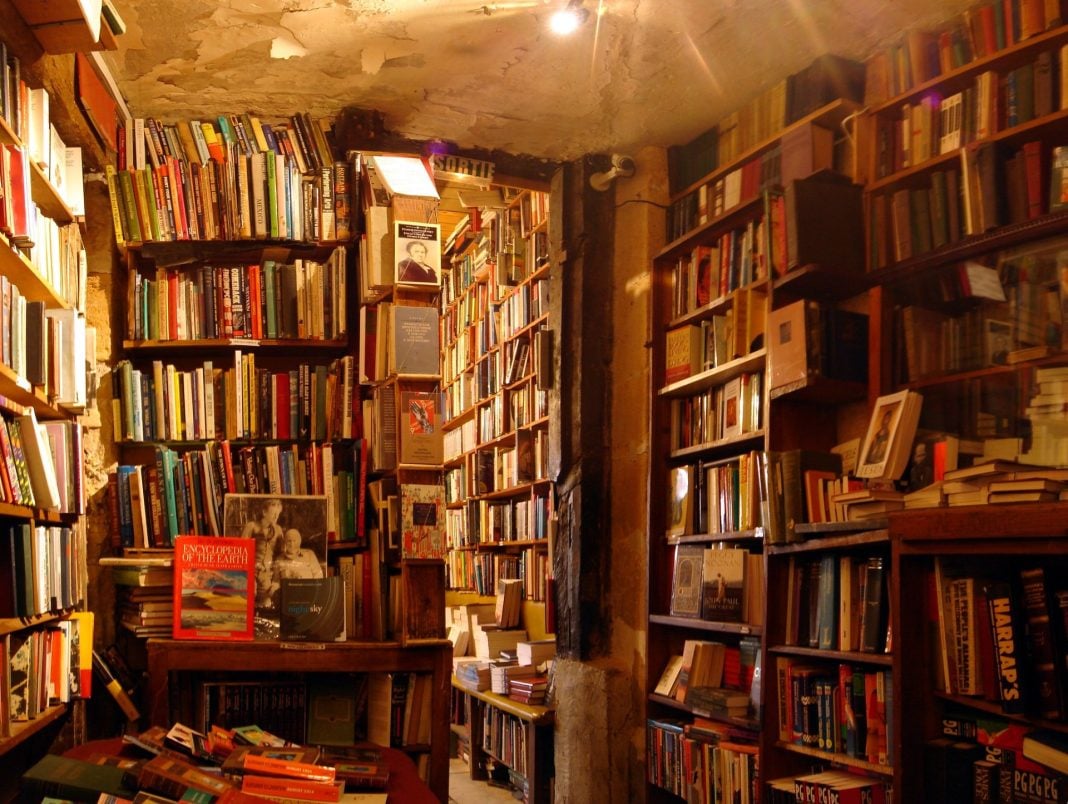

Influencers that have gained fame by analysing and recommending works online have become the faces of the publishing industry to an emerging generation of readers. Publishers actively encourage this by inviting figures like Jack Edwards, a prominent youtuber, to attend Booker Prize award ceremonies and literary festivals. However the charge levelled at these individuals is that by engaging in ‘trope-ification’, they lower standards of engagement to the point where derivative literature – works based on prior books and characters – can be published traditionally and dominate the book market. There are works like Red, White and Royal Blue, which demean the quality of publication through a reduction in standards – or so the online critics hold. To them, the similarity of the book covers decorating these #booktok stands is a visual symptom of the homogenisation of literature as Booktok distills novels down to mere checklists of tropes and stock characters. Even the way influencers market these books is predictable; an individual is framed by bright and bountifully brimming bookcases, identifying ‘Five books to solve X’, or ‘Five books for when you’re feeling X’.

Yet the argument that a form of culture can be debased by vacuous work designed to engage the plebeian taste is an old, tired argument, which has been rinsed and recycled since mass literacy became a phenomenon. This specific claim smacks of misogyny too, given that a majority of the authors who are perceived to benefit from this ‘trope-ification’ of reader engagement are Romance-writing female authors. Derivative literature has existed and enriched culture for decades – think of Bridget Jones’s Diary, which is a partial retelling of Pride and Prejudice. Any assessment of the overall quality of published books at any one time would be, by nature, arbitrary and subjective – there’s simply not enough evidence to suggest that ‘BookTok’ is even having a definitive impact on it.

However the popularity of tropes within the online book community has had an effect on the way in which readers engage with works. Because publishing is a market constantly responding to changes in profitability, this has, in turn, led to a reconsideration of how books are marketed. When books are promoted online, it is based on the number of tropes they fulfil, from ‘chosen one’ to ‘one-bed’. They are grouped together with works from completely different genres and contexts, instead united according to these categories. Literary tropes have always existed, but they’ve tended to be background influences, something rarely used to judge a book’s potential success. I’m disappointed to say that I’ve recently seen Jane Eyre marketed as ‘enemies-to-lovers’ – a particularly low point, in my estimation.

It is important to stress that the Romance sub-community is only one of BookTok’s many faces. There are sides which specialise in literary fiction, the Classics, and even nonfiction – most of which have their own distinct ‘trope’ checklists like ‘sad girl’ or ‘female rage’. Recognising the distinction of sub-communities is particularly interesting in itself. It speaks to the fact that like all online spaces, ‘BookTok’ is essentially operating as a market: there’s competition for visibility, followers, and potential brand deals. No matter how much genuine enthusiasm one might have for the written word, behind every video lies the pressure to make content that ‘sells’ and which will remain ‘visible’ – that is, receive high levels of engagement. What ensures engagement in the fast-paced, short-form world of TikTok is concision. This specialisation according to genre or type, funnelled by algorithms designed to repeat what has already been enjoyed, occurs because newness takes longer to engage people than familiarity. This means that analysis gets reduced and videos get shorter, which pushes the need for code words – like ‘enemies to lovers’ – which, economically, intimate the greatest amount of information about a book in the fewest seconds.

Videos specialising in the literary classics are often labelled inaccessible, while influencers promoting romance are labelled vacuous. The problem is never in the genre or type of works being read: it lies in the lack of variety and exposure to the unknown. But variety is hard to achieve in an online sphere, particularly because ‘BookTok’ is but a corner of an online world which subsumes all art forms under the guise of ‘content’ to be ‘consumed’. Film, music, art, literature – our exposure to culture has been reduced to a multivitamin, a once-a-day media tablet that we swallow quickly and with little attention to its specifics. The sensitivity needed to enjoy different art forms differs greatly between and within categories. They all require different palates and sensitivities, but the ever-productive churning force of the algorithm prevents this from developing. It also deprives us of the patience needed to, say, slowly savour a book, rather than skim to compete in the logging of as many books as possible on Goodreads.

This is not to say that online spaces like BookTok can’t provide community, inspiration and connection. However it is important to remember that BookTok is an artificial space, with underlying algorithms and structures that encourage artificial engagement. I’m not telling you to scorn the ‘BookTok’ stands in your local Waterstones, but simply suggesting that we also remember to appreciate the wider array of genres, editions, authors and contexts which await you on different shelves.