A two-bed, one-bath home in Cowley is currently listed for £450,000. In 1998, it sold for just £85,150.

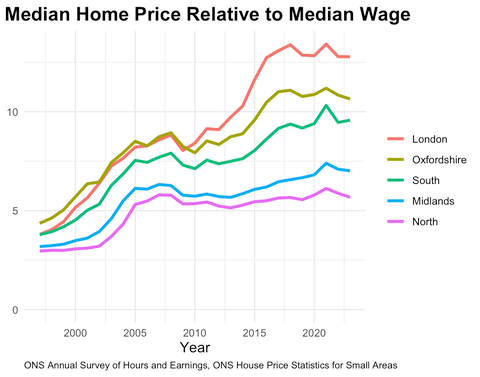

While wages have also grown over that time period, they haven’t grown nearly fast enough to keep up with rising housing costs. Across England, housing prices have more than doubled relative to wages since the 90s. In 1997, the median home cost about three or four years of median wages. Now, the median home in Oxfordshire sells for over ten years of wages, and in London it’s nearly 13.

The decline of homeownership

Across the country, rates of homeownership have declined, especially for young people. The homes people are left in are smaller: smaller than they were in the past, smaller than homes elsewhere in Europe, and a lot smaller than homes in other English-speaking countries. The average home in Britain is smaller than the average in New York, America’s most crowded city.

That house in Cowley, which costs over five times as much in nominal terms today as it did in 1998? In both years, it was an average-priced house in Oxford.

Why has home ownership become so much more unattainable in the UK? It’s no great mystery. Across the political spectrum, there is a broad consensus: for decades, Britain has not built enough housing.

In 2004, a government report found that England needed 270,000 new homes per year to keep up with demand. Every year – under Labour, the Coalition, and the Conservatives – the real number would fall short of that – sometimes far short. Every year, outside the pandemic and 2007-2009 financial crisis, housing prices rocketed ever upwards.

Finally, in 2022, the government didn’t fall short of its target! Unfortunately, that was only because Rishi Sunak scrapped the government’s target of 300,000 homes per year after years of Conservative conflictedness about it.

Labour’s 2024 manifesto promised 1.5 million new homes in England over the next parliament. The Conservatives one-upped them by promising 1.6 million (but only in the “right places”, like cities). Now, the Labour government has revamped the housing targets for local areas. It says the targets will be mandatory for councils, which are required to approve major development projects.

But it is still to be seen whether they have the political will to give teeth to this “mandate” – and how much of a dent it could put in a housing crisis that is 40 years in the making.

Oxford prices “excruciatingly high”

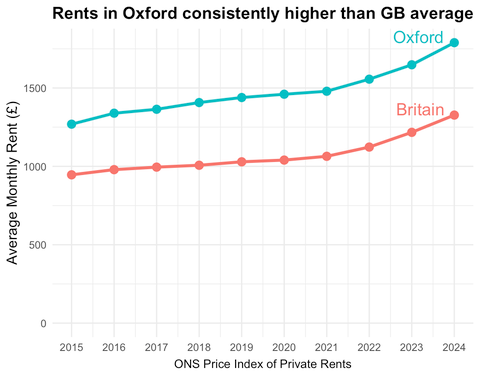

Over the last decade, rents in Oxford have been consistently higher than in the rest of the country, and is the most expensive city to rent in outside London.

Even for students seeking a shared house, it can be pricey. A survey conducted by Oxford Brookes’ Hybrid Magazine found that most students there were paying at least £800 per month for rent (£9600 per year).

Omer Mihović is an undergraduate studying Biochemistry. As a second-year at St. Edmund Hall, he does not receive college accommodation. Mihović is satisfied with the Cowley house he lives in with five housemates; his only complaint is the price.

Mihović told Cherwell: “As a foreign student, I generally find these rent prices excruciatingly high. But as far as I’m aware, the rents in Oxford are also considered a bit above average compared to pretty much everyone in the UK as well.”

Oxford City Council set an ambitious plan for local housing construction in its Oxford Local 2040 Plan. But the Planning Inspectorate rejected the plan for proposing too much housing – it relied on Oxfordshire’s rural councils to do much of the building in their own districts.

Oxford City Council notes what anyone who has walked across town might realise: except for the floodplains, the city itself is pretty filled up. Short of putting a subdivision on Christ Church Meadow or a skyscraper on a college quad, where is new housing supposed to go?

Choking off development

In many parts of the world, the answer would be obvious: sprawl outward. If there is demand to live in the city, it should just get larger. But Oxford’s growth has been intentionally choked by the green belt which surrounds the city – and takes up ten times more land than the built up parts of the city itself. Before the green belt came into effect in 1975, Oxford could grow as more people wanted to move in. But since 1975, the city limits have remained almost exactly the same.

The green belt is a popular idea, and it has succeeded at preserving the rural character of the surrounding countryside. But despite the ‘green’ in the name, much of the land is not particularly natural, and green belts can cause as much environmental harm as they prevent. With many Oxford workers priced out of the city, they have to move beyond the green belt and often commute by driving long distances across it. While many commute from Oxfordshire towns on the other side of the green belt like Didcot and Bicester, others commute from as far as Bournemouth. At times, Oxfordshire councils have offered to move residents to Birmingham and Cardiff due to lack of affordable housing here.

Even on vacant parcels of land inside the green belt, development is incredibly difficult. Local residents have been organising for four years against a plan to build 32 homes in Iffley, arguing that it would damage the rural character of the area and harm one family of badgers.

Even once the council approves a development, it’s not smooth sailing. A mixed-use development near Thornhill was approved by Oxford City Council in 2022, with every member voting in favour, but it still wasn’t signed off on until October 2024.

Local residents often object to new housing development in their area for a variety of reasons, sometimes getting labelled as ‘NIMBYs’ (for Not In My BackYard). New development can increase noise and traffic, potentially decrease the property values of existing property owners, and lead to change that residents just don’t want to see in their area.

But when every local council can veto new development which benefits the country as a whole despite imposing some local costs, housing doesn’t go anywhere. And the British planning system gives local residents some of the most power in the world to veto it.

The world’s strictest planning system?

In London, extraordinarily high prices are driven both by planning constraints and a lack of new land to develop in the city centre. There, so little land is open for redevelopment that Nazi bombing raids actually helped long-term economic growth – though this is partially due to historic preservation laws that prevent redevelopment. But in the rest of Southern England, where land is more plentiful, it is entirely planning constraints, and not a lack of land, driving up prices.

Peter Kemp, a professor at the Blavatnik School of Government, studies housing policy.

Kemp told Cherwell: “The house building targets now are being seriously thought about, and the government has talked about what it can do as part of its growth agenda. But the problem is planning in this country. In Britain, we have one of – if not the – most strict planning systems in the advanced economies.”

Unlike countries with by-right development and zoning – where housing development does not require approval in areas zoned as residential – councils in the UK individually scrutinise and can vote down every major development. This can lead to years of delays in planning. In both Oxford and England as a whole, about 30% of planning applications for housing were rejected from June 2023 to June 2024.

But Kemp also sees other challenges for the targets, including a strong “NIMBY lobby”, a shrinking and ageing construction workforce, and lack of funds for building social housing. Kemp says that while private developers are building about as much housing today as they were in the 70s, construction by local authorities has fallen dramatically.

Kemp continued: “If we really want to get anywhere near the level of housebuilding that the government wishes us to get to, we will need an expansion of building of social housing, particularly by local authorities.”

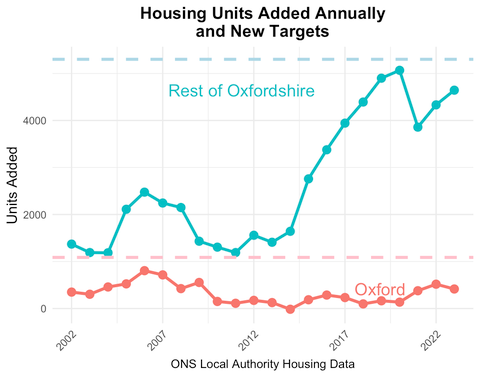

Even if England’s building targets are met for one year, or over the course of this parliament, it’s not clear that housing would become much more affordable anytime soon. In recent years, Oxfordshire has been fairly close to meeting the new targets set out by the government (Figure 3). Still, it is tens of thousands of units short of where it would be had it met its targets throughout the century.

Kemp told Cherwell: “If you’ve got a shortage that’s taken 40 years to build up, it’s going to take you many decades to solve that problem, and only if you’re determined and keep going through whoever is in power.”

Wider problems

The same local veto points and anti-development attitudes that have strangled housing construction have also hounded just about every construction project in the UK.

HS2, which is proposed to run 134 miles between London and Birmingham, has been under planning or construction since 2010. Over the same time period, China has built 24,000 miles of high-speed rail. You can travel between major cities in Italy, Spain, and France on high-speed rail. Meanwhile, HS2 is working through its 8,276 separate consents and spending £100 million on a structure that may or may not help to protect bats.

If you want to get to Cambridge, your best bet currently is to take an expensive train to London, or to hack the local bus routes by making a stop in Bedford. East West Rail plans to re-establish a direct connection between the university cities, but there is no set date for the line’s completion, and it is currently being held up because of worries about… bats and water voles.

Britain’s reservoirs are drying up as demand for water increases, but a new one hasn’t been built since 1991. Local opposition has rallied against a proposed reservoir in Abingdon even while demanding that something be done to protect the water supply (something else, that is). Winter fuel payments and the cost of electricity have been a major political hot potato. But under the Conservative governments, wind farms were effectively blocked if there was any local opposition at all, and solar farms were banned from most agricultural land.

Add this all up, and Britain’s sclerotic approach to building explains much of the cost-of-living crisis. Without being able to build a functional rail network, it can be cheaper for friends to meet in Spain than buy a train ticket from Newcastle to Birmingham. Without building housing, prices go up. Without building renewable energy sources, energy prices hit record highs.

Britain must pick a path on building

Dear reader, I have a confession to make. Despite having a strange interest in British planning policy, I am actually American. I’m just a wonkish Anglophile who happens to be a visiting student for one year in this fine country.

When I return to the University of North Carolina next year, it will be in an area that has made very different decisions about these matters than the UK has. The ‘Research Triangle’ area of North Carolina has nearly 2.5 million people today, up from just 700,000 in the mid-70s. Where there were tobacco fields just a few decades ago, one can now drive through 50 straight miles of low-density suburbs. This growth has been driven by tech jobs, the region’s universities, and the largest science park in the US.

Oxfordshire and Cambridgeshire could have followed this path – and in some ways it’s an enviable one. I will love paying much lower rent for a much larger house next year! But it would be a travesty to see all of England’s green and pleasant land paved over with American-style subdivisions.

Thankfully, that is not the only option. Oxford’s green belt is ten times larger than the developed parts of the city, and is itself surrounded by more protected land in the Cotswolds and Chilterns. With high-density development, even a small chunk of underutilised green belt land could go a long way towards alleviating the housing crisis and improving people’s quality of life.

God will not descend from the clouds to announce the objectively correct way to measure the value of badger families and rural preservation against housing sizes and economic growth. If the British people want to prioritise other values over affordable housing, faster trains, and a more prosperous society, they are free to do so. But Britain should be clear-eyed about those tradeoffs. In an era of stagnant real wages, rising homelessness, and eye-watering housing costs, it is right to wonder how much of the status quo is worth preserving.