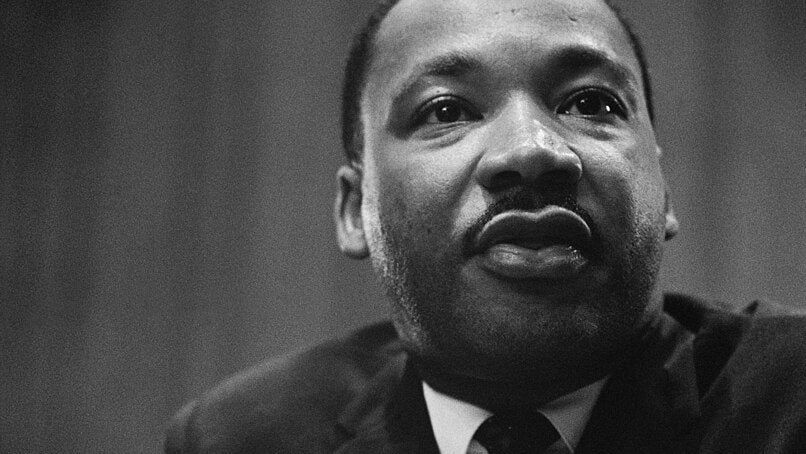

As Martin Luther King Jr Day rolls around on another 20th January, we are reminded of his enduring legacy: a dream of equality, justice, and a world free of prejudice. His vision transcends boundaries, resonating not only in America but across the globe. Yet, as many celebrate Dr King’s vision, one uncomfortable truth keeps gnawing at me: the assumption that racism is a uniquely right-wing, Christian, Western or white problem.

Having spent most of my formative years in Africa, I grew up surrounded by a shared identity. But when I moved to a multicultural UK, I encountered an assumption that lingers in many conversations: the idea that oppressed or marginalised groups can’t be racist. For many, especially outside Africa, it’s hard to fathom that racism could exist within communities that have faced discrimination themselves. But that’s a myth! One I’ve seen unravel in painful and personal ways. Anti-Blackness is very real and can be observed both subtly and overtly within Arab, Asian and even African communities.

This MLK Day, I want to challenge that assumption and shed light on why it matters. Dr King’s call for unity reminds us that confronting biases within our own spaces isn’t just necessary; it’s urgent. It’s uncomfortable but an essential first step toward change.

Anti-Blackness today

The struggle against anti-Blackness is both historical and contemporary. Lasting from the 16th to the 19th century, the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade are well-documented and critiqued. Less discussed, however, is the trans-Saharan slave trade – a system of human trafficking that spanned from the 8th to the 19th century. This trade involved the capture and transport of enslaved individuals from sub-Saharan Africa. It left a deeply troubling legacy, where Blackness became associated with subservience. Even today, remnants of this mindset persist, with terms like “abd” (slave) casually used in some Arab and North African communities, perpetuating systemic bias and cultural prejudice.

This legacy is starkly evident in the marginalisation of Afro-Iraqis and Black Moroccans, for example, who still face challenges from political representation, educational opportunities, to erasure in mainstream media. But perhaps the most grotesque contemporary manifestation of this legacy is through the re–emergence of slavery itself.

In 2017, reports from Libya – a country grappling with political instability after the fall of Muammar Gaddafi – revealed the existence of a modern slave trade targeting Black West African migrants. These vulnerable people traversed dangerous routes, only to be intercepted and held captive and sold like animals to the highest bidders across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Despite the gravity of these atrocities, the global and regional responses remain alarmingly indifferent.

My experience with anti-Blackness

Growing up in Nigeria, I didn’t think much about race – Black faces surrounded me. My experiences were far removed from the brutalities of slavery, but the cracks were still there. Colourism, for one, was everywhere. Lighter skin was celebrated, and fairness creams were treated like a golden ticket to beauty or success.

When I moved to the UK, I found the same issues reshaped in different forms, particularly within other POC communities directed against Black people. This became clear after transitioning from a 95% white primary school to a much more diverse secondary school in the West Midlands. Children of Caribbean descent would distance themselves from Africans, mocking my accent and calling us “fresh off the boat”. East Asian children, often discouraged by their parents from befriending Black children, avoided us entirely, citing fears of “bad influence”. South Asian and Arab classmates would crack “jokes” about Black people being lazy or aggressive. I saw a social hierarchy emerge, where every minority group seemed to position itself closer to whiteness as a marker of superiority.

And it didn’t stop there. This wasn’t just playground banter – it followed me into adulthood. Even at university and the Oxford Union, I’ve seen how deeply these biases run, often cloaked in intellectualised rhetoric or empty attempts at justification.

I’ve experienced these biases firsthand during my own presidential campaign at the Oxford Union. In student politics, the usual stereotypes – aggressive, lazy, or lacking competence and professionalism – were often also wielded as campaign tactics by other minority groups, even when blatantly disproven by facts. When coupled with misogyny, however, these prejudices form an especially toxic and damaging mix.

What’s most insidious is the contradiction in these attacks. Black people are demonised as aggressive or threatening yet simultaneously reduced to subservient or overly compliant caricatures. Never seen as fully human, trapped in a binary that constantly forces you to navigate perceptions. Over time, the pressure bottles up, and despite your best efforts, it explodes instinctively. Living with this tension for years takes its toll.

The most painful experience came from someone I thought was an ally, a friend who championed anti-racism. During a disagreement about handling an issue, where I suggested a more productive approach, their cutting response was: “[Of course you’d say that] like the good little Black boy that you are.” I was stunned. At first, I didn’t recognise the undercurrent of anti-Blackness, but in hindsight, their complicity in racist jokes and silence in similar moments became clear. I was an equal, but only so long as I knew my place; being useful in managing their campaign for office and thwarting political measures against them. That betrayal stung, but I’m thankful it shattered my own veil of ignorance, forcing me to confront how pervasive anti–Blackness remains, even within circles of supposed solidarity.

Anti-Blackness isn’t exclusive to far-right thugs or historical slavers – it thrives in the most subtle places and mindsets. People who have experienced discrimination and should know better, those who’ve read the books, delivered the speeches and championed equality, still perpetuate tired stereotypes, exposing the glaring contradictions in their rhetoric.

The persistence of anti–Blackness

Across much of Arab television, Black individuals are often reduced to harmful stereotypes. Slurs such as the N-word are often thrown in, trivialising the humanity of Black individuals. Black characters are routinely typecast as housemaids, labourers, or criminals, rarely depicted as professionals, heroes, or leaders. An absence of positive representation reinforces stereotypes of the inferiority of Black people, creating fertile ground for more troubling forms of anti-Blackness to thrive.

One such is the exploitation of Black migrant workers in Gulf states where institutionalised racism is deeply entrenched. The kafala system ties workers’ residency to their employers, effectively stripping them of autonomy. Many sub–Saharan African domestic workers endure gruelling hours, physical abuse and withheld wages. Employers often confiscate their passports, leaving them trapped in exploitative conditions. One particularly harrowing case in Kuwait saw an Ethiopian domestic worker clinging to a seventh-floor balcony in a desperate attempt to escape abuse. Her employer, instead of helping, chose to film the incident – a stark example of the power imbalance and dehumanisation at play.

Language often plays a significant role in normalising anti–Blackness. Terms like “abeed” (slaves) and “Azzi” (a slur akin to “Negro”) are casually used in conversations, stripping Black individuals of dignity and perpetuating long–standing stereotypes. Beauty standards exacerbate these issues, with lighter skin often idealised and darker-skinned individuals, particularly women, excluded from mainstream representation. The aggressive marketing of skin-whitening products across the region and the whole of Africa reinforces the belief that Blackness is undesirable. Even cultural traditions play a role in normalising discrimination: in Lebanon, a popular sweet called “Ras al-Abed” (head of the slave) was renamed “Tarboush” due to its racist connotations but similar products elsewhere still retain the original name.

Why talking about this matters

In many places, discussing anti-Blackness remains taboo. Nationalist narratives often erase racial diversity, promoting homogenised identities that leave no room for acknowledging racism. In Morocco, for instance, authorities have historically denied the existence of racism altogether, dismissing it as a Western concept that doesn’t apply to their society.

Talking about this issue with some of my Arab friends highlighted just how deeply rooted, yet seemingly innocent, the inability to address anti-Blackness can be. Within families and social circles, raising the topic is often met with resistance. Terms like Azzi are brushed off as harmless jokes, while those who push back are dismissed as overly sensitive or divisive, creating a stigma around addressing the problem – much like what happens in Western nations like the UK.

Dr Martin Luther King once said: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” This truth resonates profoundly because it reminds us that combating anti–Blackness cannot be selective. It is not just a Western or white issue – it is a global one. If we are serious about justice, we must confront anti–Blackness wherever it exists, even when it is within our own communities. The first step is breaking the silence, no matter how uncomfortable it may be.

The FBI labelled Dr. King “the most dangerous Negro,” fearing the power of his uncompromising call for justice paired with his extraordinary capacity for forgiveness. His words endured because they didn’t shy away from hard truths – they demanded better. If we truly believe in equality, it’s time to hold up that same mirror to ourselves and confront what we see. Change begins when we stop making excuses.