In its early days, the University of Oxford was largely constituted by private religious halls, which post-reformation provided a space for Catholic and non-conformist Christian denominations to study at the University. In 1918, Oxford gave some of these halls permanent status, affording them lasting membership of the University, without needing to receive a royal charter to achieve full collegiate status. These halls remained partially responsible for their own governance, and held onto their religious identity beyond that of the University.

Today, there are four Permanent Private Halls (PPH) in Oxford University. The largest of the four, Regent’s Park College has aspirations of joining the ranks of Oxford colleges, and is often confused for already being among them. Next door, Blackfriars Hall, which shares a site with the a priory under the same name, is home to the white-robed friars spotted throughout Oxford. Wycliffe hall, on Banbury Road, is largely a hub for ministerial training, with 40% of students studying for ordination. Finally, Campion Hall, tucked away behind Pembroke College, is distinctive for its humble size, housing only 20 students. These PPHs are collectively home to just over 500 students.

PPHs are an area of mystery to most Oxford students and often subject of various myths. With some students previously having rumoured that “PPHs are cults”, and “Regent’s is being bought by St. John’s”, Cherwell spoke to the heads of all four PPHs to shed some much needed light on the smaller cousins of Oxford colleges. In looking at the governance, finance, and culture of PPHs, Cherwell found that while they formally and academically align with the University, some students are left feeling more pressured than welcomed by their hall.

Ownership & Governance

All four PPHs are either governed independently, or in part by a religious institution. Between PPHs, the specific role given to the governing institution varies. For the two largest PPHs, Regent’s Park, affiliated with the Baptist Union, and Wycliffe Hall, linked to the Anglican Church, their association starts and ends with their accreditation to train ordinands, ministers of the Church. The two halls are registered as their own charities, in effect existing and operating similar to other colleges. Emphasising their independent nature, Regent’s Park Principal, Sir Malcolm Evans, told Cherwell: “There is no sense in which the College can be said to be subject to any form of ‘religious governance’ or external influence beyond the University”.

By contrast, Blackfriars, affiliated with the Dominican Order, and Campion, affiliated with the Jesuit Order, exist under respective parent-charities which hold trusteeship. Accordingly, these PPHs give a greater degree of governance to the religious orders with which they identify. Blackfriars’ Senior Leadership Team is partially composed of members of the Dominican Order, and Campion’s Governing Body includes a permanent representative of the Jesuits in Britain.

The governance of PPHs is twofold, however, since they are all subject to Oxford’s “Regulations governing the Permanent Private Halls” additionally to their independent governing body, which includes stipulations such as as each fellow must be approved by the relevant faculty or department, as well as being subject to the University’s general policies on good practice, like all other colleges. As Blackfriars Regent, Fr John O’Connor explained, Blackfriars Hall “first and foremost” complies “with the letter and the spirit” of University policy.

Finances & Security

As subsidiaries of larger charities, Blackfriars and Campion lack their own endowments but receive funds directly. The Master of Campion, Rev Dr Nicholas Austin, told Cherwell that this arrangement affords them greater financial security than they would as an independent hall, like Regent’s Park or Wycliffe, since their patron charities have additional funds which may be allocated to the hall in times of need. The Regent of Blackfriars accorded with this view, explaining that whilst the Hall primarily generates its own income, the Dominican Order offers additional financial support by, for example, investing in premises that the hall can use at subsidised prices.

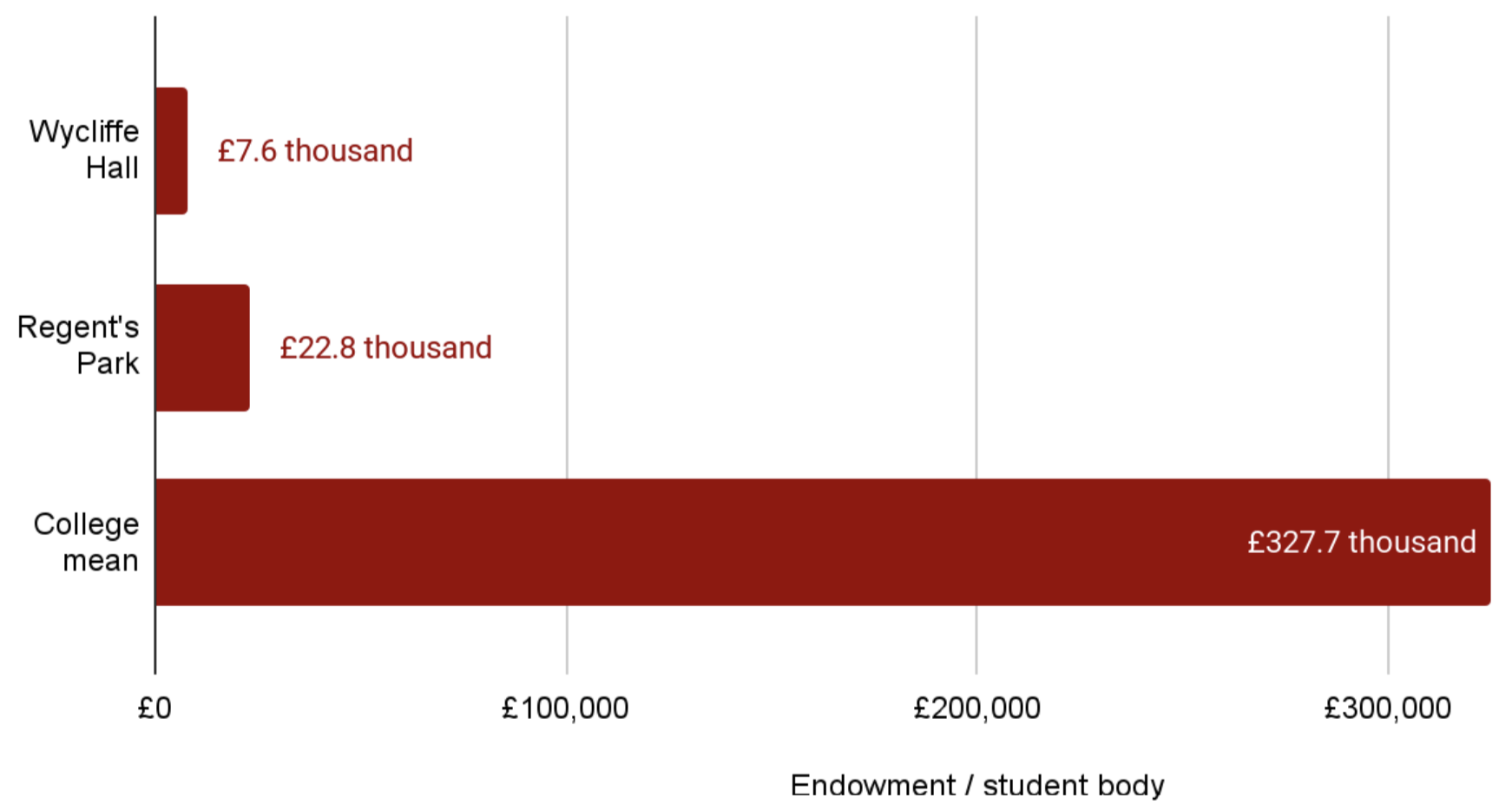

The financial situations of the independent Regent’s Park and Wycliffe are less favourable. Since they lack full college status, PPHs did not receive the same attention in 2024’s Disparity Report. For the year 2023/2024, Regent’s Park reported an endowment of £4.8 million, a mere 2.9% of the average endowment amount at each Oxford college for 2023/2024 (£160.2 million). Similarly, Wycliffe’s endowment of £561,000 weighed in at only 0.3% of the college mean. Taking into account the comparatively small student bodies of PPHs, Regent’s Park’s endowment-student ratio of £22.7 thousand and Wycliffe’s £7.6 thousand were eclipsed by the college mean of £324.7 thousand.

The comparatively precarious situation of these PPHs is due, in part, to their exclusion from the College Contribution Scheme, a University-wide fund collected from colleges proportionally to their wealth, from which poorer colleges can apply for grants. When the Scheme was redrafted in 2019, Regent’s Park JCR advocated unsuccessfully for PPHs to be included, despite motions of solidarity being passed by colleges such as New College and Merton College. In his proposal, the then Regent’s Park JCR president, Noah Robinson, wrote “[the Scheme] seeks to help poorer colleges, but ignores the poorest of all”.

Whilst the Principal of Regent’s Park told Cherwell “the College copes perfectly well without these benefits”, a 2024 report on the experiences of students at PPHs noted that budget constraints impact the living standards of PPHs, visible in “the absence of gyms, bars, and sports facilities on-site… a lack of variety in dining options” and “fewer and less elaborate” social events. Further, the “book grants, travel grants, accommodation bursaries or other financial support” available to students at colleges remain inaccessible to those at PPHs.

Overall, students believed that these financial disparities impacted their social and, to some extent, academic experience. Whilst the report recognised that poorer colleges face similar challenges, it held that “these problems can feel more pronounced within PPHs due to their particularly small student populations and unique religious ethos”.

Culture & Environment

Whilst Regent’s Park rivals other colleges in size, with a student body just slightly larger than Harris Manchester College, the other three halls are distinctive for housing a comparatively few students – most markedly Campion, with a student body of only 20. These smaller PPHs agreed that their modest size was a strength, attracting students seeking a more community-oriented Oxford experience. “It thus allows us to offer highly personal services”, Blackfriars’ Regent told Cherwell; “students are known by name, not only by other students, but also by the staff”.

These three PPHs also saw the religious principles of their halls as an attractive feature for applicants, including those who identify with a different religious tradition, or none at all. For example, Rev Dr Nicholas Austin, Master of Campion Hall, explained that the Jesuit Order’s central value of cura personalis, or pastoral care, long precedes the University’s recent increased recognition of the need for student welfare support.

All four heads were keen to point out the religious diversity of their hall, as well as the lack of faith requirement for applicants. The heads of Campion and Regent’s Park told Cherwell that students who identify with their respective religious orders represent a minority in their halls, and the other two affirmed that their communities are by no means defined by a singular religious background. Nevertheless, they did not see this diversity as cause for secularisation, as other Oxford colleges have tended to. Instead, Campion, Wycliffe, and Blackfriars have an opt-out system in place whereby all candidates who applied to other colleges, but were pooled to them, are offered the opportunity to decline the PPH and be considered by a different college.

Rather than changing their culture to accommodate a wide variety of students, these halls instead ensure that all students are there of their own volition, though the SU raises concerns that the opt-out system does not do enough to ensure that applicants feel that they have full agency over their choice to study at a PPH. Blackfriars told Cherwell that in returning to the offer pool for consideration by another college, these students are not disadvantaged whatsoever in their overall application to the University. However, the SU report found that some applicants doubted this assurance, as one student accepted a place at Campion, having been pooled there from Blackfriars, and felt pressured to accept the place, recommending a consistent, University-wide opt-out system.

Regent’s Park differs from the others in this respect, since it lacks that opt-out system for pooled candidates. The Oxford Student Union recommended that these students should be given the choice to be reallocated in their report, recognising that “the smaller size and strong religious ethos [of PPHs] may not align with [pooled applicants’] expectations or personal interests”. As well as providing non-Baptist students with the option of a secular Oxford experience, an opt-out system would ensure “that these communities are filled with individuals who are excited to contribute to and benefit from the experience.”

Despite the recommendations of the SU, Regent’s Park decided against implementing an opt-out system, and students continue to be pooled to the PPH, without the choice to be reconsidered. Regent’s Park Principal disagreed with the SU’s view that students at the hall are denied a secular experience, since “coming to Regent’s does not make a student subject to any form of governance or influence other than that of the College and University”, defending the position that students may be readily pooled to Regent’s, just as they would to other colleges.

One undergraduate at Regent’s Park who spoke to Cherwell defended the decision, since the choice to opt out may result in diminished student numbers and diversity.

Tolerance & Inclusivity

The SU report continues: “Rather than an opt-out provision, undergraduate students conveyed that they would like Regent’s Park to adopt a more inclusive atmosphere to other religions and beliefs, rather than an atmosphere of simply tolerance.” Whilst there is no pressure to engage in religious life at PPHs, many non-Christian students felt marginalised, feeling merely “‘allowed’ rather than genuinely welcomed”. As well as a lack of Halal and Kosher provisions, students reported that non-Christian religious events across PPHs receive comparatively meagre funding and support.

Recently, Regent’s Park saw an incident of antisemitic graffiti. In his statement condemning the act, the principal wrote: “Mutual respect and toleration and the freedom of religion or belief is a central pillar of Baptist identity and thus foundational to the ethos of Regent’s”. One transgender Jewish student at Regent’s Park told Cherwell that the statement’s emphasis on the Baptist identity only left him, and other Jewish students, feeling more isolated, since “they once again centred Christianity even when the matter at hand was about an antisemitic hate crime”.

In response, the principal told Cherwell: “Whilst fully respecting this point of view, this was not the general reaction to the statement: indeed, many students and staff expressed quite the opposite view, commending the College for the support which it offered and the open and transparent stance that it had taken.”

The same student told Cherwell that their experience made them feel that the PPH prioritises a certain “religious identity & experience above others”. The student eventually negotiated a switch to Linacre College to complete their postgraduate degree, following the PPH’s handling of incidents which left them feeling “marginalised and excluded on the basis of [their] identities”.

Regent’s Park Principal told Cherwell: “we reject the suggestion that we only ‘tolerate’ those of ‘other religions or beliefs’. The very suggestion implies that there is a bias towards those of a particular faith or belief tradition, which is simply not the case. It is just plain wrong to suggest that those of some faith traditions, or of no religious faith, are prioritised over those of others, as generations of students who have studied at Regent’s can attest. We seek to provide for the needs of all our students.” Additionally, he drew attention to Regent’s Park being unique among Oxford colleges and PPHs for issuing a specific Trans Inclusion Statement. Blackfriars’ Regent also stated that the hall welcomes students and fellows of diverse sexual and gender identities.

Not all student experiences are uniform, however, as one Muslim undergraduate at Regent’s Park told Cherwell that the PPH’s religious associations have fallen in the background of their experience. Despite being the only undergraduate wearing a hijab in their matriculation photo, she said “I don’t feel bothered or ushered into the corner”, adding that the PPH accommodated her request for a room close to a bathroom for religious reasons, as well as a dedicated prayer room. Other than saying grace before formals and hearing the echoes of the chapel choir across the quads – trademark signs of any Oxford college – she found that Regent’s Park’s religious associations are, simply put, “not in your face”.

(Im)permanent Private Halls

For some PPHs, these financial and cultural tensions have reached breaking point. Greyfriars Hall, governed by the Capuchin Franciscan Order, closed in 2008, citing an “unsustainable level of investment required…, both in personnel and finance”. In 2022, St. Benet’s Hall, governed by the Benedictine Order, found itself in the same position, as the University decided against renewing its PPH status due to financial inviability, and its buildings were sold to St. Hilda’s College.

The following year, St. Stephen’s house gave up its PPH status, in order to be able to award the Church of England’s Common Award, transitioning to an Anglican theological college which only takes on ordinands and those already ordained.

By contrast, St. Peter’s College, Harris Manchester College, and Mansfield College were once all PPHs before they received collegiate status. Regent’s Park’s Principal expressed the hall’s ambitions to make the same transition. For him, the question was not ‘if’, but “how and when this is to be brought about”.

The heads of Wycliffe, Blackfriars, and Campion were comparatively content with the middle ground that PPH status affords. For Campion and Blackfriars, the arrangement allows them to benefit from the academic offerings of Oxford, whilst still existing as subsidiaries of their parent-charities. Any perceived tension, they insist, is mistaken since the orders’ values complement those of the University. For the independent Wycliffe Hall, Principal Rev Dr Mighael Lloyd explained the value of PPHs in terms of a symbiotic relationship, whereby “ordinands help keep Wycliffe the Christian community that the vast majority of our non-ordinands are looking for”, whilst non-ordinands ”help our ordinands to stay ‘normal’”.

PPHs stand with each foot in a different world: one in the modern, secular University, and one in the religion-centred communities. Whilst some, like Regent’s Park or St. Stephen’s, opt to commit to one over the other, for those stuck in the middle, the compromises leave a distinctive mark on their students’ experience.