Over a career spanning more than five decades, Gered Mankowitz’s lens has chronicled the evolution of music and culture, immortalising icons like The Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, and Kate Bush. Now based in Cornwall, he devotes himself to exhibitions, publishing, and selling his evocative prints.

Growing up as the son of renowned writer Wolf Mankowitz, young Gered was no stranger to cameras. Professional photographers regularly visited the family home for magazine and newspaper shoots. Even then, Mankowitz showed early signs of his future calling: “I was always the one who wanted to look into the back of a camera, always the one coming up with suggestions.”

But it was Peter Sellers, the legendary actor and a family friend, who crystallised Gered’s destiny. Sellers brought to Sunday lunch what would prove to be the instruments of inspiration: a Hasselblad 500C kit and one of the earliest domestic Polaroid cameras. Mankowitz recalls: “I’m weeping with laughter as Peter gets my brother and I to position ourselves for a shot in the style of Tom Thumb, and once it’s taken, he begins counting down the Polaroid’s development time in this insane Swedish chef voice.” When Sellers departed, Gered turned to his father and declared, “I want to be a photographer – and I want a Hasselblad.”

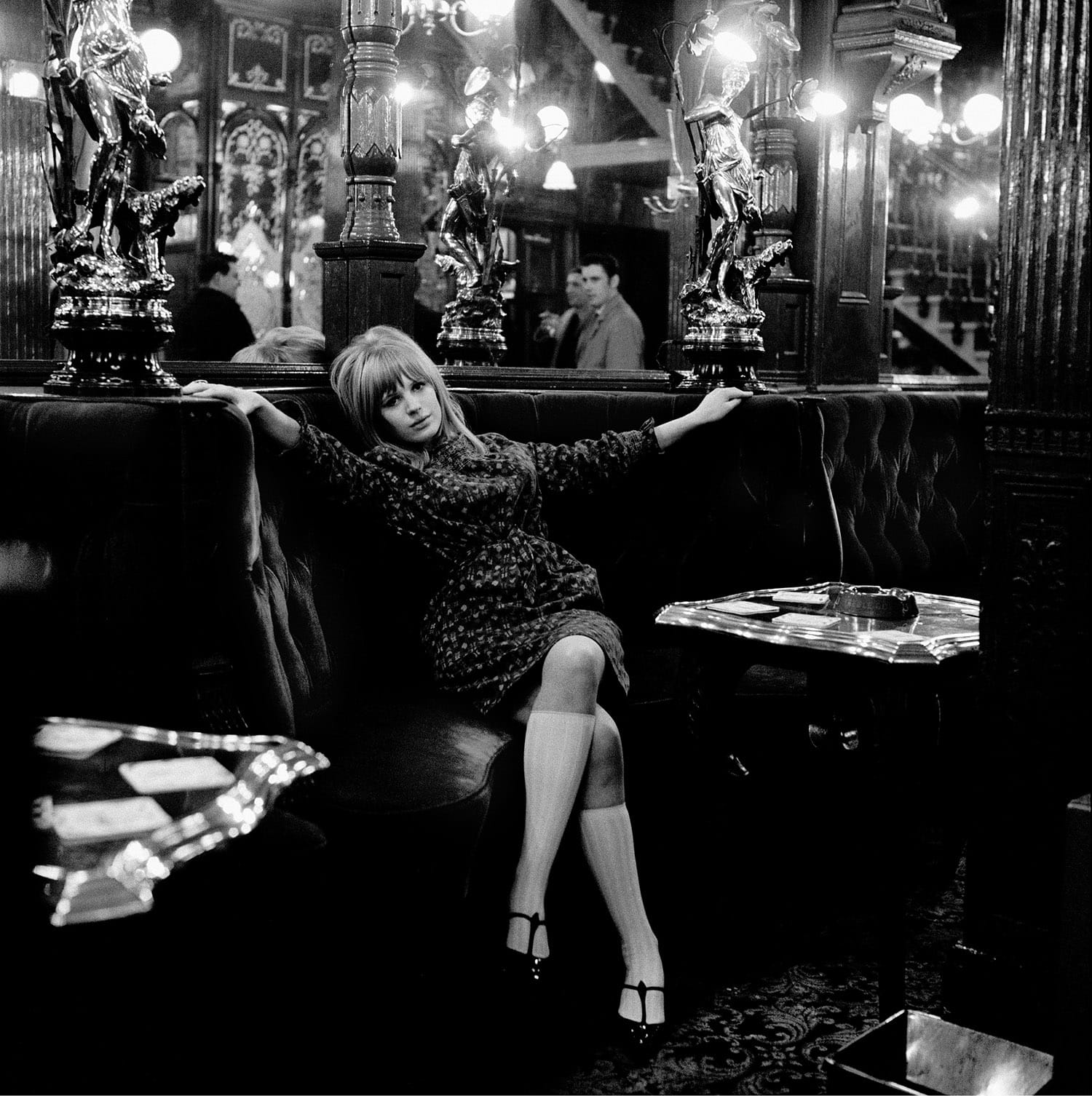

The riotous cultural upheaval of the 1960s offered the perfect canvas for a young photographer. Rock and roll, breaking free from corporate constraints, was finding its raw, authentic voice. Mankowitz found himself at the vanguard of this visual revolution, forging bonds with artists eager to shatter the more clean-cut images of the past.

“What I found working with these young artists was they wanted to break away from the ‘corporate look’. And I wanted to break away from that as well,” Mankowitz reflects. This rebellious spirit led to extensive experimentation, much of which proved too radical for contemporary tastes. Yet Mankowitz’s naïveté proved to be an unexpected asset. “I didn’t know you weren’t supposed to shoot into the sun. I just thought it looked amazing when everything flared. And so I just shot,” he laughs. This fearless exploration aligned perfectly with the burgeoning youth movement of the time, though he modestly adds, “Not that I think any of us thought we were part of a movement”.

One of the most iconic moments of Mankowitz’s career came with the creation of the Between the Buttons album cover in 1966. Mankowitz had spent 18 months working closely with The Rolling Stones, describing himself as “very much part of the team”. After a nocturnal recording session at Olympic Studios, he turned to look at the band on the pavement and inspiration struck.

“They were stoned, hung over and bedraggled, but they looked absolutely fantastic,” Mankowitz recalls. Armed with a homemade filter crafted from black card and Vaseline-smeared glass, he captured the band against the early morning light of Primrose Hill. “The filter worked absolutely beautifully, dissolving the trees and the sky into a sort of ethereal, slightly trippy tone. It was almost like a painting.” The shoot lasted a brisk 40 minutes before, as he puts it with a laugh, the cold and exhausted band “basically told me to fuck off.”

While the Stones and Jimi Hendrix often dominate discussions of Mankowitz’s career, his portfolio spans decades of music history. From multiple sessions with Suzi Quatro and Slade (“one of my favourite bands”), to the haunting elegance of Kate Bush and the avant-garde energy of Eurythmics, Mankowitz approached every subject with equal devotion. “I put as much into photographing Sweet as I did [in]to photographing the Stones.”

This egalitarian approach extended to his penchant for working with artists early in their journeys. “I’ve always had exciting artists, creative, beautiful, interesting people to work with,” he says. “I like working with people whose image isn’t quite formed yet. I like being part of the process of creating an image for somebody.”

The intimacy of portraiture lies at the heart of Mankowitz’s photographic philosophy. “I love simplicity,” he states. “A lot of my pictures are incredibly simple because I don’t want to take away from the subject. I always said to people, ‘You’re the hero in this photograph. Nothing to do with me… people must see you, always.'” This ethos proved particularly transformative with subjects like Annie Lennox, whom he describes as “like a chameleon… so beautiful and dynamic.”

Mankowitz’s choice of black and white versus colour photography reflects both practical and artistic considerations. While the ’60s often dictated monochrome due to printing limitations, Mankowitz’s artistic instincts played an equally significant role. For Jimi Hendrix, he found that black and white imbued the images with “dignity and respect and a sort of gravitas”, though he admits that it was “a stupid mistake commercially”. Other artists simply demand colour. “Kate Bush, for instance… her image demanded colour, because of her hair, her skin, her lips. Colour was how she should be seen.”

Perhaps most revealing is Mankowitz’s perspective on what makes for meaningful photographic encounters. Despite the prestige it might bring, he admits his “stomach would sink” at the prospect of photographing modern megastars like Taylor Swift – not due to any artistic reservation, but because of the barriers to genuine connection.

“Photography is a very intimate thing for me,” Mankowitz explains. “A portrait of somebody is a very intimate thing. It’s really them and me and the camera.”

This desire for authenticity has always guided his work, preferring to photograph artists early in their careers when genuine interaction was still possible. This philosophy explains why Mankowitz never actively pursued subjects, instead letting them find their way to him. “I like working with people whose image isn’t quite formed yet,” he reflects. “I like being part of the process of creating an image for somebody. I don’t mean imposing an image. I mean looking at them and feeling what it is that they’re trying to do with their music, with their work and finding a way of getting that across in a photograph.”

Despite Mankowitz’s embrace of digital photography’s conveniences, he maintains an analogue sensibility. “I impose an analogue pace, an analogue environment, even when I’m shooting digital,” he explains. Limiting himself to twelve frames and resisting tethered shooting, he prioritises an unfiltered connection with his subject. “You just try and get some sort of understanding between you and the subject. Some continuity, some fluid intimacy.”

However, Mankowitz’s views on AI are less accommodating. “AI is a nightmare for photography,” he asserts. “AI-created images have a superficiality, an illustrative quality to them. They just don’t look real.” He’s particularly disturbed by the animation of his historic photographs: “I’ve seen people animate my photography, taking pictures I did in the sixties of people and having them animate and singing along with themselves… in a way it’s very clever. But it’s just a gimmick.”

We concluded by talking about what single photograph he would take if it could be shown to the entire world, and Mankowitz’s answer reveals the humanitarian core of his artistic vision. “It would have to be something to do with peace,” he muses. “We live in such a confused, difficult and divisive time… I would try and create an image that would bring people together.”Today, Mankowitz’s work can be viewed at the Iconic Images Gallery in London, where examples of his photography are always on display. His latest publication, “The Rolling Stones Rare & Unseen”, offers an intimate glimpse into his extensive archive of one of rock’s most legendary bands. He is currently working on a new career retrospective, to be published in spring 2026.