This year, with the inaugural Blackwell’s Short Story Prize, Cherwell aimed to reconnect with its roots as a literary magazine in the 1920s, when our undergraduate contributors (including Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, and W.H. Auden) showcased the best of Oxford’s creative talent. We received nearly 30 entries, and they were all of an exceptionally high standard. The judge Dr Clare Morgan, Course Director of the MSt Creative Writing at Oxford, offered her congratulations to the shortlisted entries, including this one.

At the base of East Gate, on the High, rests a broken man. He is illiterate, but quite the talker. I, however, am a talented writer, if I do say so myself. Oxford educated, although I wasn’t always the most studious. But I’m as qualified as any to put pen to paper, and he asked me to tell his story. Destroyed as he is, brain totally scrambled, he can barely scrape his thoughts into order, but he told me his tale in splishes and splashes. Allons-y!

The poor man is in tremendous pain, unlike anything you or I could comprehend. It’s hot, strangely metallic, and so agonising that he thinks nothing could ever be worse. And nothing is, until the next moment, and the next, and the next.

He feels cold, too, frozen from deep within his gooey insides. It’s a wonder he remains in the liquid state in the winter months. A dribble of remaining spirit must be enough to keep him animate, and warm.

Above all, though, he’s lonely. He has no family, no friends. At first, locals came and tried to squeeze him back together; they scraped his guts back inside of him and bundled him up in Sellotape until he was fully mummified and practically spherical. Once term started, student activist types had all sorts of theories of how to fix him, but their theories lacked practicality, of course. Dreaming spires, sure, but not one person in this majestic city could put a man back together. After all sorts of city planning debates, it was decided he would remain in place.

Remembering the worst of it can’t help him now, so he stares, unblinkingly, into the sky (which you can never quite have looked at enough). The High has plenty to distract him: twinkling bike bells, the inane chatter of young lovers, the smell of food, the clamour of Covered Market sellers. And people avoid stepping on him, for the most part. He cherishes the promise of summer, some warmth to thaw the frost on his shell. Generally, adults avoid him (out of sight, out of mind), students sometimes say hello, but the little ones from the local school come and peer at him, and engage in small talk.

“It was nice,” he gurgled to me one morning.

“Nice?” I asked.

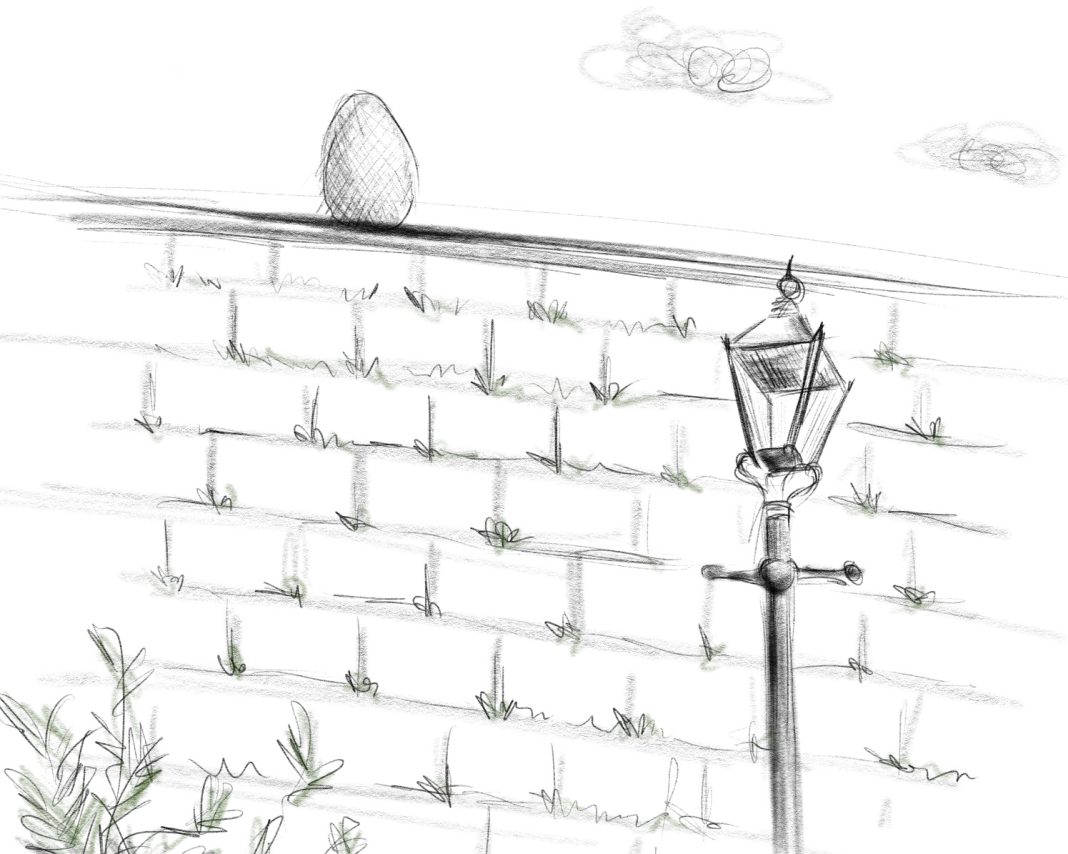

“It was nice,” he clarified, “Up on the wall.” He could see the whole city in its glory, sprawling and crawling wider by the minute. The evening light was bright in his eyes, but turned the Oxford stone golden, and gave the Church spire a long, spindly shadow which looked almost like a man, he thought. He looked down on the tiny townsfolk, going about their days like robots, with a sense that he ruled the world, perched above it all as he was.

And they really did try to help, when he fell. When he tumbled all the way from the top of the city wall to its bottom, where he went, for lack of a better word, SPLAT!

Humpty Dumpty can’t really move, and so he remains, still, after all this time, at the base of the high stone wall, which stands as an unpleasant reminder of his hubris (and a useful protective barrier on windy days). He doesn’t feel abandoned exactly, but he does feel forgotten; on top of the wall, he had dreams, and the fall woke him up in the middle of a really good one.

I don’t enjoy telling you all of this, but Old Humpty asked me to. I went to visit him for a final time a few weeks ago. I was his first visitor in months, he said, although he admitted that he loses track of time sometimes. He’s not much, anymore: little of the yolk and white remain, and the stone beneath him is discoloured, a mark of where he’s begun to decompose. But he’s still recognisably him.

An eggshell, almost pure calcium carbonate, will take a long time to biodegrade. When he asked me, “How long do I have?” I told him I did not know. I wanted to console him, but I didn’t know what to say. I’ve never liked talking to the dying.

Over the course of my shamefully infrequent visits, Humpty shared with me his past and his present, which I have told to you in its entirety. His future, I knew, was up to me.

I went to three Colleges before one took the bait, and agreed to fund some sort of memorial for the rotting man on the High. The Master suggested a statue could be placed by his body, I whiningly pushed for Radcliffe Square, but Humpty, wheezing in my ear, asked us to place his likeness on top of the wall, where he sat on that damning day.

And so, a bronze egg sits on a City wall, directly above the decaying man it was built for. The locals have come up with a rhyme about him, inspired by the imposing figure which shines orange at sunset.

I don’t know it exactly – something about the wall, the fall, the horses and men, back together again. It’s just a brief little ditty, quite light-hearted, for the children. It makes Humpty happy, so I approve, of course. Perhaps you’ve heard it.

Winner: “The Ghosts She Felt Acutely” by Polina Kim

Runner-up: “Letter from the Orient” by Dara Mohd

Shortlisted entries:

- “A Short Sharp Shock to the Skull” by Jim Weinstein (pseudonym)

- “Rhonda May” by Matt Unwin

- “Any Blue Will Do” by Kyla Murray

- “SPLAT!” by Sophie Lyne