The Oxford Literary Festival is one of those events I hear about every year, mark out on my calendar, and never end up going to. Sometimes it’s the distance that’s daunting, other times, it’s the difficulty of traversing the Circle line, finding a hotel without taking out a small loan, and spending between £8 and £10 pounds on every talk. None are insurmountable boundaries, but all kept me from the festival until this year.

A brief background: after hearing a hundred times that volunteering at the festival would be a great way to get involved in the literary world by every careers advisor under the sun, I caved and emailed the lovely volunteer coordinator. The process was surprisingly easy – after signing a document swearing I’d read and understood all the health and safety jargon, I was sent a schedule and a TicketSource login.

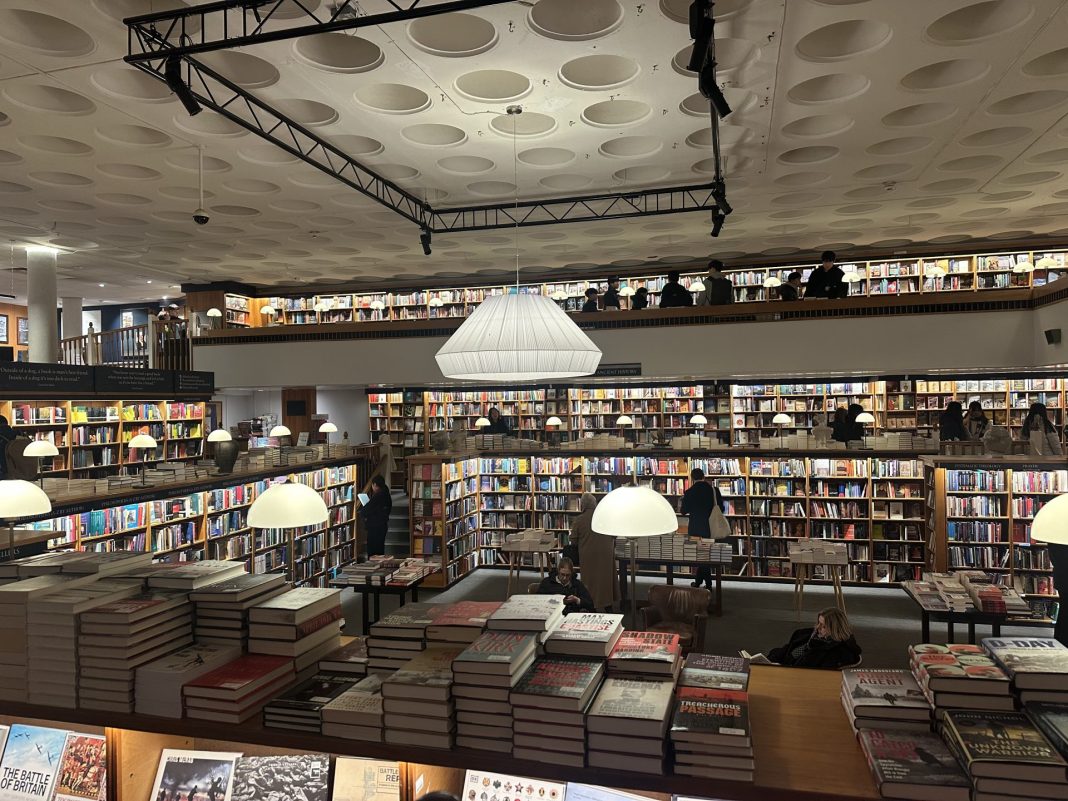

The great advantage of being a volunteer, is that I was able to get free access to any talk, provided I was not: a) on dreaded mic duty or b) stationed 20 minutes away from the centre. This led me to be privy to a great many talks I wouldn’t have otherwise attended: including Alexander Armstrong debuting his new children’s book (my Pointless-watching mother green with envy), Bettany Hughes who almost inspired me to become an archeologist and go crawling under the pyramids (she’s just that good of a speaker), and Abdulrazak Gurnah, discussing his latest novel (a trip to Blackwells thus ensued).

A stand-out was Wendy Cope’s talk – the poet being a favourite of both my sister and my grandmother, the former lucky enough to join me. Or perhaps I should say I was lucky enough to be with my sister. We had planned to go months in advance, and my sister became the first person to show Cope an ‘Orange’-inspired tattoo, and then promptly ordered me to take a picture of the two of them (with Cope’s permission). During the talk and then the follow up Q&A session, Cope presented reading and writing as entwined acts. While this isn’t necessarily a surprise, it’s always something of a revelation to think of one’s favourite author as a hunched-over, insatiable reader. After seeing only the finished products, the shining magnum opuses, it’s always somewhat unsettling to think of drafts and revisions. What writer wants to confront the fact that the first draft is never actually as perfect as hoped.

She told us, when asked what advice to give a young poet, that if you don’t love reading poetry, there’s no point in trying to write it.

While the advice, ‘if you want to write, read’, is nothing new, I’m always interested in examining how much it is followed. My go-to when faced with writer’s block is usually to take a stroll around the block. This allows me to let my mind free itself from the imaginary blocks I have constructed, or silence the whispering doubts. I don’t usually pick up a volume of poetry and fish for inspiration – I’m too afraid of plagiarism.

But similar advice is also given by Armstrong, to a chorus of bouncing children, hands reaching for the sky when he asks: “Who here wants to be a writer?”

His book Evenfall focused on the art and intricacies of perception, and thinking deeply about the world, it is in many ways a how-to for both reading and experiencing. A level of participation is required; one must prepare oneself to be immersed in a text – to be challenged and troubled. As much as life is pain, so is reading. The best works of literature do exactly this; they unsettle and confound and elude, all the while providing some essential nourishment, some deep teaching unbeknownst to the people we were before we turned the pages.

Cope enforces this – she tells us (a much more varied crowd in terms of age, than that of Armstrong,) that strong emotions equal true words. For me, that’s the core of poetry. With so few words, each one must count, and how better to pack a poem with evocative power than to mean something when writing it. In a new wave of anti-intellectualism and AI-generated art, we seem to have forgotten that literature is deep and rich in meaning – what we get out of it, what is put into it.

Writing and reading go hand in hand – as we seek out meaning in books and poetry, we fine tune our ability to create it with our own language, channeling emotion into beautiful and evocative words which ring true, and with depth.

Writing – and reading – for Armstrong and Cope, and even for Bettany Hughes and Abdulrazak Gurnah, is a deep engagement in real life. Something which, while often funny, is deeply serious too. I find this is best demonstrated in ‘The Orange’ where Cope leaves the reader with the poignant ending, “I love you. I’m glad I exist.”

Cope also ensures she leaves us with the fact that all her poems are serious: that even if they are humorous, or about the more trivial matters in life, they are not light verse. This concept is shown in ‘Some More Light Verse’, which discusses the experience of depression. The message is one of hope: “You have to try.” Hope perseveres throughout Cope’s oeuvres: hope in the small joys and moments of bliss; hope through the difficulties and trials of life. Both are presented by Cope as worthy of equal consideration.

The simple joys are often the best – the warmth of sharing food, of an inside joke, of a sunny morning. These things are serious, too. These things are worthy of poems, of commemoration, of being framed and mounted on an office wall. The act of going to a festival lecture and leaving, reminded me of joy. On the train home, I read my sister’s copy of Two Cures for Love. She borrows Richard II. The sunlight catches on my bracelets. I think, “I love you. I’m glad I exist.”