Common Ground, a café and community hub at the heart of Little Clarendon Street, is – as its name suggests – one of the few remaining places in Oxford that brings together both town and gown. Yet its future remains uncertain as Oxford University’s plans to redevelop its administration offices on 25 Wellington Square would mean Common Ground losing the building that it currently calls home. Located behind the offices, in one of the shop units leased by the University, Common Ground moved into a space, formerly a Barclays bank, that had been unoccupied for several years.

Common Ground was founded in 2018 by Jake Bacchus, a visiting senior member of Linacre College and Piotr Drabik, a barista and coffee machine mechanic. Bacchus and Drabik had a vision of creating something Oxford notably lacks – third spaces, away from home and work where people can spend time and socialise for free.

Primarily a café and co-working space, Common Ground is often bustling with students and locals working on their laptops, surrounded by an eclectic mix of furniture and art. It also houses second-hand clothing, book, and record shops, and plays host to live music, comedy nights, life-drawing, running clubs, student magazine launches, and a range of other events that would take the length of a second article to cover.

The new plan for Wellington Square

The proposed plans for the redevelopment of Wellington Square were first made public by Oxford University Development (OUD) in October 2024, citing the need “to replace a life-expired and poor performing building”.

Divided into two phases, the first phase would involve the demolition of 25 Wellington Square, a concrete brutalist building that stretches the length of Little Clarendon Street and is home to Common Ground. 25 Wellington Square will then be replaced by “a brand-new state of the art academic facility” which will accommodate “existing university departments that need to be relocated from elsewhere in Oxford”.

Plans for a “publicly accessible café” are included in the design. However, it is not clear if Common Ground will be permitted to occupy this space in the future, or indeed if it will be able to, after having to relocate for three years during the building’s construction, which would begin in 2026.

The second phase of the redevelopment would consist of the refurbishment of the western terraced houses bordering the square, which would create 100 new rooms of graduate accommodation.

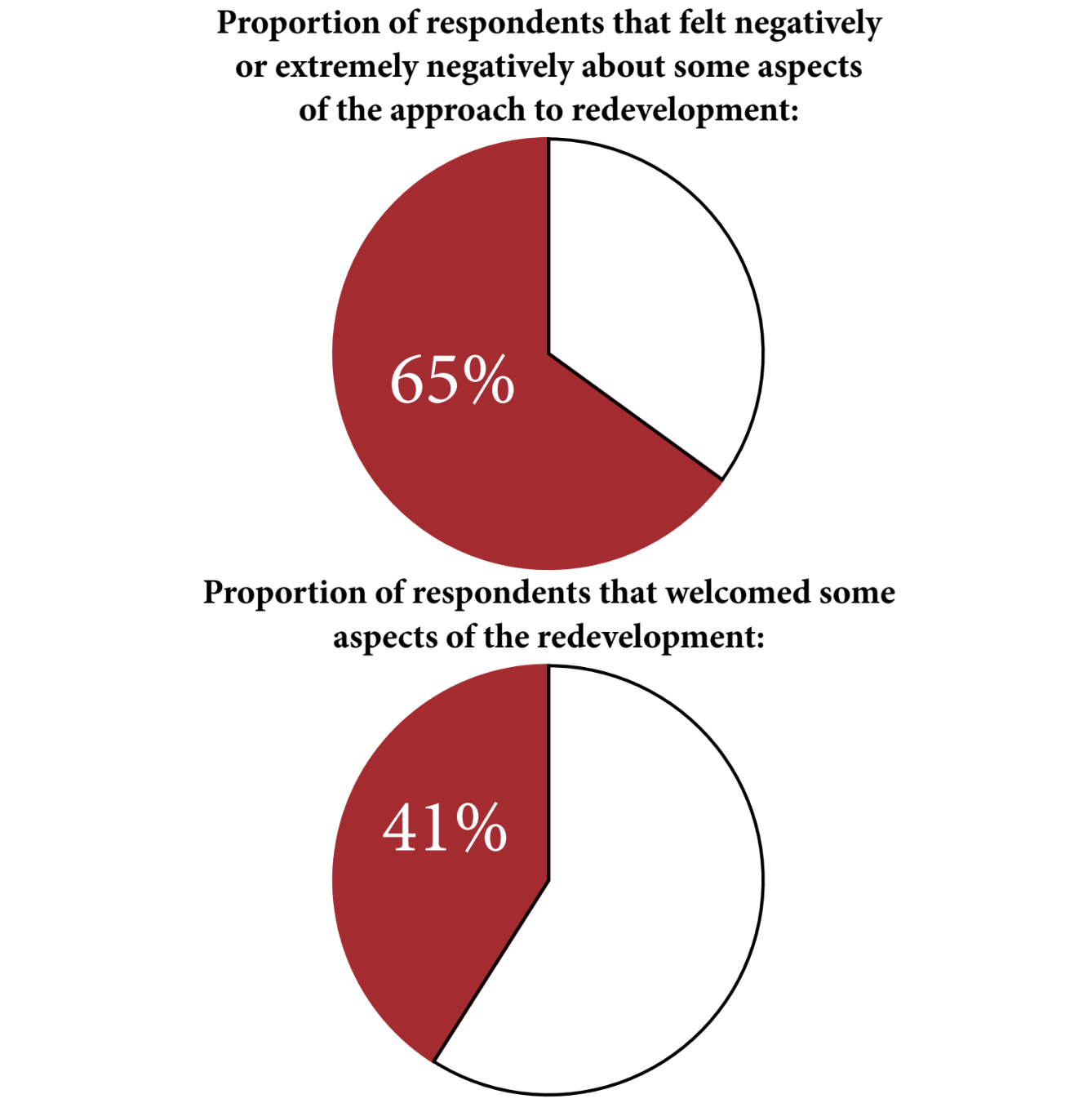

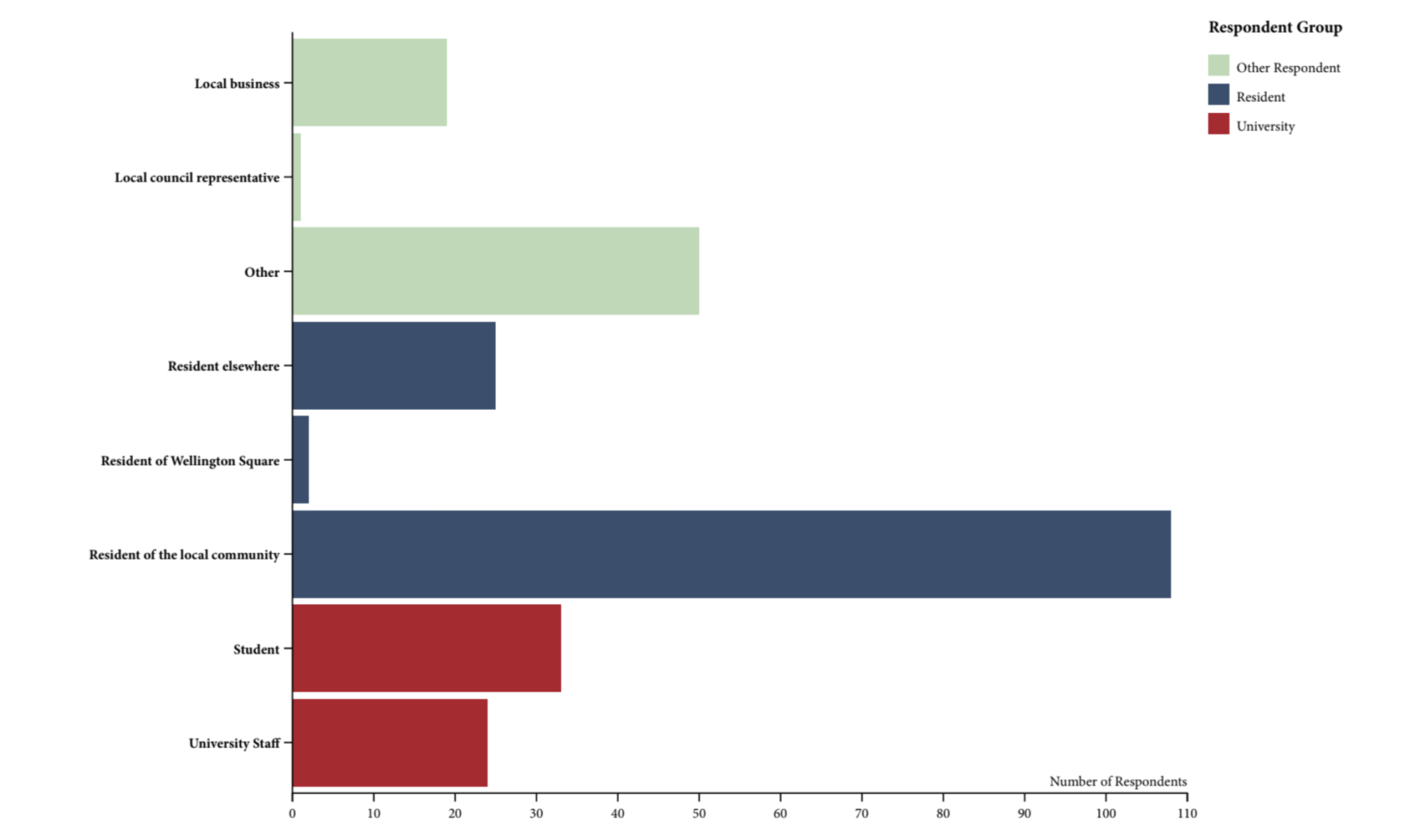

In December, OUD held its first public consultation on the plans, which gathered responses from the public, showing that nearly two-thirds of respondents felt negatively towards some aspects of the redevelopment. The most popular aspect of the redevelopment was the energy and sustainability of the new building. Over 64% of respondents raised concern about “the risk to Common Ground, viewed as a vital community hub and cultural venue, one of few remaining in the city.”

Images Credit: Oscar Reynolds for Cherwell

(This is a limited sample, likely unrepresentative of the Oxford community).

Common Ground responds

Cherwell spoke with Common Ground’s Managing Director Eddie Whittingham and Operations Manager Alex Chesters about Common Ground’s role in Oxford.

Chesters told Cherwell: “It’s huge that this is a place right now where anyone from any walk of life – students or professionals or even homeless people – can come in and just chat to someone who works here and everyone is treated the same and everyone gets the same coffee and the same level of care. And in a place like Oxford where so much of it is closed off and only students can go in those parts.”

Whittingham agreed, adding: “I think hosting a whole range of different things means that the town and gown can mesh a lot more easily. If a student comes to see their mate play in a band, they might think, ‘well what other gigs have they got on? Oh, there’s this other gig that has been organized by Divine Schism, a local promoter.’ And they come back into the space.”

Chesters told Cherwell: “During the first [OUD] consultation, we were packed for the whole day. And since then, we pretty much at least once a day have someone come up and ask when they get a coffee, what’s going on? Have we heard anything else? It’s very few spaces that people feel so passionately about and are so invested in.”

When focusing on their interactions with the University, Whittingham stressed that University leadership had been receptive to some of their ideas and was hopeful that an agreement between the sides could be reached. They hope to be able to move into a University or college-owned space, and perhaps act as a channel for the University’s community engagement in the long-term.

What began as responses to the OUD’s consultation questionnaire quickly became personal testimonials on the importance of Common Ground to both students and locals alike.

To Daria Tkachenko, who came to Oxford as a refugee from Ukraine three years ago, Common Ground is “a community that accepted me with open arms. It’s a reminder of what home can feel like, even in the most uncertain of times.”

One student told Cherwell: “As someone who grew up in Oxford, I have been going to Common Ground long before I was accepted into the University. It would be a terrible loss; it’s somewhere I go all the time in the vac to study with friends who come back home from other unis and can’t access the libraries here.”

Developments in town vs gown

The divisions between town and gown are a well-documented part of the city’s history, with disputes between townspeople and members of the university leading several scholars to flee Oxford and found that other university in 1209.

In more recent times there have been a series of disagreements between residents and the University over the approach to urban planning.

In 2016 the University’s sale of its Wolvercote Paper Mill site caused criticism from residents when it rejected a bid by Homes for Oxford, an alliance of community-led housing groups, focused on affordable housing and instead sold it to the highest bidder, a private developer called CALA.

Another such example was the former Volkswagen garage owned by Wadham College, which was occupied by squatters for two months in 2017, driven by their desperation for shelter and wanting to draw focus to the inequalities in the city. Despite protest action from locals and students, the college evicted the largely homeless group in the middle of winter and proceeded to begin development of student accommodation on the site.

Earlier this year plans for new Magdalene accommodation on its Waynflete site, situated beside the Cowley roundabout, has also garnered complaints from residents.

As by far the largest landlord in Oxford, the University has disproportionate influence over determining the building and future of the city.

An investigation by the Guardian in 2018 revealed that Oxford and Cambridge colleges combined own more land than the Church of England, making them the largest private landowners in England.

Developments are always needed, especially in a dynamic and changing city like Oxford – or as the OUD’s Wellington Square redevelopment poster put it: “Modern facilities are essential to attract and retain staff and students in a highly competitive academic world.” New housing developments are especially pressing, given that Oxfordshire is at the centre of Britain’s housing crisis and has fallen badly short of its government-mandated building targets.

The plans for the redevelopment emphasise the increased sustainability and energy efficiency of the new building. For phase two, the 100 new graduate rooms will be important “in helping to reduce pressure on private rentals” and aim to improve housing affordability in the city.

Such tensions show that there is no perfect answer in how to prioritise the needs of different parts of the Oxford community.

With the newly created role of Local and Global Engagement officer in 2023, perhaps the university is beginning to turn a corner in its relationship with Oxford residents. A report published in January, ‘Beyond Town and Gown’, outlines the University’s “plans to support positive social, economic and environmental change in the city”.

Both the city and the University are dependent on one another to function, and are most effective when they work cooperatively. As students we hold a privileged position, although most of us are only in Oxford for half the year, with our Bod cards we have access to much of the city that remains closed off to people who have spent their entire lives here. Unrestricted spaces like Common Ground, where town and gown can meet, are special. A more modern, efficient building with additional housing would be a good thing. But, with the University having outlined a mission to integrate more meaningfully with the local community, its ability to preserve spaces like Common Ground will be a litmus test for that commitment.