Cherwell: What was your experience like as a woman at Oxford in the 1950s?

Hoskyns: Well, I was there from 1953-56 and they did have women students, so we were quite privileged. I was at St. Hilda’s, and there were I think four women’s colleges, but it was a kind of carved-out space for women in a male dominated world. We went to lectures with male students and I had some tutorial sessions with C.S. Lewis. He was a very strange person. He was very monosyllabic. He wasn’t at all chatty. The women’s colleges were separate and we were locked in about 10 o’clock, but there was a lot of climbing over the walls, in both directions. And a friend of mine actually got a key cut to the side door. That was useful. There was a bit of intermingling, as you might expect.

Cherwell: You worked at Cherwell at university – what was your experience like with that?

Hoskyns: I was the film and theatre critic and reviews editor. There was a really funny occasion where I got what I thought was a very good review of a book and I wanted to put it in full, but there wasn’t enough space. So I left out the cinema times – we had what the different cinemas were showing, and I left that out in order to include this review in full. And the editor sent for me and he said, never do that again. He said, don’t you realise people only read the paper to see what’s on at the cinema? They don’t really read it for these intellectual reviews and so on.

Cherwell: Moving beyond your time at university, you worked for a long time as a journalist. Could you tell us about that?

Hoskyns: Well, I went to Africa because I got interested in Kenya (a British colony) while I was at Oxford and soon after. Kenya was in a real crisis then because of the Mau Mau rebellion – there was a revolt among the Kikuyu tribe, which was very violent and was repressed with extreme violence by the British.

The British army was out there, but there was a lot of sympathy for the Kikuyu in other areas because they’d been so severely repressed. They couldn’t grow cash crops. They were very poorly paid. They’d been excluded from their land, so they were often working as labour on territory that they thought was theirs. And they were given no representation, and nobody would listen to them. So they took to violence in order to make a point. And a number of white settlers were killed, farms were destroyed. And then it was repressed by the British.

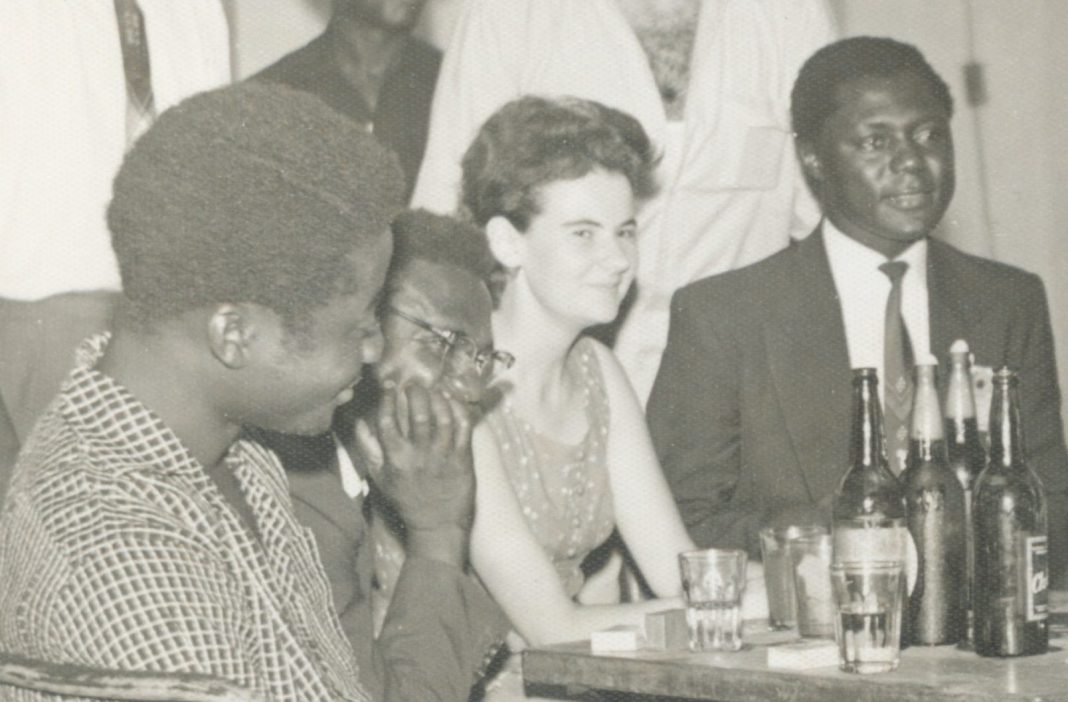

So when I came out, that was more or less finished, but the question was what to do. And it was clear that the British had to give some representation to Africans. They couldn’t just go on treating them as slaves and giving them no possibility of political or legal action. And so I came in just that stage when other African politicians were beginning to emerge and when it was agreed that there would be some African representation in the legislative assembly, and there would be elections.

So it was quite an exciting time to come. I got a job on a paper called The Colonial Times, which sounded very right wing, but it was actually an Asian paper, which was quite radical. It was run by a Gujarati family, and had had a tradition of siding with the Africans against the British.

Cherwell: You have also worked as an academic on the evaluation of women’s unpaid work.

Hoskyns: Yes, that’s right. My nephew Nicky was working in the cooperatives in Nicaragua and when I visited, I think in 2010, we got The Body Shop to actually include a component for the women’s unpaid work in the cooperative as one of the costs of producing sesame. I think this issue is a good one to take up as a feminist, the unpaid work that women do, which is not counted or valued. It’s actually a subsidy to capitalism.

But that was a bit later. I became a feminist because of having a baby and being cut out and being treated as a non-person. My daughter was born in 1968, and the early seventies were a time when feminism was really taking off and a lot of small groups were formed. And I was at a very famous conference in Oxford held first in Ruskin College and then in the Oxford Union – it was the first National Women’s Liberation conference. That was very energizing. When I was at Oxford as a student, women weren’t allowed to be members of the Union.