You’re sat in the Rad Cam. It’s week five of Michaelmas. You’re hunched over, squinting through the dim yellow light to make out the arguments of a particularly dense reading on the Catholic Reformation. For the sake of pathetic fallacy, let’s say that a pitiable spattering of rain is pattering against the windows as a librarian-cum -bouncer kicks out the 37th tourist trying to enter their well-guarded sanctuary in the past hour. Sifting through the page’s thickets of doctrinal details, you notice a comment, pencilled into the margins:

‘I really want a hard fuck…’

It is accompanied by a small sketch.

You might stifle a chuckle, add your own contributions, shake your head with dismay at the defacement of library property, or simply continue to stare blankly at the page as you have been doing for the past hour. But, whatever your reaction, it makes you pause. When I found myself in this exact situation, the pause sparked a question. How can marginalia provide an insight into the psychology of the Oxford Student?

As long as written texts have existed, so has marginalia (I have no proof of this, but it seems logical). Historians are particularly fond of using the bizarre marginalia of medieval European manuscripts to understand the peculiar mindscapes of the monks that copied them. Some bear striking resemblances to the marginalia created by 21st-century Oxford students. I think we can all sympathise with the burnt-out monks who felt the need to scribble on their handiwork that “writing is excessive drudgery” and, presumably nearing the end of their task, “the work is written master, give me a drink”. Other examples of medieval marginalia pose a somewhat greater interpretative challenge. Take, for example, this thought-provoking illustration of a nun harvesting penises from a thriving penis tree.

Other highlights include monkeys playing the violin, knights battling snails, a rabbit beating up a man, a woman riding a phallic-shaped green monster, and a king doing his business on a couple making out. Let psychologists and historians make of that what they will.

So what did my deep dive into the nether regions of the Facebook page ‘Oxford University Marginalia’ (yes – it’s a thing and there are 11,700 members) reveal?

Unsurprisingly, just like with the medieval monks, a fair amount of our marginalia relates to sex and genitals. Few, however, are as direct as the plea for a ‘hard fuck’. Many go for a simpler, yet still elegant, approach. One student adorned a passage on military history with one word, ‘BALLS’, emphasising their statement with a sketch.

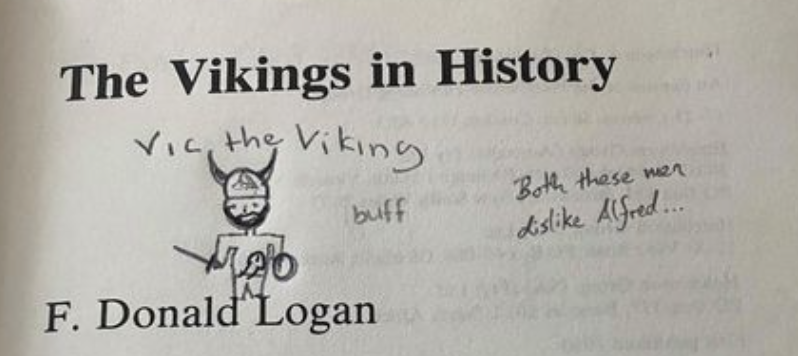

Indeed, genitalia abound in Oxford’s marginalia scene, my personal favourite being the masterpiece that is Vic the Viking (see below). Some marginalia adopt an almost interactive approach, with another student leaving a lipstick imprint at the bottom of a page of literary criticism. This incited a spate of considered responses, including ‘mmm…. You are a sexy lady’ and ‘lol’.

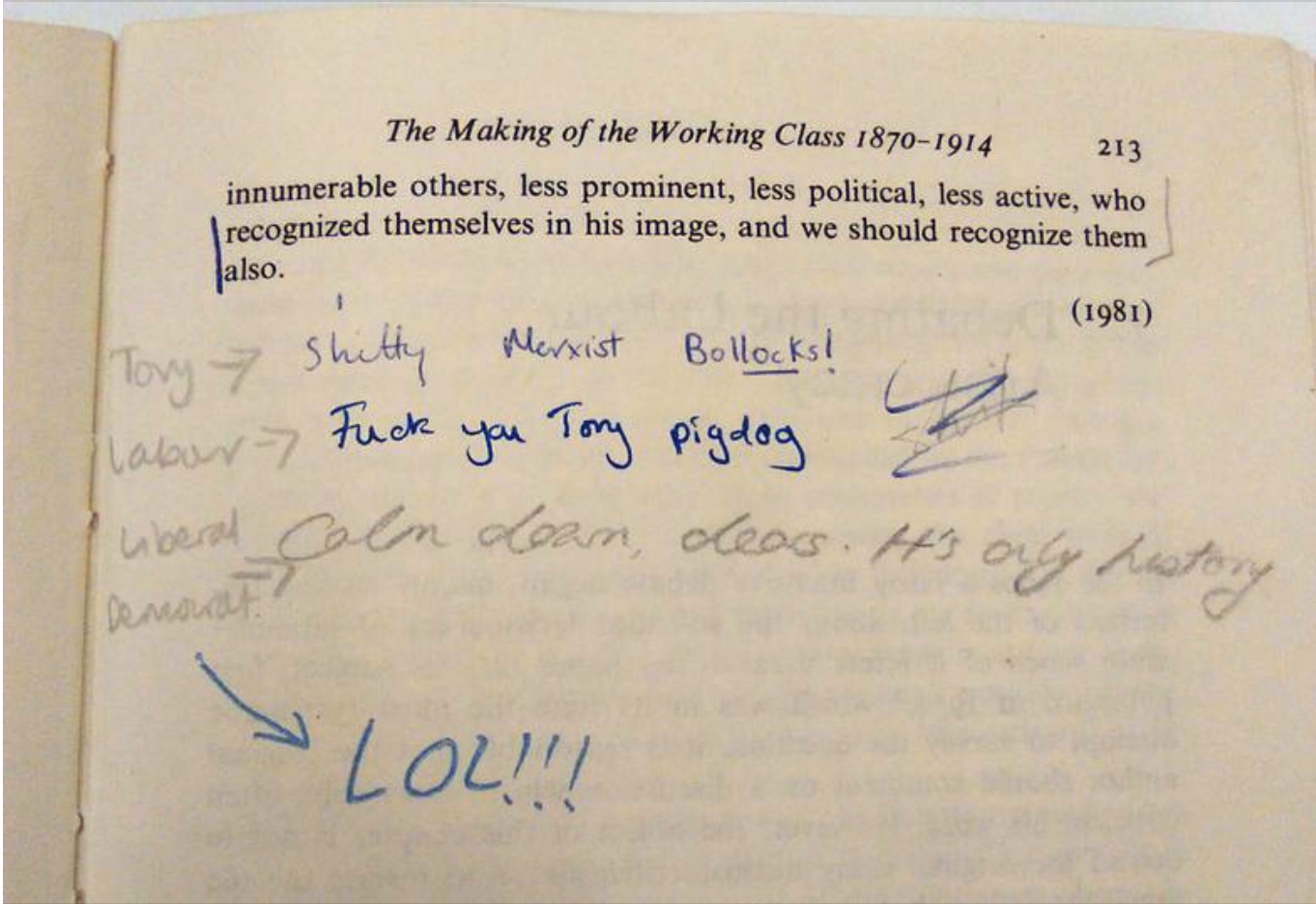

But it’s not all sex. The margins of Oxford’s books are the battleground for opposing troops of dedicated political partisans. Take, for instance, the marginali-er who expressed their utter contempt for socialism, by annotating a copy of the Marxist historian, Eric Hobsbawm’s, book. They composed a fairly lengthy argument stating, amongst other things, that ‘this book is written by a deluded Marxist in denial of socialism’s death in 1989/91’ and that ‘his beef with capitalism is pathetic’. This political polemic did not go under the radar, with another comment responding that ‘it’s 2019 and socialism is more alive than ever’. As you might expect, however, the political debates etched into Oxford’s books often play out in a slightly less eloquent way. In a copy of E.P. Thompson’s The Making of the Working Class one student expressed their opinion that it was ‘Shitty Marxist Bollocks!’, to which a differently-inclined student replied ‘Fuck you Tory pigdog ’. A third implored the combatants to ‘calm down, dears. It’s only history’.

Another unflattering insight into the psyche of the Oxford Student provided by marginalia is the strain of deeply rooted pedanticism. Take the student from the 1700-or-1800s who inscribed on the final page of Paradise Lost that “the poem [would have] ended better if the two last lines with my slight alteration … preceded the two before them”, or their modern-day counterparts who argue over grammar and etch the words “wrong”, and “pile of shite” into the margins. It seems that many Oxford students cannot seem to resist asserting their intellectual superiority for subsequent readers to witness. This has sprouted an amusing counter-genre of marginalia. Some of my favourite examples include whichever quick-witted reader replied to a comment that a book was making a “stupid assertion”, by applying that epithet to the commenter themselves: “ur a stupid assertion”, and the evidently fed-up individual who instructed a particularly pedantic commentator writing in red pen to “piss off you red bastard”. In fact, irritation, confusion, exhaustion, and despair dominate Oxford’s marginalia scene. Many examples lament the monotony of the reading material, exclaiming things to the tune of “why the fuck is this all so boring”. Others have a more personal focus. One of my own finds involved a sleep-deprived student claiming that a suspicious-looking stain on the page was “clearly wept from my blood-shot eyes as I pull my 4th all-nighter in a row”.

Having explored the darker sides of Oxford’s marginalia, it’s important to remember that not all the marginalia is so bleak. You can also find the effusive soul who found a footnote citing a work by a certain K. Minogue in a book on twentieth-century British liberalism and offered her congratulations, “well done Kylie!”. Or another who noticed a crucial omission in the dedication of the book they were reading, amending it to read, “for Jerry: teacher, mentor, comrade, friend, mouse”. Others generously share thought-provoking insights, such as one commenter on Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble who threw this question out into the universe: “do you ever just sit down and look at yourself and realise, I’ve been eating chicken titties all my life”. So we can rest easy in the knowledge that not all Oxford Students are sex-obsessed, arrogant, sleep-deprived, political fanatics.

But what’s really going on when we write marginalia? Many educationalists believe that marking up the books we’re reading helps us think critically, absorb the material and generally stay awake. I can understand where they’re coming from, but I think, based on absolutely no knowledge of psychology, that there’s more to it than that.

In some cases, it feels like the scholarly equivalent of peeing to mark your territory. There’s something weirdly satisfying about the thought that you’re making some kind of connection to the random series of strangers who pick up the book next. I think it’s also a testament to the capacity of our brains to engineer amusement when they are bored, and perhaps to a certain well-intentioned aim to make the next reader have a little chuckle. Of course, it’s never the best idea to damage public property (in fact, it could land you with a hefty fine), and subsequent readers might find marginalia extremely distracting. But as far as the already extant marginalia goes, you might find that stumbling upon it’ll brighten up your day and reassure you that you’re not the only one finding that particular reading a Sisyphean slog.