Victories for the far-right no longer shock us, but we cannot normalise this upending of the post-war political settlement.

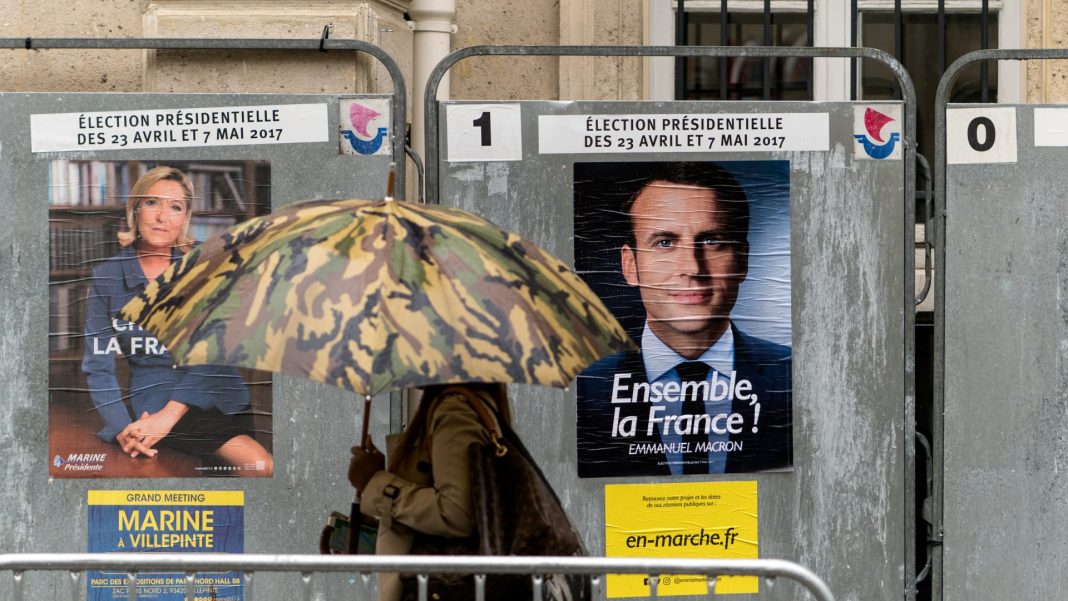

The European Parliament, founded to foster peaceful cooperation, has seen far-right parties make considerable gains in recent decades. While the far-right obtained mixed results in the most recent EU election, in Europe’s most powerful countries, they won historic mandates. Nowhere was this felt more keenly than in France, where half of voters opted for parties on the ideological extremes. Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (RN) won more than 31% of the vote, over twice that of Emmanuel Macron’s Renaissance party. Then came the French president’s coup de théâtre, a shocking announcement to dissolve the National Assembly and return power to the people. The time has come for French voters to decide whether they truly want a far-right government.

Macron has always been a political disruptor. His centrist political movement obliterated France’s traditional parties, inadvertently rendering the Rassemblement National the de facto opposition. But even for Macron, this is bold and incredibly risky. He’s in a game of 4D chess, and he might have just played the Von Papen gambit – all but inviting the far-right into government simply because they might be weaker inside the political fray. Infamously, the move did not work out for that particular German chancellor, but at least Macron has decided to take on his far-right opposition directly, which is more than can be said for many moderates across Europe.

Jordan Bardella, Le Pen’s 28-year-old charismatic protégé, is charged with leading her party to victory in the parliamentary elections. A digital native with over 1.6 million followers on TikTok, Bardella has proved extremely popular with the disaffected youth of France. Despite having little political experience, a third of people aged 18-34 voted for the RN in the EU election. For Macron’s Renaissance party, it was just 5%. While many of those who abstained from the EU elections are sympathetic to the RN’s anti-institutional stance, Macron is banking on the electorate not casting protest votes in a crucial domestic election. Macron’s approval ratings are incredibly low, having hovered around the low thirties for months. For Bardella to succeed in becoming prime minister, it would destroy whatever remains of the once ironclad cordon sanitaire. Jacques Chirac famously refused to debate Jean-Marie Le Pen for the presidency back in 2002, deeming it beyond the pale. Yet this week, Éric Ciotti, the current leader of Chirac’s old centre-right group, Les Républicans, set off a civil war in his ranks by announcing his intention to ally with the far-right. Macron accused Ciotti of making a pact with the devil, and his colleagues moved to oust him from the party.

Macron, for his part, likely believes that he has made an astute political manoeuvre. By surprising the fractured left with a snap election, Macron has made their herculean task to cobble together a functional alliance even more difficult. While the Socialists performed relatively well in the EU elections, closely trailing Macron (and considerably improving on their cataclysmic results in the 2022 presidential election), they will be forced to work with Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the controversial firebrand from La France Insoumise who narrowly missed out on the second round of the presidential election due to disunity on the left. The ideological tussle is already problematic enough before you throw the Communists and Greens into the mix. Thus, Macron is hoping to pick up reluctant left-wing voters, forced to choose between centrist and far-right candidates in the second round of voting, when all but the top two parties have already been eliminated. Macron used this recipe to win the presidency twice.

Macron lost his parliamentary majority back in 2022 and was likely already planning an election for later in the year. He has clearly calculated that any period of cohabitation (in which the government is led by a party different from that of the president) would be unlikely to make much difference to his frozen legislative ambitions. For their part, the RN would struggle to pass their domestic agenda, potentially paralysing their momentum in the lead-up to the 2027 presidential election – which Macron cannot participate in due to term limits. Ideally, Macron would like to claw back a parliamentary majority, but realistically, this political manoeuvring is to prevent a future President Le Pen.

Despite the high stakes, Macron is right to have taken a stand, to have refused to normalise the far-right when so many other moderate political parties have made dangerous, self-serving alliances. Given the balkanisation of far-right parties in the EU parliament, it is as important as ever to call out their ideological extremism. The Overton window has gradually shifted; extreme policies have become more mainstream, enabling some in the far-right to rehabilitate their image. Take Le Pen, who booted her father out of the party he once led and changed its name. She recently ejected the AFD, the main far-right party in Germany, from her faction in the EU parliament—Identity and Democracy—after the party’s leader defended members of the Nazi paramilitary group SS. By rendering the AFD “outcasts,” Le Pen positioned herself as the arbiter of acceptability. Giorgia Meloni, meanwhile, has been so successful in toning down her rhetoric on the international stage, working closely with the EU president Ursula von der Leyen, that commentators have started to overlook her party’s post-fascist roots. At least Macron refuses to follow this model of gradual acceptance, whereby moderate parties adopt the policies of the far-right to gain back disaffected voters, in the process becoming the very thing they vowed to destroy.

In such uncertain times, we need decisive leadership and the courage to take a stand. The popularity of the far-right represents a failure of moderate governance, and politicians need to take responsibility for that by charting a new path forward, bringing everyone in society with them. The politics of our age is governed by both emotion and apathy. We must not weaponise the former or fall victim to the latter. As Macron stated in his speech to the nation, it is better to write history than be its victim.