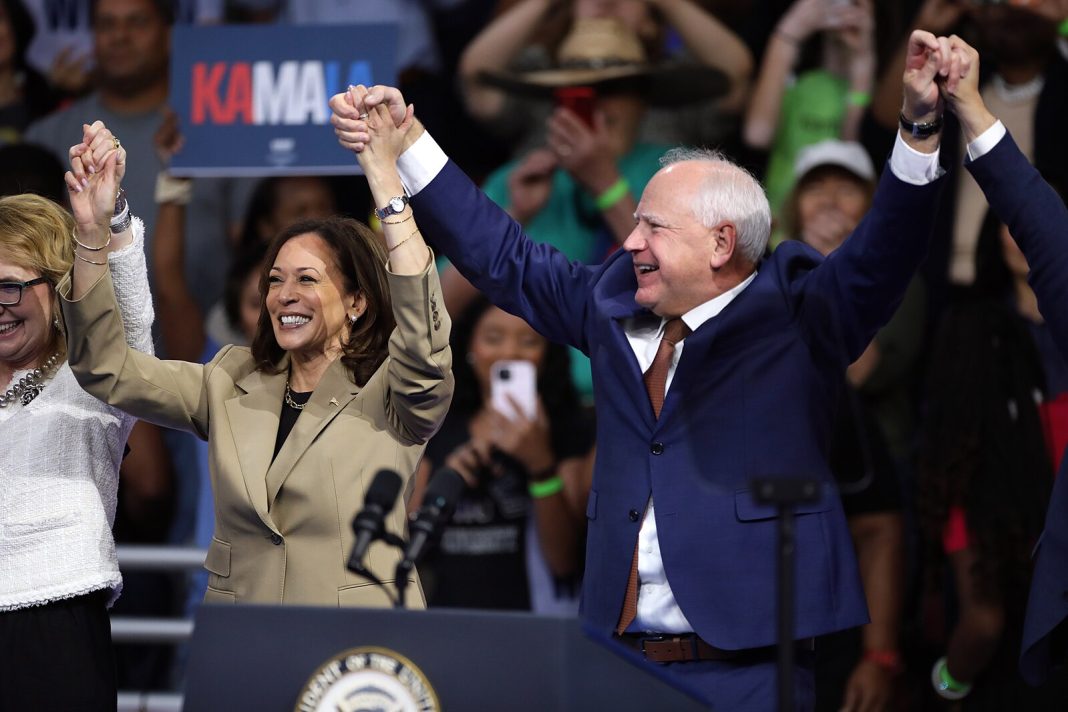

If there’s one word that Tim Walz emphasised on his first day as Kamala Harris’ running mate, it was “joy”. Since his selection, support for Walz has coalesced instantaneously among Democrats. From progressives like Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez to moderates like Joe Manchin, Walz has an uncanny ability to satisfy all aspects of the caucus. The party seems happy again, regaining a sense of optimism that had previously evaporated.

There’s little reticence concerning Walz. By all accounts, he’s a friendly and normal guy. In stark contrast to Donald Trump’s running mate, Walz looks completely at ease when delivering his stump speech. Watch JD Vance attempt the same, and you’ll see how his sloppy delivery of low-grade jokes fails to garner substantial laughter. Struggling to land punchlines, Vance becomes one himself, ridiculed and laughed at during Democrat rallies – much to the joy of party attendees.

The role of laughter seems more pronounced in this election than in previous ones. Whether it’s Harris’ cackle landing favour with Gen Z or Barack Obama’s penis-size joke at the DNC, there has been a definite shift in campaigning strategy. Michelle Obama famously said in 2016 that “when they go low, we go high” yet arguably, the Democrats have been beating the Republicans at their own game here. In part, this is a response to the dirtier and more insulting politics which Donald Trump popularised – yet there’s a fine line between the jokes deployed by Democrats as part of a campaigning offensive and those uttered by Trump which just are offensive.

Not everyone appreciates this distinction. When Democrats communicated the insensitivity of Trump’s remarks during the 2016 campaign, it seemed to fall on deaf ears. Many voters liked how he was a “straight talker” who “said it like it is”. They were attracted to his belittling of politicians because that’s how they felt about politicians too. Trump positioned himself as a spokesman for the people, someone who spoke their language and understood their concerns. He was down-to-earth and relatable, grounding his campaign in a motif of simplicity. If the Democrats are to win in 2024, then they need to battle the Republicans on these same terms.

This is why Harris’ pick of Walz is so astute. He can appeal to these voters. Even before his nomination, Walz had been criticising the political climate fostered by Donald Trump. In an interview on Morning Joe, Walz lamented how Americans now dread attending Thanksgiving dinner due to the inevitable political debates which emerge at the dinner table. These aren’t mere disputes anymore; Thanksgiving quarrels now serve as battlegrounds of morality. Being Team Red or Team Blue is no longer about your approach toward fiscal policy or political philosophy – it’s seen as a measure of your patriotism. Many Americans are sick of these culture wars and wedge issues, and Walz highlights how Trump continues to fuel them.

Bringing up a shared experience like Thanksgiving lethargy may seem like a relatively simple tactic, but simplicity resonates in election campaigns. It’s the currency of success with which Donald Trump won the presidency. Whereas Hillary Clinton proposed complex policy positions to the public, Trump latched onto headline-grabbing slogans such as “drain the swamp” and “make America great again”. Arenas full of people would chant them – smiles on their faces, joy in their hearts.

However, the joy found in Trump’s 2016 campaign wasn’t the hopeful and optimistic kind espoused by Desmond Tutu; it was joy at the expense of others. Joy at the expense of pollsters; joy at the expense of Clinton; and joy at the expense of sexual assault victims. In a sick perversion of the slogan, “#MeToo” went from a statement of solidarity to a swagger of success. For every woman whose “Me Too” meant that they, too, were victims, there was a man in the White House for whom it meant that he, too, got away with it. Pollsters, Clinton, and social movements all became part of an “elite” that had, for generations, let Middle America down. Feeding into feverish excitement, joy among Republicans only grew as polling day neared. Yet this was a joy that couldn’t exist in a vacuum since it was only alive by virtue of schismogenesis and division. Thus in 2016, the Republicans weren’t happy because they won – they were happy because the Democrats lost.

To some extent, this relativity of joy is present in the Harris/Walz campaign. Yes, there is genuine optimism for the ticket across the broad spectrum of the party but fundamentally, the Democrats fear what a second Trump Presidency would bring. The joy in their poll lead is exacerbated given that it’s Trump they’re defeating. Harris taps into this when she whips up the crowd into chanting, “we are not going back”. Although Clinton’s warnings about Trump in 2016 may have been prescient, they only fed into his argument that political elites were out to discredit him. Now, in a post-January 6th world, the terms of debate have shifted, with Harris’ message speaking to tangible concerns. The American people know what a Trump presidency looks like. They know how desperate he is to regain power. They know how little he cares about the country. This isn’t speculation anymore – it’s fact. It isn’t a message built from fear so much as one inherited from recent history.

How the Democrats tackle this fear is through joy. Not joy at the expense of others, but joy in the hope of a better tomorrow. Both Democrats and Republicans use the relativity of joy, but their foundations differ from being rooted in distinct policy platforms. With the Democrats offering social security and gun reform, the smiles at Harris/Walz rallies stem from the joy of providing. With the Republicans supporting a ban on abortions and restrictions on IVF, their cheers represent the joy of depriving. A clear faultline therefore emerges, with both campaigns fighting to win the monopoly for joy. At the minute, though, polling momentum points in just one direction – and it’s generosity which is on Kamala Harris’ side.