The romantic comedy genre is often criticised for its overreliance on tropes. The romcom is, after all by, designed to be light and fun. Though today we often take that to mean derivative and corny, entertaining has not always meant unserious. A genre that began with Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream must have more to it than the boy-meets-girl box office hits churned out today. ‘Golden age’ romcoms feel like a far cry from this year’s Anyone But You and The Idea of You. So, what’s changed?

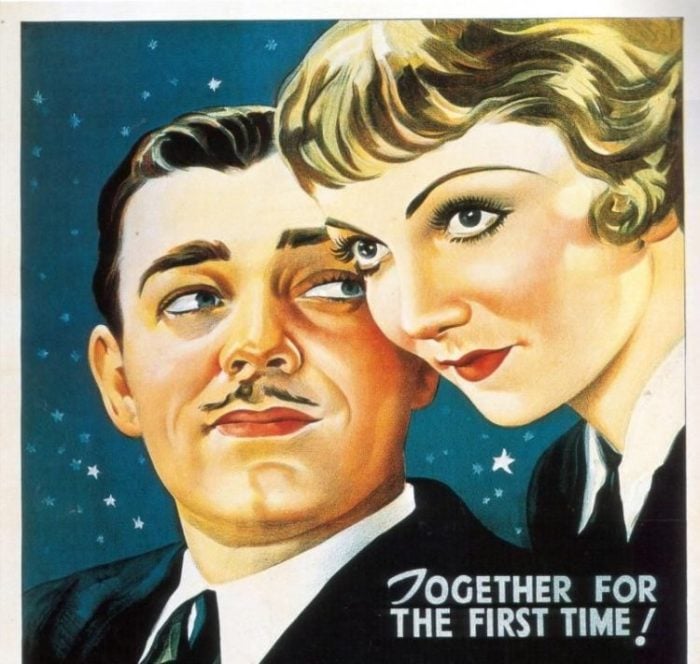

It is difficult to discuss the trajectory of the romantic comedy without first considering Frank Capra’s 1934 hit, It Happened One Night. The film follows a young heiress (Claudette Colbert) and an unemployed reporter (Clark Gable) who meet on a bus to New York. The plot features all sorts of scenarios that are very familiar: the begrudging allies-to-lovers arc, forced proximity, and the classic third act conflict. However, at the time of its release, the film was subject to a critical acclaim – alongside its box office popularity – that we don’t associate with the romcom nowadays. It was the first film to collect all five of the main Oscar awards. Not only does the 90-year-old film still feel fresh and charming, but it offers an impressive artistic insight beyond its entertainment factor.

The film’s shots are composed with a care and intricacy that is rare within contemporary big studio romances. The now famous ‘walls of Jericho’ scene is a prime example of this. Being forced to sleep in the same room, Gable hangs a blanket (the walls of Jericho) between him and Corbert. Not only does this highlight the tensions between them, but also reflects the tentative nature of their alliance. It is one of many similarly inspired moments, but the film is far from an escapist fantasy: class, the impacts of the Great Depression, and the divisions of 30s America underscore the plot, whilst still maintaining its lighter tone. Ultimately, It Happened One Night is a nuanced and character-focused film, in which we are given two flawed, three-dimensional human beings. This is not exclusive to It Happened One Night: later big studio films such as The Apartment, Roman Holiday and To Be or Not to Be – to name a few – have the same appeal.

In contrast, Anyone But You, released in late 2023, made headlines not by a sweep at the Oscars, but by turning over eight times its $25 million budget at the box office. The picture was hailed as the return of the romcom, with its director stating that the film was “the last romcom in the history of cinema and theatricality.”. But if Anyone But You is supposed to revive the romcom, then the genre is doomed. Visually, the film is stale: there are few memorable shots, and between Sydney Sweeney’s monotonal delivery and Glen Powell’s unexplained shirtlessness, the chemistry between the two leads is equally sparse. The main issue, however, lies with the script, which contains pearls such as: “Trust me, bro. We’re all in seventh grade when it comes to this stuff [love].” Bea (Sweeney) and Ben (Powell) are already, at best, thin characters, and are further let down by the seemingly interchangeable supporting cast. We watch as the plot jumps from gimmick to gimmick – she runs away before he can explain, fake-dating, an ex-lover returns to the picture – without any kind of natural flow. This film just isn’t interested in love and its nuances in the same way its predecessors were.

The difference, then, seems to lie in the modern approach to the genre and entertainment. At some point, the romantic comedy became less of a comedic exploration of love and human relationships and more about hedonistic fulfilment. In theory, perhaps there’s nothing wrong with this, but recently it has made much of mainstream, big-studio cinema deeply uninspiring. This isn’t to overly-romanticise the cinematic past, but there used to be space for films like It Happened One Night and The Apartment, which were extremely entertaining but also extremely well-crafted pieces of art. Increasingly we seem to want to separate entertainment from intellectual stimulation. But why can’t it be both? Why can’t we be entertained and provoked at the same time?