Internship pressure is intense in Oxford, but it’s not felt uniformly – demand is concentrated in a few select sectors which have been favoured by structural economic changes. Whilst some people love their weeks in the office, for many it’s just an endless stepping stone to the next thing.

With the sky outside already dark, the blue and white of the Oxford Careers Service lights up my room. I click on the box of another company’s advert, the name some grand stew of corporate words, the logo a rich green background with Times New Roman overlaid. A company description packed with superlatives, words like ‘dynamic’ and ‘delivery’, and some fluff about caring for employees and the future.

Lastly, requirements. So far so good: analytic mind, strong work ethic, willingness to explore new areas – I’d flatter myself with having most of them, or at least the ability to pretend I do. But then: “This job is only for those completing a Master’s in natural or computer science.” Of course. Right at the end, this handy tidbit of information is easy to miss, delaying the inevitable disappointment. Or maybe it was in the job description, but my bleary eyes didn’t notice.

Internships in Oxford

Not everyone is this inept at finding something to do with their free time. Thousands of students in Oxford each year take up opportunities at a huge range of different firms, bodies, and organisations. Of course, the stereotype of rich kids interning at their parents’ firms still persists. Many students describe feeling pressured to get some kind of work experience, and cite the importance of connections and networks in getting desirable jobs. One person told me that it feels like everyone “knows what they want to do” and that “if you don’t know what you’re doing, you feel like you’re behind everyone”.

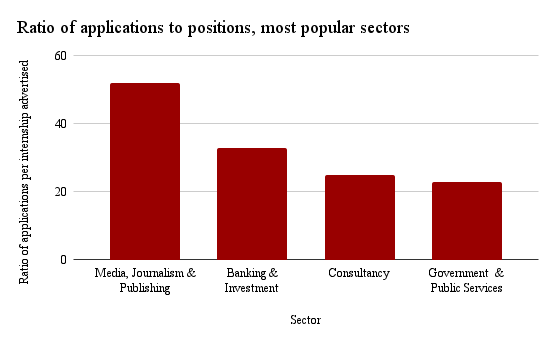

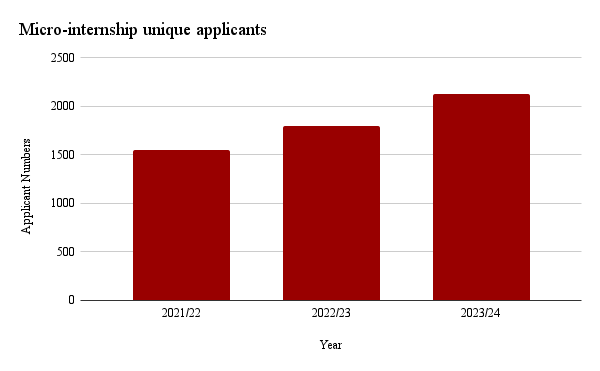

One way in which Oxford students try to break into the jobs market is through the Oxford University Careers Service. They offer both micro- (a week long) and full internships exclusively to Oxford students, as well as running a range of workshops and talks throughout the year. Micro-internships are a popular way of getting experience: you’re “just competing against other Oxford students, so it’s easier to get in”, as one put it. However, for some of the positions advertised, competition can be fierce. In the 2023-24 year, the most competitive sectors for summer internships were Media and Journalism, with over 50 applicants per place, followed by Banking with 33, and Consultancy at 25 (Figure 1).

The large majority of these applicants are undergraduates, with just over 30% of the undergraduate body applying to summer and micro-internships. The highly competitive nature of some of the positions, compared to other sectors with virtually no applicants, suggests that lots of the applications are a segment of the student body fighting over the same few positions.

One potential reason for this is a lack of awareness amongst many students. One second-year student complained that the Careers Service “doesn’t make an effort to interact with students” and suggested that if you don’t know where to look it can be difficult to find opportunities. Another recurring idea is the Catch-22 of experience: lacking enough experience to get positions, which are the very positions that give you the experience you need.

This means that once you get into second year without having done anything in your first, it can feel like the world is against you. Others profit from positive feedback loops, hoovering up a whole array of impressive experiences. This is where claims of nepotism become partially pertinent – those with a foot in the door get ahead and stay ahead. However, opportunities like those provided by the Careers Service offer alternative ways of getting connections and starting these loops.

Pressure to apply

Even amongst the frenetic schedules that most of us have here during term, students still spend a lot of time thinking about and applying for these internships. Applying for a range of different positions, with the multiple rounds of testing and interviews that this entails, is not a minor time commitment. Those who are ruthlessly focused on getting jobs will often spend every spare second trying in some way to get ahead, whether that’s applying, networking, researching companies, or building skills. For others, the applications go on the back burner, allowing time for other things, but often at the expense of peace of mind: at least in applying you have the feeling of productivity. A more relaxed student admitted that: “I should put more time into it than I do.”

Is it Oxford in particular that induces stressful feelings about the need to apply? Despite being one of the best universities in the world (and obviously the best in the country), some students felt ill-prepared to go outside the ivory tower: “we don’t even cook our own food and we barely work in groups”, argued one. Oxford’s reputation as a centre of elites and old boys clubs doesn’t help: virtually everyone I spoke to mentioned worries about internships being doled out to family friends, rather than being judged on merit. One person worried about “the amount of nepotism and networking involved in many private-sector jobs”, and saw work experience as a way to enhance their own connections.

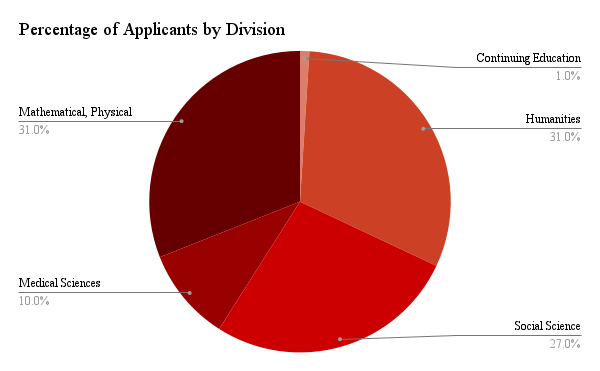

The degree that you’re studying also seems to make a difference. Whilst some subjects, like Law and Engineering, have clear job paths, others suffer from worse reputations. An English student told me that work experience “feels especially important for the humanities and degrees that are generally valued less in the jobs market” and saw their internships as a way to “stand out”. The data on Careers Service summer internships shows that Social Science students are overrepresented in their number of applicants, whilst most other divisions apply proportionately (Figure 3). Many people – myself included – are yet to figure out what they actually want to do with themselves in a few years time. This makes choosing where to apply even harder – but even more pressing, as it’s the best way to explore possibilities.

Time well spent?

According to the Careers Service website, everyone loves their internships. But in reality experiences are more mixed. A few people found micro-internships really enjoyable, working on exciting programs and meeting engaging people. More often, reality failed to live up to expectations. One suffered from “a lack of guidance” and found the workload “a bit overwhelming at times”. Others had almost nothing to do, working only an hour or two a day. Even where this happened, though, many reapplied for mowe the next term, suggesting that the gain in ostensible work experience is more important than actually improving skills or learning.

Whilst formal programs in big corporations are often highly structured and planned, lots of the organisations that hire micro-interns are small and lack the resources or knowledge to keep a student busy for a week. Sometimes, however, it’s the students who make the experiences differ from expectations. One admitted that during their micro-internship she was “travelling quite a lot” and ended up doing the work “on the plane and on the bus up and down mountains”. This ended in an online presentation being done in a noisy cafe where the audience couldn’t hear what she was saying. To complicate things further, due an organising mistake she was advertised as being a DPhil student, despite being a poor second-year.

Another person told me that being an international student can make the work much harder, as a result of incompatible time zones and different expectations. That students are willing to disrupt carefully-planned holidays and important sleep schedules to do their internship speaks to the intensity of pressure to get ahead.

Working preferences

It’s not that students will take absolutely anything, though. The most popular sectors for students applying for summer internships show how dominant skilled service jobs are in the UK economy. Especially for students at elite universities, highly specialised and technical jobs are hoped to offer both intellectual stimulation and graduate premiums. They include tech, development, think tanks, academia, science, consultancy, and marketing. Government & public services and tech are also very over-subscribed. Relatively fewer applicants for law and insurance suggests that companies in these areas have well-established programs which students apply to outside of the Careers Service.

Location also matters, however. The great majority of applications for internships through the Careers Service are for those in the UK, with Europe and North America next most popular, despite many placements also being offered in Asia, as well as Africa, South America and the Middle East. Internship programmes come with a range of different provisions and support, ranging from virtually everything paid for to nothing. The most competitive region is North America, with 24 applications per internship offered, reflecting a relative lack of supply; Asia has the lowest ratio of applications to internships offered, despite boasting the greatest number of places advertised out of all regions.

Structural changes

Oxford is not unique in the kinds of work which its students want to do, and the intensity of job competition. Changes in the destinations of graduates from elite educational institutions show a marked shift towards particular industries and occupations over the last 50 years. This can largely be explained by structural economic changes, including the growing specialisation and digitalisation of economies, the dominance of services in the West, and increased costs of living.

To take an extreme case, consider the US. An article in The Economist highlights that whilst in the 1970s one in 20 Harvard graduates went into finance or consulting jobs, that increased to one in four in the 90s, and now an astounding half of Harvard graduates take jobs in finance, consulting, or technology. Given the prevalence and popularity of finance and consulting societies in Oxford, it seems that we’re not far behind.

One important change is the ‘hollowing out’ of traditionally middle-class jobs: employment in jobs with middle-of-the-road salaries has fallen significantly in the UK, whilst low- and high-paying jobs have both seen significant increases. Graduates from top universities have profited from technological changes which suit their skill sets, giving them access to very well-paid professional jobs. Yet those without degrees or with qualifications from less prestigious institutions have been forced into low-paying service jobs, due to offshoring of traditional sources of decent wages.

Starting salaries in investment banking and other finance jobs easily get into six figures, more than most can hope to get to in a lifetime. Desire for these high wages explains the vast number of people wanting to get into these sectors, and the brutal competition for work in places like Jane Street. And pay in the UK is practically nothing compared to what you can hope to get in the US: big companies on the other side of the Atlantic effortlessly hoover up Oxbridge graduates, with the differences in earnings between US and UK graduates now estimated to be 27%.

Furthermore, the number of adults with degrees has increased by 30 percentage points since the 90s, amplifying trends of job polarisation, where jobs become concentrated in high- and low-paying areas. The decline in sources of employment that don’t require a high degree of specialisation or prior experience, combined with large increases in the proportion of graduates, has made the need to get that internship all the more urgent. The UK has been particularly affected by this expansion: only in London has the number of high-wage jobs kept up with the increase of highly-skilled workers, and the graduate premium (earnings relative to non-graduates) has fallen nationwide. In contrast, in the US the graduate premium has increased even more, as a huge supply of skilled jobs meets the demand. This, combined with other factors, such as astronomical housing prices, means that students face a dizzying set of challenges in living and working after graduation.

Where do we go from here?

Reflections on the future can focus the mind about what you’re doing now and drive the discovery of opportunities that might otherwise be missed. But anxiety and worries about not doing enough can be unproductive and immobilising. As one person I spoke to put it, there’s a lot of “unnecessary fear” and every moment is “not make or break”. Another mentioned the “guilt of missing out”: a perennial FOMO and unflattering comparisons with others. There’s a balance to be struck between future consideration and current enjoyment, but for too many people this balance is impossible to find. This is understandable, of course: changes in student demand reflects deep worries about the future of many industries, especially given developments in Artificial Intelligence and other technologies.

Many young people are starting to think about their futures earlier than ever, sometimes absurdly so. The amount of LinkedIn requests I’ve had from students in their first year of sixth form (or before) who proudly proclaim that they are ‘looking to be insurers’ or already have work experience at all of the Big Four is astounding, and in many ways admirable. Planning ahead is sensible, important – even exciting. And thinking about choosing jobs in which one can stay financially afloat is a privilege that many cannot even access, and for which we should be grateful. But it shouldn’t come at the expense of everything else: friends, family, projects, academic study all matter – and are the things which give you reason to keep going.