Keir Starmer recently announced bold plans for the development of artificial intelligence (AI), investing £14 billion in AI-related projects which will create an estimated 13,000 jobs. Previous commitments to build a supercomputer will be reinstated and a new National Data Library will be established. Starmer and his cabinet are right to invest in STEM, especially in light of the ever-bleak economic picture. We live in an epoch of digital transformation: not investing in generative AI, electric vehicles, and green energy would be foolish. But such substantial investments call into question the relevance, and perhaps the fate, of non-STEM disciplines, namely the humanities.

As a political theory student, I have no doubt that the humanities will always play a vital role in our society. Not only do disciplines within the humanities – such as history, literature and philosophy – provoke curiosity in their students, they also make significant contributions towards the development of digital technologies like AI. Critics are too quick to complain that humanities degrees are frivolous, arguing that they inadequately prepare students for the workforce. Under the Conservatives, previous British governments criticised humanities programmes with low employment rates and non-technical content. These governments pushed the country towards STEM-based apprenticeships. And at a time of financial pressures, struggling universities have followed the money, cutting courses with low student numbers.

Criticisms of frivolity, however, are not entirely fair. Humanities students graduate with the skillset to make a valuable contribution to the world of work. Throughout their degrees they have learned to be curious about the world – enabling them to think critically, be inquisitive, and inspire change. Learning doesn’t always have to be about reciting facts, figures, or calculations. It is also about cultivating the mind.

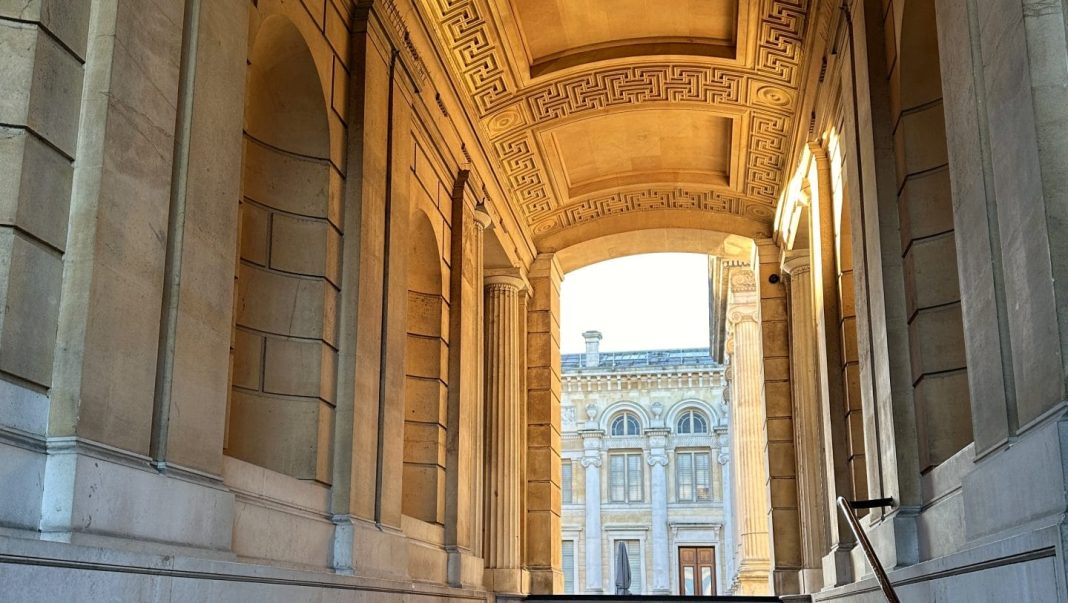

To some this seems frivolous, but in reality, intellectual curiosity has been at the core of education systems for centuries. The communication, team-building, and organisational skills which students develop through cultivating academic curiosity are desirable amongst employers – especially in the media, financial, and legal sectors which humanities students enter en masse. Unlike most universities, Oxford has challenged criticisms of frivolity. The establishment of the Schwarzman Centre, a new multi-million pound home for humanities research and teaching, clearly recognises the value that the humanities have to offer for students and employers alike.

Futility is another common criticism laid at the humanities. Just before Christmas, an unsuspecting PhD student blew up on twitter, now known as X, for her thesis on the politics of smell in contemporary prose. Ally Louks’s work initially garnered support from friends, family and kindly strangers, before it caught the attention of trolls and haters. After that she was inundated with hateful comments, criticising her value-add to society. Underlying these criticisms is the problem of the intangible. The benefits of studying smell in literature are perhaps not as obvious as the headline examples of roads, bridges, and vaccines. But despite its controversy, Louks’ research is concerned with power dynamics, class hierarchies, and gender divisions – questions fundamental to the flourishing of any society.

The analytical and critical thinking skills bestowed upon humanities students are integral to our society. Experts in linguistics have been at the forefront of developing generative AI models which can accurately interpret language, understanding its cultural and contextual background. Meanwhile, philosophers have made contributions to the ethical and policy frameworks which shape the context of technological development. Research centres, such as Oxford’s Institute for Ethics in AI, are a prime example of the contribution which humanities disciplines can make to the forthcoming AI revolution.

It’s true that these contributions can be slow to mirror digital progress. The violence of the UK’s summer riots in 2024, incited primarily by hate speech on social media, clearly demonstrates that ethics and policy experts have some catching up to do. But their slow pace does not undermine the potential of their contributions. If anything it demonstrates the strength of the humanities as a discipline – their long-term, reflective approach to societal problems which grow recklessly from rash technological advancement.

The real problem with the humanities is not the questioning of their value, but that sceptics don’t understand what humanities scholars do. Perhaps this is the fault of academics and students who need to do a better job of engaging with the public. But equally, critics of the humanities shouldn’t be so quick to judge, and government should be wiser with their rhetoric. The fate of the humanities is far from bleak. Subjects like law, anthropology, and geography are the beating heart of any successful society. But if we want the humanities, and ultimately society, to flourish, we must adopt a more human attitude towards this set of profound and socially beneficial disciplines.

Have an opinion on the points raised in this article? Send us a 150-word letter at [email protected] and see your response in our next print or online.