In the depths of the spring vacation, with Finals and the looming emptiness of What Comes After staring at me from the near future, I decided to do some volunteering. The brilliant Turl Street Homeless Action had been a place of emotional refuge for me, so I sought a way to get involved in a similar charity helping the homeless in Milan, my hometown.

I get there at 8.30pm and am immediately recruited to load water bottle cases off a van. ‘There’ is a glamorous covered shopping avenue one street away from Piazza Duomo, Milan’s one architectural wonder and tourist hotspot. Shops closed, the street has been turned into a makeshift food kitchen, with stations where water, snacks, and warm clothes are being handed out to a gaggle of regulars.

The group, who have been meeting once a week for years, is a well-oiled machine. Within minutes we’re packing up, moving supplies to shopping trailers and Ikea bags to bring to those who can’t – or won’t – move from their makeshift shelters scattered around the streets of Italy’s fashion and luxury capital. A gaggle of Boy Scouts, formerly middle-aged women (the sciure, often stay-at-home wives or newly retired professionals, who keep Italy’s non-profit sector running), and retired professional football players, we move between the covered walkways that by day serve as the open-air runways of aspiring models and gallery walls of fashion connoisseurs.

On our way to a bakery, which has kindly donated its leftover pastries to us to supplement the hot drinks and sandwiches, we pass one of the city’s oldest, poshest restaurants. In the glass-enclosed patio, a couple in black tie are picking at a thimble-sized portion of what looks like truffle pasta. I wonder if I should offer the woman, at least 20 years her dining partner’s junior, one of our sandwiches instead. Past the restaurant and the bakery, a village has sprung up.

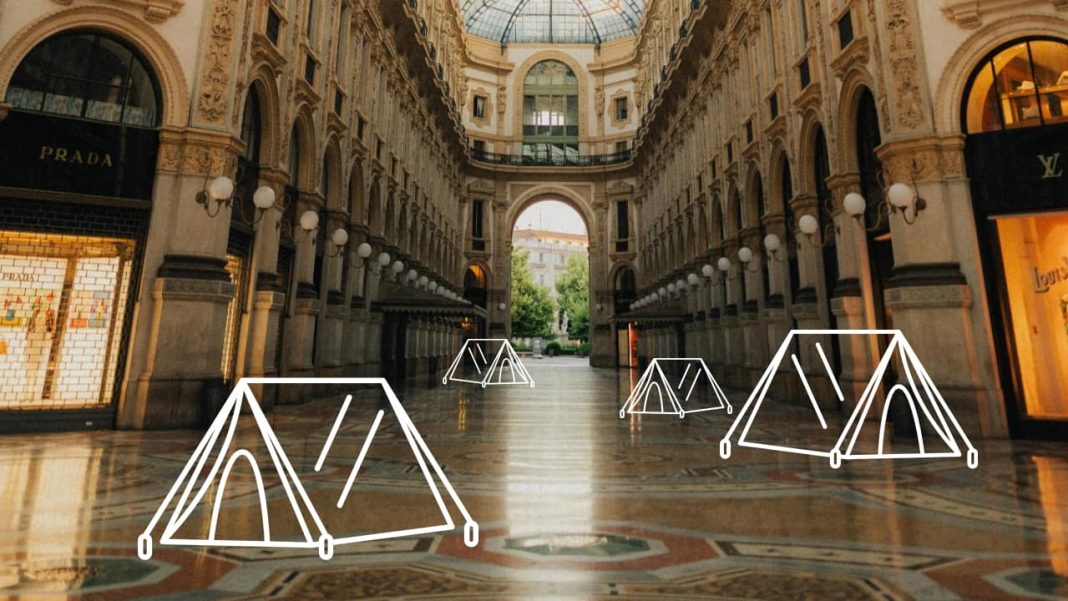

The picture is striking. Milan’s portici, long a symbol of unattainable luxury, of slender bodies and fine fabrics inaccessible to the masses, has been reclaimed and transformed into a scattering of tents, cardboard shacks, and shopping carts holding all the earthly possessions of their owners. As we move between these elaborate makeshift homes and chat to their inhabitants, I recognise a few from the food kitchen I sometimes work at during the day. There’s the handsome, freakishly tall, shamelessly flirty young man, probably a victim of Milan’s ruthless modeling industry (which relies on undocumented immigrants and sub-human wages); the impeccably dressed elderly couple; the group of men charging their phones outside a high-end perfume store. One of them is on a video call with a woman and a small army of young children, speaking in a foreign language.

I want to ask about their stories, and I want to write about them – and photograph them. The brutal contrast – of high fashion and extreme poverty, of precariously built structures in front of boutiques charging a month’s rent for a belt, of mannequins wearing ‘distressed’ fabric staring impassively at tents heavy with wear – would make for a brilliant photo essay. How such an enormous number of people – over 2,600 according to the latest census, nearly 1 in 500 people in Milan – slipped through the social safety net in one of Europe’s wealthiest cities is something that should be investigated. Asking the people themselves seems like the fairest way to do that, and to refute the Italian right-wing’s narrative that the vast majority of the homeless problem is caused by illegal immigrants newly arrived from Africa. Most of the people we meet speak Italian flawlessly, and many of them have gone to school in Milan; one used to be a primary school teacher in the suburbs nearby.

Some people would speak to me, I’m sure. More would if I became a regular at these Monday-evening volunteering outings; some might even let me take their picture in front of their makeshift shelters. But I can’t help but feel that by taking my camera with me – even by asking for an interview – I’m stepping out of the shoes of a community member trying to help and walking into a territory that is much more predatory. Ultimately, I’m a student trying to go into journalism: I need a portfolio, and an investigation into Milan’s homeless population would be a hit with papers while ticking some nifty virtue-signaling boxes in the process.

Volunteering has never seemed to me to be a transactional relationship: helping others is a fundamental part of belonging to a community and living with the understanding that, if I were ever in trouble, others would do the same for me. Doing the same as a journalist feels like fundamentally changing this relationship, placing myself as an outsider profiting off others’ misfortune.

Many of the people I would be photographing are young; photos of them at their lowest moment could haunt them online long after they’ve started a different life. Older people would have decades of life immortalized in a single, unrepresentative snapshot of abject misery, which may be their only online footprint. There seems to be something inherently exploitative or opportunistic in using others’ three-dimensional, complex lives and placing them in a 3:2 aspect ratio and a couple of sentences on why their plight supports my argument on Milan’s homeless problem. In a city built on capitalizing off photos of skeletal bodies and cheap labor, this feels even more pointed.

The National Press Photographers Association’s Code of Ethics helpfully advises journalists to “intrude on private moments of grief only when the public has an overriding and justifiable need to see.” Does a life spent at the fringes of society count as a “private moment of grief, if it is in the nature of homelessness for lives to play out entirely in the public, not private, sphere? Is even just asking for an interview ethical? Is writing this story itself, a meditation on the morality of (student) photojournalism just as predatory as it sounds, an effort to build the aforementioned portfolio?

Turning the corner to finish our round, we pass the restaurant, where the same couple is still staring morosely at the same plate of tagliatelle. A few metres away, a man is lying face down on a single layer of cardboard, his nose squashed against Milan’s cold marble. He is sheltering from the drizzle in the covered walkway of a high-end furniture store, where the cheapest chaise longue is on sale at €1699.99. As we move to offer him a bottle of water, all I can think is, this would make a great cover page.