Emerald Fennell’s Wuthering Heights, Netflix’s Pride and Prejudice, Greta Gerwig’s Narnia, HBO’s Harry Potter. All these adaptations of well-loved literary classics are currently in production, and, along with other fans of the novels, I have eagerly awaited each new detail of plot changes and casting choices. Yet the original novels of Emily Brontë, Jane Austen, C.S Lewis, and J.K. Rowling have already gone through multiple adaptation cycles, from screen to stage to fiction. Why do these works spawn so many descendants, and haven’t we maybe seen enough of them already?

We can easily – if perhaps cynically – feel that these adaptations are symptomatic of late-stage capitalism. Harry Potter, for instance, is ultimately a product with seemingly limitless earning potential for companies such as Warner Brothers. Or do these cycles of adaptation reveal a dearth in creativity: is it simply easier to sell audiences on something they already know? In an age of doom-scrolling, rapidly declining attention spans, and AI-assisted search engines, are these seemingly endless cycles of adaptations, paid for and provided by media giants, the only literary consumption contemporary readers can engage in?

Well, perhaps. But these adaptations also stem from a cultural precedent that can be traced back to the writers of the classical world.

The ancient Greek poet Bacchylides wrote: “one learns his skill from another, both long ago and now.” Imitatio in the ancient world was a rhetorical practice where work which most closely resembled previous masters of the genre was a sign of the author’s literary skill and cultural value. In this world, imitation was not only the sincerest form of flattery but the highest form of art.

It was partly through imitatio that Chaucer established English as part of the great literary tradition. Chaucer’s long poems ‘The Book of the Duchess’ and ‘The Parliament of Fowls’ make use of passages from Cicero and Ovid, reworking the same material and yet creating something new. These poems involve the “long ago” of the classical world as much as they do the English literature Chaucer was helping to create. The “now” of Bacchylides is then in some ways applicable to our current literary moment, with producers such as Gerwig and Fennell reworking the rich ground left by earlier authors.

But what is it that makes these books so adaptable, so readily reworked, and offered up to each new generation? Again, the answer seems to contradict underlying cultural assumptions of what makes works of literature valuable.

All four works are genre fiction: Wuthering Heights is a gothic novel, Pride and Prejudice a romantic comedy, Harry Potter and The Chronicles of Narnia fantasy. The primary audience of Austen and Brontë are women; of Rowling and Lewis, children. While our image of cultural taste-makers might be, predictably, a group of old white men with so-called ‘serious’ fiction, it is the literary favourites of women and children that have proved to be most enduring.

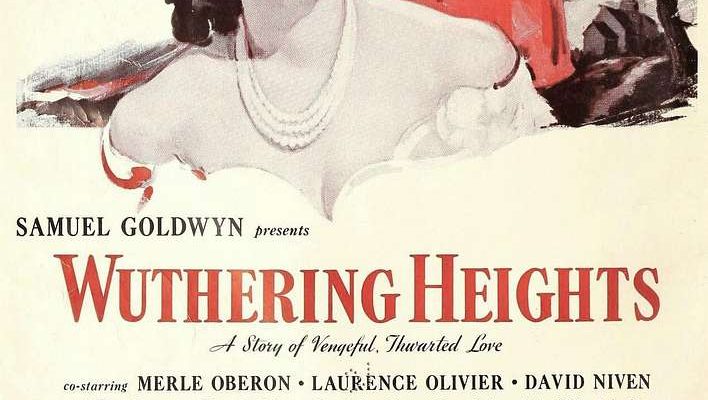

Yet as much as literary adaptations shake prescribed cultural values, they can also do their part to enforce them. Several rumours surrounding Fennell’s Wuthering Heights have caused outrage amongst fans of the book, ranging from a rather sexually explicit opening scene to an anachronistic wedding dress more suited to the 1980s than the 1810s. More insidious is her decision to cast Jacob Elordi, star of Fennell’s Saltburn, in the role of Heathcliff. Brontë’s Heathcliff is more than a needlessly broody Byronic figure. Adopted amongst the trading ports of Liverpool, a character in the novel wonders where Heathcliff “[came] from, the little dark thing?”. The Heathcliff that appears in Brontë’s Wuthering Heights is heavily suggested to be non-white. Elordi’s Heathcliff, not so much.

Wuthering Heights has always been the subject of controversy: contemporary papers even called the novel “semi-savage”. Yet it is sadly ironic that it seems Fennell’s adaptation has side-lined one of the most truly confronting things in the novel. While I will join many others in the cinema this Valentine’s Day to watch Fennel’s adaptation, I will also reread the original, appreciating Brontë’s text as the soil upon which each adaptation has grown. While modern adaptations allow us to rediscover well-loved classics with new eyes, not every decision they make is an improvement on the original.