In a windowless room in an abstract part of Oriel, I sat in on a rehearsal for Annie Baker’s The Antipodes (2018), on at the Pilch this term. There was a large table with five of the cast huddled around, strewn with miscellaneous snack debris – crisp packets, an apple, a large popcorn multipack – as director Kilian King shouted instructions to “keep making more empty packets”.

This debris is crucial to showing the passage of time, as Baker’s play spans a long, exhausting series of meetings where the characters attempt to come up with a good story for a somewhat unclear cause. Struggling to come up with ideas they all approve of, they tell different tales to each other in order to try and find some inspiration, all the while the stress and mania of being trapped in the discussion room mounts and fear and panic over their jobs, sanity, and the opinion of their imposing, venerated boss begins to set in. The characters all seem to be perpetually working, even sleeping in the office, so the first glimpses of the play I saw were the swift clearing of the table for morning scenes and the rescattering of the mess to indicate the passage of time to the evening, over and over, letting the days run into each other and time become immaterial. It was snappy, and detailed, and had a really brilliant effect (especially after the first couple of run-throughs) showing the careful attention being paid to the show’s specifics.

Setting the actors free to go on break (and film the mandatory marketing material), I got to talk vision with the directing team. Kilian told me that since the script itself was very precise, both in the sense of its stage directions and in its dialogue, a similar level of attention was needed in the staging and directing of the show. One of the assistant directors, Anna Stibbe, said she felt especially interested in the details, like small environmental objects or minor expressions, when thinking about how she wanted to stage the show. Kilian’s directorial vision was about “putting it on in the way that makes sense”, which to him, since the play isn’t especially famous or canonical, meant working with the text rather than attempting any great subversion. Certainly it’s been rather fashionable lately in Oxford to (sometimes drastically) reinterpret the work you’re staging – recall cameras at the Playhouse, Doran’s rather uninspired pseudo-feminist ending to Two Gentlemen of Verona, strobe lights and free shots in Julie, or Anna Karenina with pantomime comedy – sometimes done successfully, and sometimes risking coming over a bit ‘fur coat, no knickers’. Additionally, there has been comparatively little engagement with contemporary work (perhaps because the rights are cheaper for out of copyright shows with a special twist), making Kilian’s approach to The Antipodes feel genuinely refreshing.

Having seen part of the show, I still think his summary of his directorial vision is quite a reductive description of the subtle and very deliberate direction of the cast – objectively, yes, the decisions make sense, but they also draw out the implications, humour, and depth of emotion of Baker’s prose. There is no random, left-field reimagining going on, but certainly an incredible amount was brought to the script both by its direction and the participation of the actors in character decisions and performance.

Kilian also talked to me about the vision for the set, managed by set designer Leon Moorhouse with assistant Elle Jardine, describing the construction of a sort of room-within-a-room. Around the central board table, the ‘boardroom’ itself would also be constructed on the stage out of UV paracord in a box structure, to heighten the claustrophobic sense of the show. The most successful Pilch shows have always been the ones which engage with the space beyond just accepting its black walls, such as the impressive draped-fabric room effect of The Goat or the changing seat structures of Tis Pity She’s a Whore, and I’m excited to see how this voyeuristic set design will interact with the play’s concern of storytelling, watching, and being watched.

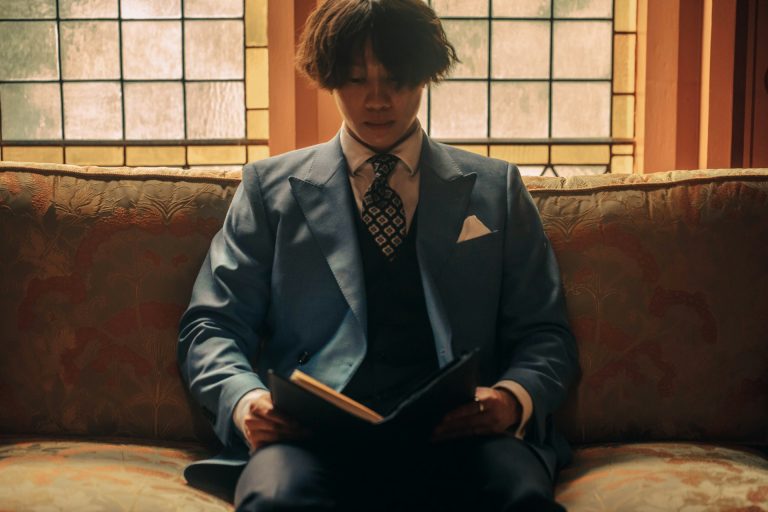

I asked Kilian a little about character, and he summoned over Cameron Maiklem, who plays the often-offstage yet ever-present Sandy, the group’s revered boss, seemingly at first to do a pretty good Trump impression. Cameron talked to me about Sandy, whom he described as a respected and successful but ‘fatigued’ man, which Kilian noted was something he hadn’t considered about Sandy himself until Cameron brought it to the performance. In my conversation with Cameron and across the rehearsal, the extent to which the actors were being encouraged to consider the interiority of their characters really came across. Though in theatre, every event from curtains up to curtains down has been considered, planned, and doesn’t change, the cast seemed to have an approach of genuinely working through why they would behave in a certain way, why they’d say something, or why they’d react, with a great emphasis on the interiority of their characters throughout and creating a naturalistic feel to the performances, which is necessary to ground such a disorienting narrative. As Kilian declared to the room: “You have to like your character! Find what you like about them!”; it felt that each had a strong identification with who they were becoming when the scenes began. This identification is especially well utilised in a show like The Antipodes, as much of the emotional tension rests on the slow divulging of increasingly personal stories and reactions to the rest of the room.

Something else notable about the rehearsal was actually the atmosphere – despite the often heavy content, the cast seemed more like a group of friends during the breaks, passionately debating about mermen and planning their own cast socials. While this is always a better environment for rehearsing, it also created a strong chemistry quite necessary for a production so dependent on the collaboration of the ensemble. Due to the story swapping and the shared hysteria in the show both relying on its ensemble nature, this collaboration is especially necessary in The Antipodes, and to me seemed especially well executed. I watched a scene towards the end of the show (so I’ll try not to spoil anything!) where, exasperated and tired, one of the writers, played by Sanaa Pasha, begins to spin a strange, monstrous Genesis-like narrative, gradually waking up the rest of the room and drawing them in as the story moves from bizarre to gruesome to gentle to tragic. Though it was an earlier run-through – Kilian preferred to run it and see how the cast respond to it themselves rather than being too prescriptive – it was clear the off-stage relationships had the cast responding much more naturally to each other on stage. The rising intensity of the story being told was stopped suddenly by characters bickering; the tension burst, and I realised I was sitting forward in my seat.

The Antipodes, when I saw it, was still over a week from being staged, but already showed the promise of an unmissable night at the theatre. Amongst some trend of exaggeratedly shocking or obscene student theatre seemingly for its own sake, this production engages with the naturally unsettling tone of Baker’s sharp prose and its inherent strangeness. It is clearly being directed by a precise vision of the nightmarish tone of the show’s prose to create an almost magical-realist experience, and is brought to life by a cast with strong identities for their characters and stronger ensemble chemistry. The Pilch is known for its more experimental and unusual offerings, and I think The Antipodes is the termcard listing I’m looking forward to the most – well-made, new, and genuinely, properly, actually weird.

The Antipodes is on at the Michael Pilch Theatre, June 4-7th.