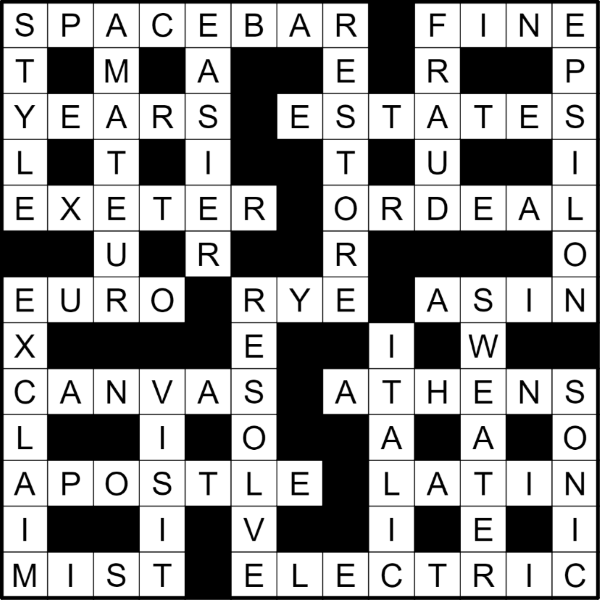

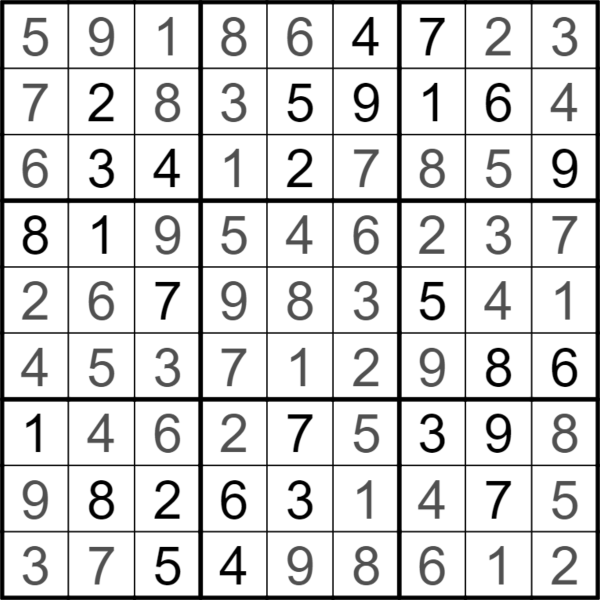

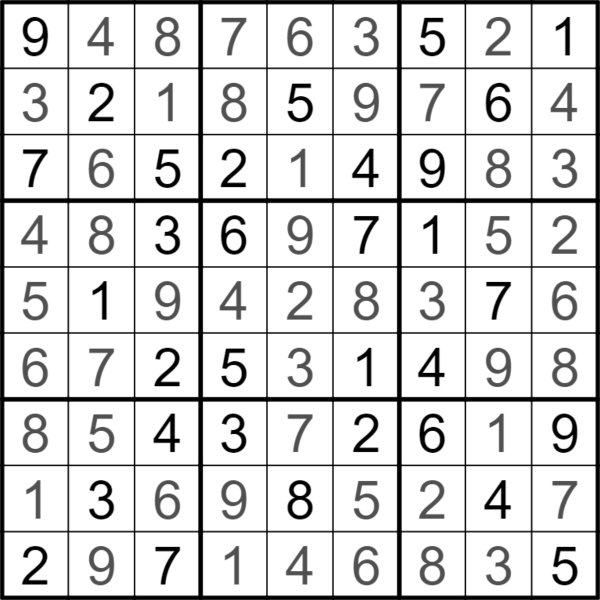

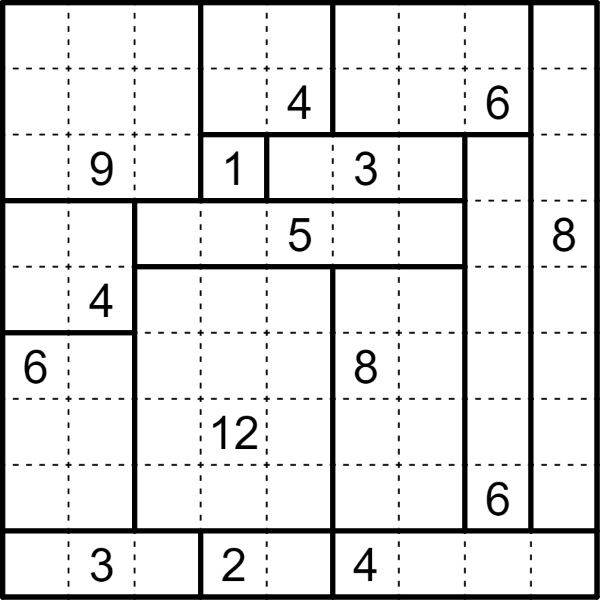

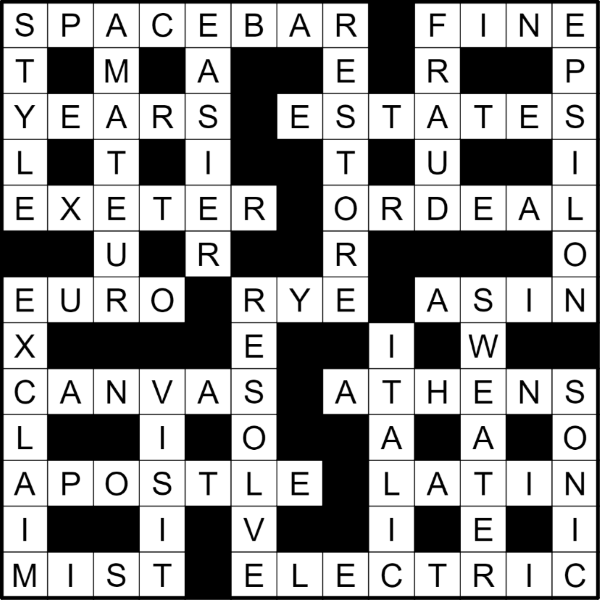

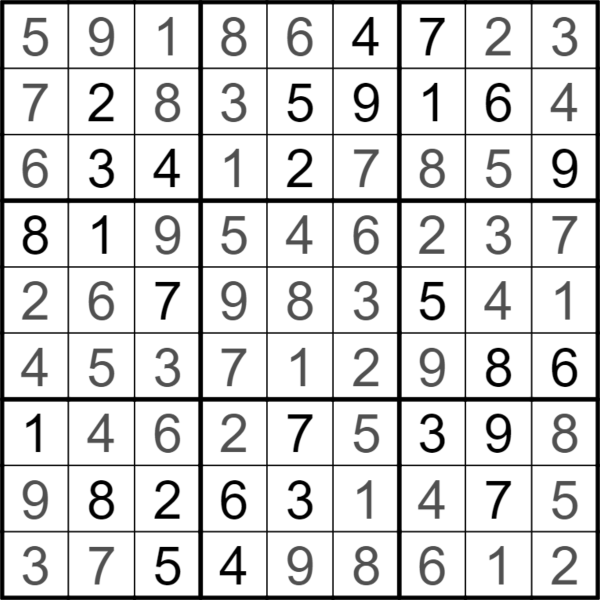

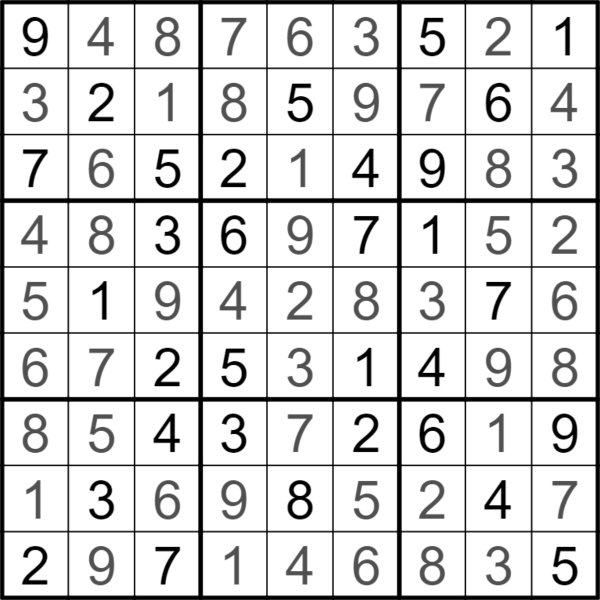

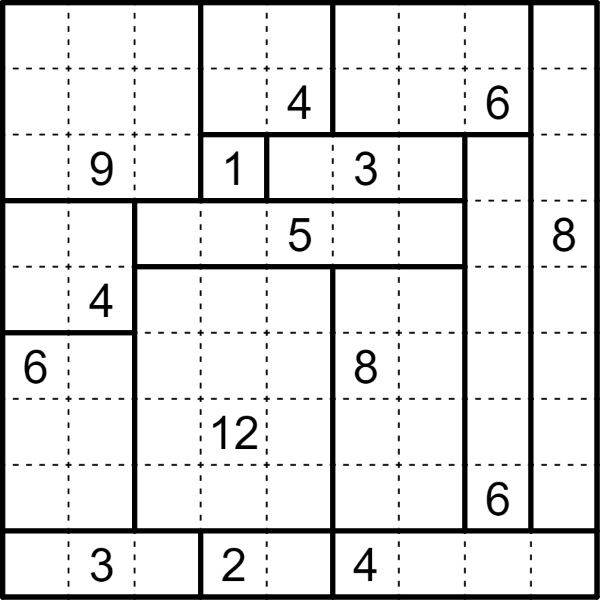

Solutions for the last batch of puzzles in Hilary term 2023. The puzzle team would like to apologise for 5 down, where the answer was used as the definition.

Solutions for the last batch of puzzles in Hilary term 2023. The puzzle team would like to apologise for 5 down, where the answer was used as the definition.

Gusto, the new Italian restaurant on Oxford High Street, is fascinating in so many ways. There is a huge focus on the quality of ingredients and cooking with some brilliantly crafted dishes on offer. All of this is inside the vast old Mitre pub and the scale of the site means that there is room for a cafe and bar area, a huge upstairs private dining room, and countless different dining spaces with their own unique styles. You can come here for a coffee and cannoli, brunch, a Sunday roast, or all of the Italian classics you know and love.

I have been lucky enough to visit a few of times over the last month or so, sampling a wide variety of the dishes on offer. The first trip was a lovely evening service in one of the dining rooms away from the kitchen floor. Here, we sampled the whole sea bream sharer. It comes in at £50 and is served on the bone (just how I like it) on a bed of potatoes, red onion, white chicory and samphire. In terms of a showstopper first experience, this really was superb and the theme of fish and seafood starring continued throughout my future visits. The bream itself is perfectly cooked and filleting it yourself tableside is thoroughly enjoyable!

The pan-fried sea bass was also a more than pleasant surprise. It is paired with some winter greens that match perfectly and a balsamic dressing that suggests a really well-thought-through dish — a cheese potato gratin also accompanies. The fish itself was perfectly cooked with a delightfully crispy skin. There is also salmon on offer and this one is a whole event in itself. The dish is brought tableside in a dome and the steam is released. The roast potatoes with it were a little disappointing and the salmon a touch overdone but again it was the sides that shone. There are green beans and butter beans with a salsa verde that combine superbly with the fish.

The variety of starters is predictably eclectic but I would certainly opt for the slow-cooked meatballs. They arrive in their cooking pan with a punchy tomato sauce and a focaccia crouton. A dash of Gran Moravia cheese comes on top but the star is definitely the tomato here. You can really tell that it is cooked slowly in house and it leaves you asking for more bread to go back dippining with. The balls themselves are succulent and flavourful with a vegan alternative surprisingly similar. Calamari are also on offer and the squid itself is clearly of high quality. As is so often the problem though the batter tended to dominate.

And then onto the pizzas! These really are the star of the show and the impressive pizza oven in the open kitchen dominates the main dining room. You can also book in for a full ‘Pizza Experience’ which involves making your own with the help of the star pizza chef (and eating them afterwards of course!). Quite amazingly, the sourdough starter that was created in the first Gusto restaurant is used across all the sites, guaranteeing consistency. That sourdough really does make a difference too and makes these stand out from many other conventional pizza bases. We tried both the Truffle Bianco and the Carnivoro. The first is a white base with mushrooms, mozzarella, rocket, and Gran Moravia cheese. The truffle paste adds an interesting twist but you can tell that it’s not genuine shavings — the benefit of the paste is that it bakes in with the cheeses and mushrooms to ensure it flavours every aspect of the dish. The Carnivoro is a meat-lovers dream with ragu, nduja, slow-cooked pork, pepperoni salsiccia, prosciutto ham, Fior Di Latte mozzarella, and caramelised onions. There is so much going on here to such an extent that getting a complete bite is almost impossible but when you do it is worth it! The ragu is certainly the most flavourful of all the sausages but is balanced out well by the onions, parma ham, and mozzarella.

In terms of sides we tried the Caesar salad, the house salad, and the fried courgettes. The Caesar salad was perhaps slightly overdressed but I was so happy to see it come with the anchovies that are often ignored that it mattered not. The house salad is my favourite though and brings a much-needed freshness to any of the spicier mains.

Now, ‘Dough Petals’ are quite the thing here at Gusto. You can get them as a savoury starter three ways; with garlic, with tomato and shallots, or with pork, fennel, mozzarella, and onions. We kept it simple with the garlic and weren’t disappointed – if you are a garlic lover then this is a must-have. The real brilliance of the ‘Dough Petals’ though is when they are used for dessert (bear with me I was highly sceptical too). The Biscoff and chocolate dough petal sharer is an extraordinary creation. An entire pizza base is filled with Biscoff and dark chocolate before being rolled, sliced and folded. It is then baked in the pizza oven and served on a base of berries and topped with vanilla ice cream. This might seem like overindulgence and a serious sugar overload but the vanilla, mint, and berries somehow manage to balance the sweetness to create my favourite thing on offer here. This can easily be shared by more than two and is the dream finish to an evening meal. There is a Tiramisu too and don’t get me wrong it was good but if you are staying for dessert then this really is the only option (I have been back for it three times already).

Drinks here are also an experience in themselves and the bar and cafe areas make this a great option for a pre-dinner drink. The smoky old-fashioned goes above and beyond with the presentation and the espresso martini comes with chocolate truffles for a complete dessert course. The cannoli on offer here too are freshly piped with a superbly flaky biscuit to differentiate themselves from their store-bought counterparts. What is more, you can enjoy one with a coffee for £5 during the day if you are looking for a work spot.

The last thing to reflect on at Gusto is the space itself and it really is extraordinary. The main dining room has an open kitchen and a great buzzing atmosphere all night. If you are looking for something more intimate then that is definitely on offer in the two rooms alongside it that each have their own aesthetic. Upstairs is a private dining room complete with its own kitchen and bar that is available for hire with a minimum spend but no extra fee. Downstairs is a maze of cellars and caverns that have potential for conversion and so much going forward. They had the chance to create something completely from scratch here and in a tiny space of time, the Gusto team here really have done the old Mitre justice.

It was also great to chat at length with Sales Manager Undine and Head Chef Mukrram. That podcast is below and definitely worth a listen — we go in-depth into the business and the food passions of both of them. The youth and genuine love for cooking are so evident in Mukkram and such a delight to see.

So, to sum it up, Gusto does it all. If you really want you can come here for a burger and chips but quite frankly you wouldn’t be doing it justice. Get a drink at the bar first and then head through to the main dining room to watch on as an authentic Italian dish is crafted in front of your eyes (and don’t forget those dough petals!).

By the end of 2021, having accumulated a book count higher than the IQ of the typical Matt Hancock enthusiast, I decided that I was going to start disseminating Haruki Murakami propaganda – starting with my boyfriend Zach. After reading fifteen of his books that year, I was certain that I would become Oxford’s resident Murakami expert and that my boyfriend would know all about it.

The work in question is Norwegian Wood, a nostalgic Japanese novel undoubtedly popularised by the world of BookTok. But I’ve decided that I have bragging rights in claiming that I discovered Murakami long before notorious BookTokker, Jack Edwards, did. It follows the coming of age of Toru Watanabe as he tackles loss, sexuality, and turning twenty, marking the first year of adulthood in Japan.

I was introduced to Norwegian Wood by an old school friend when I was fifteen years old, and we would, of course, giggle stupidly on the bus over any hint of sex. It is safe to say that although I thoroughly enjoyed it, at the time I could not do the novel enough justice, so when I wanted my boyfriend to dip his toes into Murakami’s mastery, I got him his own copy. I take my book-giving very seriously!

Since he was a professional twenty-year-old, I was curious to see what Zach would say, whether he’d like it or resonate with it at all. Is the experience of turning twenty universal? Or is Murakami just weird? Probably. But I wanted him to read it because it was this novel that sparked my interest in the author, and I hoped that Zach could help me answer questions about adulthood that, for me, were blocked by naïvety. Yet, it seemed that above all, the theme of loss that swamps the novel was the most poignant for him.

Zach was struck by the stoicism of Murakami’s writing; Toru loses countless people in his life through suicide yet adopts an almost apathetic stance towards their deaths, as though we simply ‘move on’ from it. Being Japanese myself I had never realised how unhealthy Japan’s view of death is, and whilst Zach may have found the novel to be helplessly awash with it, I was plagued with the normalisation of poor mental health in Japan. The translation may have played a part in shaping this perspective, however. Zach wishes he could have read the novel in its original Japanese. Whilst I had the privilege of being able to do so, I found the faith we place in translators fascinating.

Upon asking my boyfriend what he found most interesting about the novel, surprisingly he mentioned the suicide of Toru’s childhood best friend Kizuki, who dies prior to the beginning of the novel. Zach resonated with the idea of losing touch with friends: Kizuki leaves this world with an outdated perspective of life, unbeknownst to the person that Toru becomes all these years later. He has been left behind, blissfully unaware of the fact that time keeps going, the world keeps moving, and people keep living. This representation of the past is what stuck with Zach the most. People you lose touch with retain an obsolete image of you, and there is something quite freeing that you can no longer do anything about it.

And as I approach twenty myself, I find myself yearning to pick up Norwegian Wood again, to appreciate it not by reducing it to a naughty romance, but to read it as a vignette of the past. As for Zach, he knows that Norwegian Wood is only the beginning and that soon enough he’ll be just as enamoured with Haruki Murakami as I am. If it were up to me, I would make every day International Book Giving Day.

My Uni room certainly provides a window into my soul. The ground floor room resembles a goldfish tank from the outside. Neighbours can peer through a very thin, pointless mesh, cover to see me chained to my desk or pottering around with my seventh cuppa of the day. The exposed room, overlooking the smoking area, makes the perfect people-watching spot. I can see the smokers with damp hair on a Saturday morning, the MCR’s extravagant welfare teas on the picnic bench surrounded by cheese and a surplus supply of biscuits. If I’m in my room getting a much-needed early night before another bender, I can listen to people confess their deepest darkest secrets after a few vodka shots before Bridge Thursday. Real-life audio books send me off to sleep as I listen to another disastrous love story. Friends can tap on my window and chat there rather than send a text or MCR students occasionally peer in curiously and even wave if they’re feeling brave. Late at night, unexpected tapping on the steamed-up window can come as a jarring surprise, but it is nice to be in such a social spot.

After moving into my tiny first-year room, I was in awe at the beautiful view of Exeter library. The comings and goings of the 24-hour library was unmatched. Freshers flocked to Westgate to shop for their new rooms, determined to make them their own. Pinboards were plastered with photos from the infamous Free Prints app and clothes horses made those relying on circuit laundry, unreliable dryers, and radiators, green with envy. In Primark, I found the items that make my uni room feel homely, and I discovered how much I liked the colour pink. I love my floral bedding and two cushions that – when put side by side on the single bed – can deceive even the cleverest of Oxford students that it’s a double. My blue touch lamp has always entranced students for its ability to light up with an accidental brush of the hand at Pres.

Uni rooms show the unique quirks of a person. Some people have shelves full of plants, beautiful books, miscellaneous ornaments, or bananas and protein powder. Fairy lights can light up even the darkest nights, instantly elevating the room. Small lamps are the best way to make the room homely. The light on my ceiling looks like it could belong to a hospital, whilst the lamps offer the perfect glow for cosy nights.

When I returned to our flat for Hilary term, I opened the door and jumped out of my skin to discover a life-sized cardboard man. I moved him to our kitchen, but he surprised me every time I opened the door.

I’ve grown to love both the rooms I’ve had at uni because so many magical and mundane memories are made there. It is possible to make a once prison-like room feel like a home, with just a handful of pictures, a few fairy lights, and a cushion.

It’s a sunny Monday morning. You’ve woken up early enough to shower, get dressed, and head to the RadCam to tackle the mountain of reading ahead of you. You couldn’t possibly settle for a shadowy spot on the ground floor, so you haul your heaving Longchamps bag up the spiral staircase to find a window seat so that you are visible to all who scan in through the plexiglass gate. Or maybe you’ve returned after lunch only to see that everyone else had the same idea so you make a few awkward circles around the balcony level before settling for a seat with good visibility, and you’re willing to forgo the plug socket to make it happen.

Either way, your heels click as they tap, tap, tap on the wooden floors, and you can be certain that your presence has broken the concentration of at least a few people who peep their heads up to check who has broken their flow. You finally sit down and open your battered copy of Middlemarch or The Cambridge History of English Romantic Literature. You are the epitome of a light-academia, main-character aesthetic. But is there any point putting this much effort into your appearance? Does dressing the ‘part’ make you any more motivated?

Since arriving in Oxford I’ve spent more time than is healthy pondering these questions, observing (from a less coveted seat) the hierarchy that exists between those who could easily be moonlighting as models and the average student who simply turns up to work. A friend who recently graduated warned me of the ‘intimidating’ clique of women who will always turn up to lectures at the English faculty immaculately dressed. I think the same can be said for most Oxford libraries. As I write this, I am sitting in the Lower Bodleian on a very busy Tuesday afternoon. There is a range of people surrounding me, and I will endeavour to describe the most distinctive and trendy that are on display here at Oxford.

There’s always the sea of faded tote bags and leather blazers. Or fishnet stockings if you’re really committed to the look. This fashionable-grunge vibe exudes ‘messy and spontaneous but still sharp and stylish’ in the form of barrette clips and a skinny scarf. This outfit makes dressing down an acceptable norm, and has been a reigning trend throughout 2022 and 2023.

Perhaps on par with this edgy and spontaneous style is the ‘light academia’ OOTD. This one is commonly observed in the English faculty. Some trademarks are the long beige trenchcoat and a black ribbon in hair. A similar tote bag from a museum, but perhaps not so faded. This person definitely takes handwritten lecture notes with a fountain pen whilst dreaming about their solo trip to Paris over the Easter vac.

Now, I’m told that college puffers did not become a mandatory wardrobe addition until as recently as five years ago. Nevertheless, there tends to always be that group who congregate in the college library, repping their college puffer and a stash hoodie – even the college joggers for good measure. They probably all hold JCR office positions. These people are very down to earth, and very dedicated to churning out all those essays or problem sheets. You’d want to befriend one of these people if you plan to beg shamelessly for reading notes.

Oxford is a place where eccentricities are accepted; appreciated even. Many of us were ridiculed in school for being academically high-achieving, and the quintessential English ‘country clothing’ aesthetic signals the most serious kind of academic. It’s unlikely that these people are taking time out to read the Cherwell, unless it’s a political scandal concerning the racist claims made by an elderly tutor. They often opt for something that camouflages them – whether it be olive or green gingham, and they prefer a classic briefcase as their hold-all. Still, they’re not afraid of accessorising, and may be spotted in a bow tie and flat cap. Typically seen in Duke Humphrey’s or Upper Bod. Sometimes in the RadCam, although I’ve spotted a handful within my college library alone.

For some, feeling good in what you wear does wonders for productivity and motivation. Libraries are the microcosm of our academic life, the hub in which students congregate from all corners of Oxford. It’s natural to feel on display, and expressing your trademark style or individuality is a way of showing who you are within an academic setting. Whether it’s to confront an essay crisis or to catch up on tutorial reading, we have access to some of the most beautiful libraries in the world, and it may not seem fitting to turn up having just rolled out of bed. If we are committing to three (or four!) years of an intense degree, we might as well do it in style.

On 25th February 2022, I was detained under Section 2 of the Mental Health Act 1983. I had entered a psychotic episode which had begun (in earnest) on 19th February. The Oxfordshire Crisis Team had been involved in my care since 21st February, before they deemed me in need of hospitalisation. A year later, I feel comfortable enough with my experience to share it with the world for two reasons. Firstly, in the hope that this article will reach someone who needs it. Secondly, to raise awareness of psychosis and what lesser-discussed mental illnesses can look like.

Anniversaries are odd things. Birthdays, the death of a loved one, breakups, marriages; all celebrated or commiserated, after one orbital period around the sun. They force us to reflect. This particular anniversary is the most unsettling and bizarre reminder of the passage of time that I have experienced in my life to date. I never expected to be sectioned. Subsequently, I never expected to be able to return to Oxford. Somehow, in the space of a year, both of these things happened.

A lot of people are unaware of what psychosis is. Essentially, it is a disconnect from reality which takes the form of delusions or hallucinations: seeing, hearing, feeling things that are not there. These are known as the positive symptoms of psychosis. Many things can trigger psychosis: stress, depression, and marijuana, among other factors. In my case, it was likely a combination of all the three mentioned. Psychosis has negative symptoms too, and often these can be more debilitating in the long-run. People appear to withdraw from the world around them, they take no interest in everyday social interactions, and often appear emotionless and flat.

The positive symptoms of my psychosis took the form of delusions. In their most coherent form, I believed there to be a conspiracy against me by the state. I believed that my room was bugged, that there were hidden cameras everywhere, and that the radio and TV were speaking to me and me alone. A laughable thought now, but a terrifying reality to live in. I believed my friends to be spies. I thought this made sense, I’d always wondered why they were all so good looking.

I remember most of my time in the hospital. It was not a good experience; I had no toiletries or change of clothes for over a week. I was in isolation for 10 days as a result of the legacy of Covid. This made my delusions even worse. About a week into my stay I was diagnosed with psychosis and prescribed aripiprazole; an antipsychotic. This made me very restless, I remember pacing around my room relentlessly. However, the medication settled and I began to return to reality.

The delusions were terrible, but returning to reality was the most difficult part of psychosis. I had done and said some terrible things to those closest to me, accusing them of spying on or harassing me. I had hurt my family, ignoring them for days on end and then berating them for their stupidity. I made a fool of myself in front of several of my tutors, declaring my unrequited love for one and sending bizarre emails containing codewords to others. The forgiveness and understanding of my illness that I have been shown is something I will never be able to repay.

The negative symptoms of my psychosis began to emerge as I returned to reality. This manifested itself in the longest depressive episode I have experienced, lasting from March to October. I was sleeping twelve or more hours a day, not leaving bed, contemplating suicide and playing an unholy amount of board games online. I had suspended my studies for a year, so I suddenly faced an overwhelming amount of time to fill, all while wanting none of it. I wanted to be back at Oxford, like it was before I was ill (I am still nostalgic for that era, but I can now accept that it’s a chapter of my life that has closed).

In the autumn I began to accept that I had to find a new way to live and tried to move on with my life. I got a job, spent more time with my parents, adjusted my medication, started revising for finals and attended Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). All of these things helped. I spent those final months at home working on myself rather than hating myself. This was a much harder task.

Emerging out of a depressive episode is like the first spring’s sunshine. Glorious, full of hope. However, there is no trick to recovery, no magic bullet. It is a difficult and long process that requires commitment, patience, and perseverance. It takes a toll on one’s physical, emotional, and mental well-being, and often requires making lifestyle changes, seeking professional help, and developing a support system. But the great thing? It is possible. I know because it happened to me. I feel the rays of this February sun on my skin and I embrace them like a long-lost friend.

In January I resumed my studies at the University of Oxford, Wadham College. This is the proudest achievement of my life. The days have their predictable ups and downs but overall I am happy, healthy, and independent. I am grateful for each adjective respectively.

In summary, I hope this article has been informative for those of you unaware of psychosis. I also hope that it has managed to reach someone who is earlier in their recovery than I. If neither, I can at least say that it was cathartic to write.

This February, this anniversary, three-hundred and sixty-five days after my sectioning, I can say with confidence that recovery is real. I have laughed until my stomach hurts again, sung in the shower, savoured my coffee, and loved the world so hard it takes my breath away. Here is to another year of recovery, of life, for you, and for me.

Addendum: I would not still be here to recount this story without my family, Hannah, Mike and Zack. There are too many others to thank for my recovery. Of note include Katie Overs, Jo Preston, my nana, my grandma, Jenny the dog, Anthony and Carolyn, Steph Potts, Charlie Grayson, Kiri Ley, Keir May and Leo Nasskau.

Children of divorced parents with shared custody develop an attitude to their physical surroundings that is rooted in acute awareness – a heightened perception to how their space makes them feel. Carting back and forth every two (or three) weeks between houses, hauling cardboard boxes, stuffed animals, books, favourite blankets, children of divorce lose faith in the notion of home. Solid ground and cemented bricks may be physical manifestations of home, but they hardly provide stability. The only constant that remains for these kids are their identities, what they choose to bring with them and, indeed, what they leave behind.

Eventually children of divorce grow up, but their habits remain clear indicators of their respective upbringings. Two childhood bedrooms as a shrine to self-fragmentation. As a child of divorce, I’ve observed that there are different approaches that those from divorced families take towards interior design and the decoration of the physical spaces that characterise us. There’s:

The Minimalist:

The minimalist will do anything to prevent feeling overstimulated, crowded, busy, or flooded with emotion.

I would put myself in this category. Growing up, I found that there was always too much and never enough space. Children of divorce learn from an early age not to get attached to places that they can’t guarantee will be there for very long. Instead, they carry a sense of home on their person like a keychain. follows them around wherever they go. But that’s just not sustainable, it’s too much stuff. But resolving the issue by purging their belongings doesn’t really solve the problem. We Depop and Vinted and Charity Shop away anything we can’t realistically see ourselves wearing or using. But what is realistic? We feel lighter by reducing the stacks of clothes and piles of trinkets that cover our rooms, but at the same time reduce the space we take up.

But we are minimalists, not robots. It’s all about the sleek, clean, palatable aesthetic. We disinfect obsessively and change our sheets more often than we’d like to admit because that crisp laundry smell is the same wherever we travel. We clean toothpaste specks off of our mirror with soapy water and a microfibre cloth. On the off chance that we indulge in a stack of books (because our shelves are too full), each one has to be parallel to the one beneath.

We pack light. We micromanage. We prioritise efficiency, good time management, and strict routine. We’re the parent of the group. Either that or the diva of the group, insisting on completing our 25 step skincare routine before going out anywhere. It’s an exhausting life but we don’t know how else to function. We develop a lifetime of quirky (read: neurotic) habits that we don’t mind being bullied over because the alternative is, well, mental collapse.

The Maximalist:

The Maximalist will do anything to prevent confronting the reality that they will never be as whole as their photo wall is filled.

Their home also follows them around (there’s a theme here), but instead of shedding what the Minimalist would consider ‘dead weight’, the Maximalist hoards it. ‘Stuff’ is their favourite word. They find comfort in things. They love the sensation of getting lost amidst a pile of feelings and memories and nostalgia. As a child, they lugged every teddy and every Sylvanian family member they owned from one location to the other lest they spend a night with enough room in their bed to remind them that they are an ever-changing being that will never feel as grounded as they hope they will.

The Patrick Bateman:

The Patrick Bateman will do anything to distract themselves from recognising the need to attach their identity to a physical location. Acknowledging their emotional side is not something they’re equipped to do.

The notion of home has proved utterly useless to them, so why should they dedicate any time or effort to their living space? Their bedroom is not an expression of their personality but rather an expression of their sterile, pragmatic approach to life. Their rooms are places that serve a practical function. They sleep there, get dressed there, and occasionally make use of the excess floorspace to do yoga (they carry the weight of the world on their backs, it gets sore after a while).

When you consider what it might be like to decorate a room from an entirely practical perspective, the enormity of the task becomes apparent. It’s actually quite difficult to do, but the Patrick Batemans do it because they’re too busy doing useful things that will glow on a CV to focus on which pillow is fluffier. What do you take them for?

The Constant Makeover:

The Constant Makeover will do anything to avoid recognising that they want to feel pure, clean, maintained, and perfectly managed because their home life never was.

They find it impossible to establish control over their daily space except in sporadic 3am bursts of productivity, so they fixate on their own appearance instead. At best, they sunbed frequently and work out obsessively. At worst, they inject melanin before sitting in the sun and supplement their leg day with a less than healthy dose of trenbolone. Preening, plucking, waxing, shaving, skin-fading – nothing is ever enough. They chase the thrill of looking and feeling their best … for 24 hours until the maintenance routine starts up again. If for some reason they can’t get to the salon for whatever treatment they feel empty without, they’ll gorge on toxic TikTok content about the importance of buccal fat removal and drinking through a straw to minimise smile lines.

The Total Mess:

The Total Mess will do anything to procrastinate tidying because they fear that somewhere amidst the piles of rubbish, their inadequacies will emerge.

They have completely given up on making their house a home. They did try, though. At the beginning of each month they decided to finally commit to a laundry and vacuuming routine. Once a week is manageable, right? But alas, the energy drink cans and sweet wrappers pile up, the clean underwear runs out, and the blinds stay down. The living space becomes a hub of depression and, if they’re lucky, their mothers will get so sick of the sight of it that they’ll clean it regularly enough to avoid having to legally declare it a health and safety violation.

***

No one said divorce was fun. It’s not. Somehow the now grown-up children of divorce will come to make their peace with the physical tumult of their upbringings. They might absorb and become their surroundings, they might reject them completely. They might decide to cut the process short and go to therapy. Until then, they continue to be wacky decorators, tortured artists of their interior worlds (no pun intended).

There have been so many times over the past few years that I have been ashamed to be British. Tragically, this might just top them all. Quite frankly I am incredulous. It is hard to believe that this country is run by people willing to break human rights laws, willing to break the UN refugee convention, and willing to deny desperate people the chance to plead their case purely on the basis of how they have made their journey. But this shouldn’t be about breaking laws, the morals should be enough. The fact that this policy is unlikely to ever come into force almost makes it worse. It shows a government led by people willing to cast their moral duties and values aside with no obvious aim other than appeasing a select group of the electorate.

First let me lay out the facts. The new law’s first aspect means that anyone arriving in the UK by small boats or any other ‘illegal’ means will automatically have their application rejected and detained. Then, it will be the ‘duty’ (yes ‘duty’) of whoever is the Home Secretary to remove them to a third country such as Rwanda. In the future, those people will never again be eligible to apply for asylum in the UK, regardless of age, situation, or route. For the first 28 days of detention, migrants won’t even have the power to seek bail or appeal their decisions, effectively condemning them to detention regardless of how compelling their case is. Finally, there will be a new cap on refugees settled in the UK set by Parliament. Effectively at the moment this gives the Conservative government free rein to block applications regardless of global situations or individual cases on a purely arbitrary basis.

The messaging is almost as bad as the policies themselves. What does it say about our country that the Prime Minister is willing to put himself behind a podium that reads ‘STOP THE BOATS’? What does it say about our country that the last three tweets from that Prime Minister tell people in bold red lettering that they will be ‘DETAINED, DENIED, and BANNED’? On Radio 4’s Today programme this morning Suella Braverman had the cheek to say that this policy is designed around being humane. I don’t know what law she thinks she has put together and is singing the praises of but it certainly isn’t the same one I’m reading.

In terms of possible legal challenges, ‘problematic’ doesn’t even begin to cover it. Perhaps the one reassuring thing that Braverman has said in the past 48 hours was in her letter to MPs covering the law: here, she states that there is ‘more than a 50% chance’ that the law would be found to be incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights. In reality, the ECHR might prove to be the least of her problems. The rules she is looking to instigate clearly voilate the parameters set after WWII by the United Nations Refugee Agency in their refugee convention. The UNHCR said themselves on Tuesday that “This would be a clear breach of the refugee convention and would undermine a longstanding, humanitarian tradition of which the British people are rightly proud.” In essence, this particular breach is due to the fact that the law prevents refugees from making their case. We of course already know that Braverman is keen to leave the ECHR but to go a step further and break the UN Refugee Convention defies belief and sense.

The reality is that this, like many of this government’s policies, is pure showmanship. Clearly there is a problem with our asylum system but that problem is not refugees. Both short and long-term options do exist even if they are less flashy on a government billboard. It starts with admitting failings and tackling the backlog that just a few weeks ago topped 160 000 for the first time. In 2022, only 23,800 decisions were taken on asylum in a stalled system filled with inadequacies and costing the country £6 million per day in hotel bills. The response though needs to be wholesale reform and investment, not the emergency temporary measure of some applications being assessed abroad on forms exclusively available in English. After recent wins with the Windsor Concord, Sunak should also be looking at the only sensible long-term solution – the establishment of safe and legal routes. This approach has seen success with the establishment of offices in France with regard to Ukrainian refugees in the last year but there is no reason that this shouldn’t be expanded to prevent people from having to risk their lives in the channel. That, hand in hand with a re-establishing of the UK aid budget back to the 0.7% of GDP figure that had long been settled upon by all parties can tackle human tragedy at source and make a real long-term difference.

So, I hope and pray that this new law doesn’t come into force – early signs show that it almost certainly won’t, but that isn’t what is making me feel so disappointed in my country this morning. The kind of rhetoric from a Prime Minister who says he is ‘up for the fight’ against human rights laws and a Home Secretary that spreads the kind of dangerous rhetoric that she has in recent days is just plain wrong. This shouldn’t be about politics, this should be about moral duty.

Image: CC2:0//AndreyPopov via Getty Images/iStockphoto

Bangkok, the mid-2000s; sifting through crates of cheap, second-hand vinyls in record shops in Chinatown, one of the oldest parts of Bangkok, Chris Menist and Nattapon ‘Nat’ Siangsukon, aka DJ Maft Sai, came across the traditional Thai folk genres of Molam and Luk Thung. After falling in love with the genres, the two formed The Paradise Bangkok Molam International Band. The experimental band blend influences from traditional Thai folk music to psychedelic rock to Afrobeat grooves, exemplified at its best in their 2016 album Planet Lam.

Molam and Luk Thung originated in the north-eastern Isan region of Thailand, and Laotian and Cambodian borders in the 17th century. It is characterised by the khaen, a bamboo mouth organ which provides a warm, all-encompassing sound, underneath a vocal melody. This melodic style moulds to the tones of the lyrics, particularly effective as Thai is a tonal language. The most common additions in instrumentation are the phin, a lute-like stringed instrument, drums and bass. The genre underwent a shift in the 1970s as American GIs were stationed in the region, and they brought with them American popular music, from psychedelic funk to rock’n’roll. As musicians in the region entertained the soldiers, they picked up on these styles and began incorporating them with traditional elements.

Sitting in my room in Oxford on a dreary Tuesday afternoon seems worlds away from this thriving Bangkok music scene, which Menist vividly describes when I speak to him over zoom. He details his move in the early 2000s, as his wife found a job there, and he ‘did what I always do when I go to a place I’m not familiar with, I look for music’. The power of music realised, dare I lean into the cliché, as Menist elaborates on the connections he made with the record collecting community, including meeting ‘Nat’, the music scene in Bangkok and familiarising himself in this new setting. ‘Every country has their creativity and that manifests itself in music, literature, film, art’ and so on, he tells me, ‘people create out of who they are, that’s what they do … a populous is communicating to people, this is who we are, this is what we’re about, so if I can try and connect with that, then I think you’re connecting with something that’s very true about an environment’.

The band emerged gradually, beginning with ‘Nat’ and Menist’s Paradise Bangkok nights in 2009, at which they DJed, playing a ‘wide variety of music’ Menist elucidates, ‘we’d play our new discoveries basically’. They then established Studio Lam, which describes itself as ‘a home for creative new music’, and in attempts to form a kind of house band, they got in contact with some of the established Luk Thung and Molam musicians, evolving into the band as it is now: Piyanat “Pump” Chotisathien, the former bassist of the Thai Indie Rock band Apartment Khunpa, Sawai Kaewsombat on the khaen, Kammao Perdtanon, described as Thailand’s answer to Jimi Hendrix, playing the phin, Phusana “Arm” Treeburut playing drums and ‘Nat’ and Menist on percussion and production. Menist is careful to point out, however, that it was not as simple a process as it perhaps appears. Bringing together musicians from ‘musically speaking more rural background[s]’ and ‘from the city background’ was ‘not that easy’, but as they continued to rehearse and work together, they ‘really started to gel’.

The revival of this “forgotten” music has re-established the virtuosos Kaewsombat and Perdtanon. Perdtanon describes that after seeing Isan people holding phins and khaens whilst begging on the Bangkok streets, he felt inspired to ‘make all Thai people appreciate the phin’. All of this has been prominent in re-situating perspectives on the genres, once disregarded by middle-class urban Thais as ‘taxi driver music’, and has contributed to people feeling ‘less ashamed of Isaan-ness’. It is not only Thai people whom the band have inspired; artists from Mick Jagger to Damon Albarn have displayed their support, and the band have toured across Europe, including a set at Glastonbury, which Menist describes as a ‘tipping point … [it] definitely shifted some people’s perspectives’.

Menist is careful to highlight that the band’s music is, however, solely ‘our take on it’, they did not come to the genres with ‘an academic or aesthetic approach’, instead wanting ‘a band that would represent the type of Molam that we had played at the club night but a slightly more updated version’. They are in no way ‘suddenly representative of … the pure art of Molam’ which is ‘rooted linguistically, historically and geographically in the Northeast’. Some listeners from more traditional backgrounds ‘don’t like what we do … it’s something different’, Menist elaborates, ‘that’s fine, that’s ok …so in the same way that the music choice is very subjective … the band’s creations are very subjective as well … we wanted something that felt suited with the general stuff we were doing and that’s why it sounds like it does’.

Their 2016 album Planet Lam encapsulates this crossover, providing an introduction into the sound world of Thai traditional folk music, whilst blending an international range of styles. The album opens with one of the defining instruments of Molam and Luk Thung, the khaen. Described by Jotikasthira as ‘surreal’, it is this sound which provides Molam with its psychedelic feel. The journalist John Clewely emphasises the amazement expressed by foreigners when they first hear the instrument, in awe of its ‘big cathedral chords’. Surrounding the listener with warm, glowing harmonies, Kaewsombat opens the track, ‘Lai Wua – Chasing the Cow’ with an improvisatory-like riff on the khaen before establishing a tempo which the percussion gradually joins in on, followed by the bass, supplying an addictive groove. The adaptive ability of the khaen is exemplified on this album, as it binds syncopated cymbals and funky bass lines. Some may recognise the instrument from when it went viral on Tik Tok in 2020. Sampling Hal Walker’s ‘Khaen Rock’ the producer Llusionmusic paired it with a cloud rap beat and slowed and reverbed Playboi Carti vocals from ‘banakula’ which proved immensely popular, the sound used on around 129.6k video posts and played in the background of videos with millions of likes and tens of millions of views.

The album proceeds with the upbeat rock-like cut, ‘India Chia Muay – Thai Boxing Re-fix’, commencing with a phin solo. Influenced by ‘the urgency and drive’ of The Stooges, the cyclical phin weaving around the infective drumbeats, with tempo changes coming midway through, captivate the listener. The Stooges influence can again be heard on the fast-paced ‘Adventures of Sinsai’. If you find yourself running late to a lecture, I recommend listening to this on repeat, you will find yourself subconsciously speed-walking along to the track, albeit with some perplexed stares from those you pass. I probed Menist on this range of inspirations, wondering what the creative process looked like, whether influences were conscious or subconscious? ‘it’s subconscious’, he replied, ‘I think most music is made that way … no one can play like The Stooges except The Stooges of course’. He elaborated that this ‘side’ comes from his and ‘Nat’s ‘sensibilities’, the wide variety of records they play whilst DJing seeping into the band’s compositions.

More experimental, electronically focused tracks can be found in ‘Exit Planet Lam’ and ‘Exit Dub’. Combining dub, reggae, and industrial ambient classical influences, the sparse arrangements showcase producer Nick Manasseh’s stamp on the work. Fortunate that they are not under pressure to appeal to listeners on streaming platforms, Menist and Manasseh mix and master the recordings to reflect the band most authentically; ‘we’re not going to compress it to death just so it appeals to a Spotify scroller’. Menist does mention, however, ‘one funny thing’ as a track from their first album 21st Century Molam has far more streams on Spotify than any other, as a famous Game of Thrones actress (he can’t remember her name) mentioned it on her Instagram story. A ‘very surreal’ moment, but ‘nice obviously’, the power of social media and celebrity demonstrated once again.

‘Studio Lam Suite’ is the band at their best, an eleven-minute culmination of traditional and electronic influences. It launches itself with a trance-like phin solo, the free tempo providing an improvisatory feel. This evolves into chordal strumming, establishing a clearer tempo, with emphases on the 2nd and 4th beats. After five minutes of enthralling phin playing, showcasing the instrument at its most versatile, an electronic drone takes its place. Phasing in and out and complemented with samples of street noise, percussion organically emerges. Menist explains these samples come from a field recorder he used as he walked around the area of Bangkok where the Studio Lam Club is situated, recording ‘street [and] ambient noise’. The track was then mixed in London with himself and Nick Manasseh, and ‘took ages’, he describes, hinting at the complexity of combining acoustic recordings with electronic influences. A warm, introspective sound is constructed, comparisons ranging from Aphex Twin to Sade as the funky bassline and laidback groove come to the fore.

Although of course planning and rehearsing are essential parts of the creative process, Menist explains that their recordings aim to reflect ‘how we were at the time’, trying to make it ‘as organic as we can’, all aspects must be ‘real’. That being said, they are a live band, and ‘there’s a reason why we’ve played ‘Studio Lam Suite’ only once’, Menist comments. This balance between practicality and creativity is something that, to Menist, ‘all art is in the end governed by, the balance between that which is creatively possible and that which is economically feasible’. Recalling production decisions and the pressures of streaming platforms, Menist acknowledges that the focus on creative freedom is a kind of privilege, as the band does not form the main part of his, nor the other musician’s, livings. Ultimately, what is most important is that the recordings showcase the artistry of the band, without getting too hung up about perfection, ‘that’s a bit of a dead end … just because something is perfect, it doesn’t make it interesting or inspiring’.

Listening to 80s house hits such as ‘Missing You’ by Larry Heard last Sunday as I frantically tried to complete an essay on eighteenth century opera, my mind drifted to Planet Lam, and I couldn’t help but be bemused by the transgressive power of music. How is it that my brain connects this house groove from a Chicagoan producer to a band based in Bangkok? How is it that the khaen’s drone-like role in parts of the album remind me of Celtic folk instruments, such as the hurdy-gurdy? Perhaps it is simply an untrained ear finding similarities where there are none, but I can’t help but be enraptured by the globality of music, bringing people from across the world together. I asked Menist about this connection, who assured me I was not alone, recalling the moment someone came up and said they ‘loved this Irish music you’re playing’, although it was in fact Molam. He concluded, ‘I just think that is coincidental’, agreeing ‘there is something there’, but ‘what makes that connection I really can’t tell you … because those tropes exist in so many music forms’. Sometimes you can trace a sound, but with ever increasing globalisation, such sounds are ‘too widespread to know exactly where [they] began’.

The Paradise Bangkok Molam International Band “rooted in tradition, with an eye to the future”, seem to have just that, Menist revealing to me there is another album in the works which will “hopefully come out this year”. An exemplary of the international force of genre-bending, experimental music this album represents a kind of music in which boundaries are transgressed and influences intermingled, creating an intensely enjoyable, diverse listening experience. ‘Good Shit’, as the journalist Aaron Steine wrote, in a review of the album. If you are interested in listening to more of this kind of music, I am by no means well-versed enough in the genres, but I would recommend listening to ‘Nat’ and Menist’s compilations Sound of Siam Volume 1 and Volume 2, alongside the 2011 compilation Thai! Dai? featuring tracks by the Thai rock legend Sroeng Santi. Thank you also to Ome, a 4th year biologist at Magdalen, for introducing me to the singer Rasmee Isan Soul from the North-East of Thailand who combines Molam Jariang cultures with Western and African music, terming it ‘Isaan soul’.