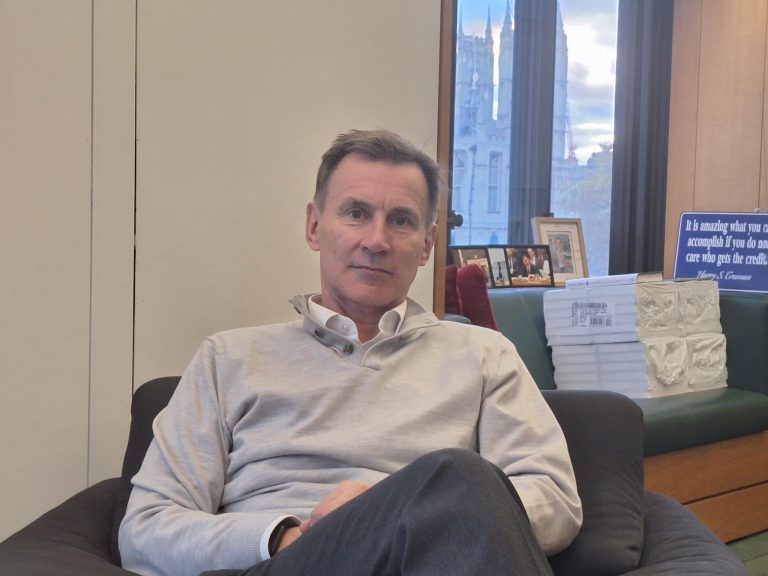

Cherwell: What was your experience of Oxford when you did PPE at Magdalen?

Hunt: They were some of the happiest times of my life, but there were lots of ups and downs. In my first year I struggled a bit, found it hard to make friends. I had such high expectations of ‘Oxford’ that I was a bit disappointed when it didn’t quite live up to what I hoped for. In my second year I found a great group of friends. I really enjoyed my subject. My main passion was actually philosophy, of the three. I also did university politics, I became president of the Oxford University Conservative Association, that was my first exposure to the sort of – madness – of politics. I made lots of friends who I’m still friends with today. I do think that studying at Oxford or Cambridge is one of the greatest privileges you can have because they are the only two universities in the world where you get the chance to sit down once a week, one-to-one, with one of the greatest experts in the world in the field you’re studying. That is an extraordinary privilege.

Cherwell: Would you say your time at Oxford shaped your trajectory towards politics?

Hunt: In some ways it slightly put me off. There was a lot of backstabbing in those elections, I’m sure that hasn’t changed. I think what you get in university politics is actually the worst of what you get in the real thing. In university politics, because you’re only president for a short period – say, a term before someone else comes in – people’s track record doesn’t count for much, you just have to be good at winning elections. Whereas, in the real thing, in Westminster, your track record does actually count for something –perhaps not as much as it should, but it does count for something.

Cherwell: Why would you say you entered politics?

Hunt: I didn’t give it too much thought. I was just really interested in political issues. I was at Oxford 1985-88 when Margaret Thatcher was at the height of her powers. She inspired me to do something first, which was to set up my own business. I was a kind of card-carrying Thatcherite, perhaps a bit more than I am today. I just thought the political world would be fascinating to be a part of, but I didn’t really understand the personal sacrifices that were necessary for a political career – the crazy pressure you can be under in certain jobs, the impact on family life, it is not a great career for families. I didn’t really understand any of that. Perhaps I should’ve given it more thought. Despite those downsides, I don’t regret a second of my career, and I do think there is no greater privilege than public service. That could be being a teacher or working for charity – not necessarily politics – but doing things that make the world a better place is a wonderful thing. Despite all the flack that politicians get, it’s worth it.

Cherwell: What’s your proudest achievement since you entered Parliament?

Hunt: I was in Cabinet for most of the fourteen years the Conservatives were in office, and I did four jobs. It’s just impossible to be around for that long without making a lot of mistakes. For sure I didn’t get everything right. Probably most people will remember me as the chancellor who came in during a crisis, when inflation was 11%, and got it down to 2%, got the economy growing again despite predictions of the longest recession in history. But if you ask me what I’m most proud of, when I was Health Secretary I was very unpopular – a 2016 YouGov poll put me as the most unpopular politician in the country, because of the junior doctors’ strike – but my focus was on patient safety, reducing the amount of avoidable deaths. During my period, the number of baby deaths fell by about two-a-day. I think that’s a statistic which for me personally I’ll be proud of until the day I die.

Cherwell: What’s your biggest regret in politics?

Hunt: What I’ve been doing is trying to write – I want to be a writer now – and as a writer you do reflect on things you got wrong. I think, looking back, that I was generally thought of as a safe pair of hands. As an entrepreneur, I was a radical innovator, and I think the system made me more of an incrementalist, and less radical than I would really like to have been.

Cherwell: So, your regret is more about things left undone than anything you did which you wish you hadn’t?

Hunt: When I was Chancellor, working with Rishi Sunak, I steadied the ship. We had less than two years before the end of parliament. I would like to have done more radical welfare reforms, which are badly needed, and which, sadly, it doesn’t look like the current government is going to do either. Whether Rishi Sunak would have wanted me to do them, I don’t know, but it’s much more about wishing I could have done more, perhaps with a bit more time, than regrets about things I actually did do.

Cherwell: When Labour won the election in 2024, you said, “Whatever our policy differences, we all now need them to succeed.” Do you think you made it more difficult for them to succeed when a few months earlier you cut National Insurance by 2p? It was an unnecessary pre-election giveaway which you must have known would create problems for the next government.

Hunt: Not at all. The biggest problem facing the country is low growth and those NI cuts were independently forecast by the Office of Budget Responsibility to increase GDP by 0.6%, which sounds like a small number but makes a big difference in terms of the tax receipts the Chancellor gets. That was my growth strategy; to reduce tax in ways that would get the economy growing. In truth anyone who criticises that, that’s fine, but they need to say what their growth strategy is instead, and I don’t think we’re seeing that from the current government.

Cherwell: Do you foresee a return to government?

Hunt: I really, passionately, want a Conservative government. I think as a country we only succeed when we have parties in power that understand business. All the things we want to do – funding the NHS, the police force, the education system – can only be done on the back of a strong economy. But I think it’s pretty unlikely that I will ever go back into government. Times move on. I think my wife might have something to say as well! But I want to contribute to public life and hopefully I can do that through my writing.

Cherwell: You’d ideally like to see the return of a Conservative government. Do you think that’s been made less likely by the fact that, a) a lot of the moderate wing of one-nation Conservatives were expelled in 2019, and b) the pressure from Reform has driven the current party further and further to the right?

Hunt: I don’t think so. I think we are a long way behind in the polls but you would expect that just over a year on from our worst-ever election defeat. Having been in office for fourteen years, the country clearly wanted a change. Even though Labour’s first year has been pretty disastrous, people won’t come running back straight away with buyers’ remorse. It will take time. What the Conservative Party is respected for is, time after time in our history, taking the difficult decisions to get the economy growing after some kind of crisis. I think as we approach the next election, that’s what people will be worrying about. They can see the mistakes that have been made by a Labour government. So, I think we will be back in the race by the next election. You mention Reform, but they have no economic credibility at all, and so this is our area of competitive advantage.

Cherwell: Which contemporary figure do you find yourself most in sympathy with, in politics?

Hunt: Now, that’s an interesting question. [Long pause] If you’re talking sympathy, I feel for Rachel Reeves, because it’s a pretty tough gig being Chancellor. I don’t agree with a lot of the stuff she’s done, but I do recognise it’s a very tough job. If you’re asking who I’m in sympathy with ideologically, I think I am very aligned with what the current Conservative Party is saying. I think that people want radical change and if we’re going to persuade people that we’re a better option than Reform, we have to embrace a rational radicalism. I think that some of the ideas that Reform are championing are very badly thought-out. We have to show people that we will deliver big change but that it will be thought-through change, not chaotic change. So, I don’t tend to look at everything through the prism of left and right. What people want is a leader who will give them confidence that they are actually going to be able to sort out the big problems that we face. Frankly, that’s a challenge for Labour as much as for the Conservatives. At the moment, people are worried that both parties are unable to tackle the big problems we face. For the Conservative Party, that’s what we’ve got to show everyone.

Cherwell: Moving onto your new book, Can We Be Great Again? Why a Dangerous World Needs Britain, a sort of memoir-cum-manifesto. What inspired you to write it?

Hunt: I think we have become too gloomy as a country. There are various reasons for that, but there’s a paradox which is that you can do surveys where nearly a third of young people want to move abroad and then you ask young people across the rest of the world what they think of Britain, and we are considered the third most attractive, appealing country in the world, after Japan and Italy. We are the second most trusted country in terms of its government and people. When it comes to the country that’s a force for good in the world, we’re rated top in the world by 18-to-34-year-olds surveyed across G20 countries. There’s a disconnect between how we see ourselves and how the world sees us. I wrote this book to understand who’s right.

What I found when I was Foreign Secretary was that we are much more respected than we perhaps understand in the UK. After the Second World War, Britain and America set up a global order which has been the most successful in the history of humanity. It has been better at reducing poverty, maintaining peace, helping people to live in freedom, than any other order – that is until quite recently, with big problems in Ukraine, and the rise of China, which is an avowedly autocratic system that doesn’t share our democratic ideals. In my lifetime, the proportion of the population living in extreme poverty – which is defined as less than $2 per day – has fallen from half the world population to only 10%, and that too in a period where the world population has tripled. That’s an extraordinary achievement but people are saying, “is this going to continue?”, they’re looking to the countries that set up that order, saying, “are you going to step up to the challenge?”.

This book is not a jingoistic book. I’m not saying that Britain is superior to other countries. I’m saying that in a really dangerous world the worst thing is to underestimate your own influence and that we – and the same is true of the Germans, the Japanese, the French, Americans, and Australians – are countries of influence and we need to use it. We need to work with our friends and allies around the world to solve these big problems.

Cherwell: You speak about our place in the post-war world order, and in the book, you talk about the position we should have in promoting democracy, security, human rights. Do you think these values are undermined when in world affairs we do not practise what we preach? Most recently, it’s been in the Middle East, but that hypocrisy has been there since the early days of the liberal international order. To give the example of a friend who you praise highly in your book, Henry Kissinger in the 1970s helped overthrow a democratic regime in Chile and killed hundreds of thousands of Cambodians through carpet bombing. That doesn’t sound to me like either democracy or human rights. Don’t you think things like that undermine the American-led world order?

Hunt: For sure, we haven’t got everything right. Sometimes we are hypocritical. But remember that in the 1970s and 80s, during the Cold War, we were up against the Soviet Union that was actively trying to subvert regimes all over the world and turn them into part of the Communist bloc. When you’re dealing with a threat like that, there are trade-offs. It’s not possible to conduct a foreign policy where all you think about is talking to people with exactly the same values as you. You need to deal with the world as it is, not as you’d want it to be. I think there is a world of difference between what Britain and America did in Afghanistan and Iraq and Libya – where we made big mistakes – and what Russia is trying to do in Ukraine. We’ve got things badly wrong in all those three countries but we were never trying to turn them into imperial possessions, it was always the plan to go in, install a democratic regime, and then leave again. We were naive and made big mistakes and we need to learn from that. That’s not the same as what Putin is doing in Ukraine by invading an independent country and turning it into a vassal state. I think it’s a big mistake to conflate those two and we should be very clear about the difference.

Cherwell: Clearly there’s a difference between Britain and Russia insofar as we didn’t invade Iraq to make it an imperial possession again, but surely you can see why these wars, and their enormous human cost, have delegitimised the West and its world order.

Hunt: Yeah. For sure. When you make mistakes, you lose moral authority. And that means that we go into this global struggle between autocracy and democracy not being in as strong a position as we might otherwise. Despite that I think it’s important that we don’t lose confidence, that we recognise that our system is better, that open societies are morally superior to dictatorships in which people who disagree with the government get locked up. And it’s really important that we don’t forget that basic truth. The evidence is that, in the global migration crisis, people aren’t banging the door down to become Russian citizens, they’re not trying to get into China. They want to live in Europe and North American and Australia and Japan and Korea, because they know that for them, and their families, our system is more humane. One of the things Henry Kissinger said to me is that his concern about the West was that there was so much self-doubt, even self-loathing, and we need to be really careful not to let that get out of hand.

Cherwell: On China and the need to stand up to their autocratic system, you’ve spent a lot of time in China, what do you foresee in the years to come in its relationship with Britain and the West?

Hunt: We’ve had this rather fake debate between hawks and doves. I think the truth is that both sides have a point. The hawks are absolutely right to say you need to be strong because that’s the language that autocrats respect. The doves are right to say we need to keep talking to China, because we’re not going to bankrupt them as we bankrupted the Soviet Union in the 1980s. It’s a formidable economy and it’s growing very fast. There’s no solution to global problems like climate change without having discussions with the world’s biggest emitter. We need to talk to China but do so from a position of strength. We need to recognise that there is a global struggle between democracy and autocracy. Only 20% of the world’s population lives in fully free countries, according to the American think tank Freedom House. When it comes to flying the flag for open societies, the UK is one for the most influential countries on the planet: our universities are the most respected in the world outside the United States, we educate more foreign students than anywhere outside America. Our media, whether its the BBC or the Financial Times or the Economist, is read all over the world. That kind of makes us a global leader in washing our dirty linen in public, because when something goes wrong in the UK everyone knows about it. But we, in truth, have a big influence in how that argument unfolds, and I think that we should stand up for our values.

Cherwell: In the book you talk about the UK’s path as the next Silicon Valley. What do you think is the path forward with that, and do you welcome, for example, the Oxford-Cambridge Silicon Valley which the government is trying to create?

Hunt: I do. In every speech I gave as Chancellor I said that Britain should aim to be the next Silicon Valley. The new government has endorsed that, they say they want us to be an “AI superpower”, but it’s the same vision. I think the first thing to ask is, “why with all the problems Britain has, are we not being laughed out of court when we say these things?”. The reason is that people can see we have a couple of really fundamental strengths that are difficult for other countries to imitate. The first is that, as the most respected universities and biggest financial centre in the world, outside the United States. This means we have the most extraordinary ideas which are now coming out of science parks, business parks, Oxford, Cambridge, Imperial, and many major universities. Ten years ago, you’d only find those business parks in the Ivy League universities in the US and Stanford. Now we have them everywhere in the UK. Ten years ago, you could say that Britain was really good at inventing things, but it always ends up being commercialised by the United States, but now we have more unicorns than France and Germany put together.

Cherwell: What are you writing next?

Hunt: It’s an interesting thing, writing. When you do a job in government, let’s say you’re Health Secretary, you know nothing about the NHS, but you’re answering non-stop questions about it day and night. You get quite good at answering these questions and after a month or so you think you’re quite an expert. It’s only when you sit down and write a book that you find all the gaps in your knowledge. I want to write optimistic books that give solutions to some of the big problems we face. The book I published this year, Can We Be Great Again?, is about Britain’s place in the world, trying to answer the question of whether we can be a great country. The next book will be about how to fix the economy and I want to write an equally positive book that says the problems of economic growth are intrinsically solvable. If you like, Can We Be Great Again? is the book I wish I’d been given on the day I became Foreign Secretary, and the next one is the book I wish I’d been given on the day I became Chancellor.

Jeremy Hunt’s new book, Can We Be Great Again?: Why A Dangerous World Needs Britain, is available now from Swift Press.