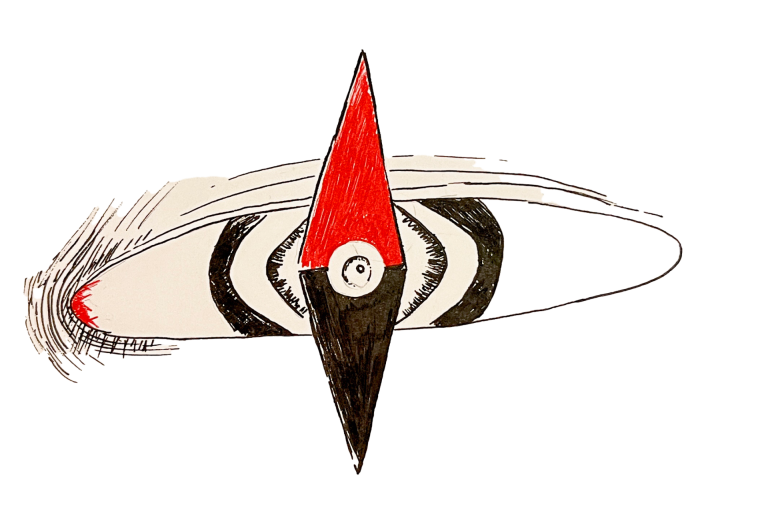

When I first walked into Exhibition 004, my gaze was immediately met with Magda Adamczyk’s Nightmare. A demon, swirling with hellish strokes of red, stared at me. The demon invades. It conquers the viewer’s mind, through the floral dream of the foreground, and then swallows them all into the darkness, tongue first.

To escape, I glanced rightward, chasing a way out of the nightmare, and Aman de Silva’s Window Shopping installation of garments and printed photographs roused me awake. What particularly caught my eye was a shirt – wet-looking and glistening, as though it were still clinging to a rain-soaked body. De Silva told Cherwell that he achieved this effect by moulding a shirt to his body with slow curing epoxy resin. Next to it, a Union Jack fashioned dress and waistcoat – “bizarre white middle-class British uniforms”, De Silva told Cherwell – both white-colored and contrasted against brown. De Silva said this piece was inspired by the “anti-immigration riots” which generated a dissonance in his once-comfortable British-Indian identity. And thus, De Silva uses this piece to navigate these emotions, through the use of the themes of brownness, whiteness, uniforms, and performance, rewriting his own sense of self through his artistic innovation.

Visual Arts Worcester’s Exhibition 004 showcases art across all forms and mediums. While being only two artworks in, I began to think that I was already knee-deep in its immersive diversity. However, unbeknownst to me, the exhibition had already begun before I even knew it. Upon entering Worcester College, I passed a cello drawing made against the cloisters. Lewis McCulloh, president of the Exhibition 004 committee, told Cherwell: this was a “live drawing from the launch night”, a symphony of lines created by Rowan Briggs Smith in collaboration with the playing of cellist Matthew Wakefield.

Tiger Huffinley, Head of Installation, told Cherwell: “there was a large variation in the mediums.” As a result, a priority of the exhibition was to find a configuration that would make the pieces complement one another. Huffinley also told Cherwell: “we were lucky with the space we were given to make that happen” – that is, the Sultan Nazrin Shah Centre in Worcester. The idea here is to integrate the diverse mediums and thereby create a sense of balance.

The concept of culture and identity is prominent in Exhibition 004. Right on the mark is Camilla Albernaz’s photograph Carnival in Salvador: A Celebration of Culture and Identity. The outsider is dropped straight into Salvador’s Carnival, a deeply rooted Brazilian tradition, becoming another among the colorful, laughing, singing people. The photograph calls both sonder and oneness to mind; the people dance together yet each to the sound of their own respective tunes. “I aim to offer a new perspective of Brazil”, Albernaz told Cherwell, “one that reveals the strength of a community which, even in the face of historical inequalities, reclaims public space.”

Lisha Zhong, too, reflects identity and culture in the eye-catching piece Like a thousand cranes. The artist used their mother’s suitcase to build a bridge between British soil and their ancestral Chinese home. Inside the suitcase, Chinese immigration cards hang from a laundry rack, airing out their lineage in the sun and illuminating it. But as Fern Kruger-Paget’s My F**king House shows us, in the form of polystyrene and knitted panels, displacement, at all levels, is never easy. Kruger-Paget told Cherwell that the piece was created after receiving news that their family had to move out of their childhood home, which “sparked some incredibly intense emotions.”

Our memories can then be begged by Kian Swingler’s Witnesses: He organizes photographs of memories – loving and painful, unforgettable and forgotten – on white fabric, hung in the air with red string. These memories make us who we are. In the same vein, Oliwia Kamieniecka preserves their memories as visual poems—this is uniquely shown through Sand Alphabet, a 16-second stop motion animation completed on a printer scanner and displayed on a television. Paper bag poems are just as enthralling: Julia Strawinska suspends memory in time, the clock hands pointing to the liminal space between love and pain. Julia, too, speaks of dreams, but in all capitals this time: “…I’VE BEEN DREAMING OF YOU ALL SUMMER.”

The exhibition makes space for the anatomical, the scientific, and the mathematical. Untitled by Alice Byfield is a gory self-portrait that pulls skin back to reveal the sfx beneath, autopsying the sensation of losing oneself to plastic surgery. Se Lyn Lim’s Anastasis draws from the titular Greek word, meaning ‘resurrection’, by showing a bizarre hybrid organism emerging from a shell in a fashion reminiscent of Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus. Cici Zhang’s Notes from a Nervous Hand pleasantly surprised me with its use of recycled handwritten notes and mathematical scribblings, a novelty I would love to see more of in art. The viewer can also find a number of ornate pottery pieces from the Oxford University Pottery Society throughout the exhibition.

Finally, I end this exhibition with a journey around Luke Hewson’s series of photographs entitled Winter at Worcester. The artist captures Worcester in the snow at the tail end of his first ever Michaelmas. The photographs create an immersive experience; they drew me in, making me feel as though I was there when they were taken. This piece quietly reminds us what a privilege it is to be at Oxford, surrounded by all its beauty and creativity.

To me, Exhibition 004 is a love letter to the raw artistry that comes out of this city, from both students and other artists, and it bleeds through every canvas, stitch, and shutter-click.