Oliver never intended to become a full-time content creator. He originally created his TikTok page to market his queer fashion brand, launched in the year preceding his master’s degree at Oxford. “I wanted to start an eco-friendly queer fashion brand because I had noticed that there weren’t really any specifically queer fashion brands out there. It was all people putting a rainbow on collections for pride.” It was only when he moved to Oxford and was offered his first brand sponsorship – which he admits was “way more lucrative than selling a few t-shirts” – that he decided to focus solely on making Oxford student content.

Although Oliver has accumulated a well-deserved 770,000 followers on TikTok, he tells me that the street interviews which have made his name were not always the easiest type of content to make. “I hated going up to people and asking like, excuse me, would you mind being in an interview […] it was always much nicer when someone willingly volunteered rather than being ambushed in the street”. This initial reluctance stems from the “unethical” approach that he believes some street interviewers take. They ask questions “designed to catch the people being interviewed out”, something which Oliver is both cautious and critical of. “When people run up to someone and shove a microphone in their face … incredibly unpleasant. Or when they interview drunk people late at night … also incredibly unethical […] People are wary of street interviews. I think, justifiably so.”

Since his following and the popularity of his content have grown, it has become increasingly easier for Oliver to find willing participants for his interviews, with many students, hopeful for a feature, messaging him on Instagram or approaching him in the streets. This enthusiasm is undeniably a testament to the skilfulness and poise which Oliver brings to each of his interviews. He explains to me that the key to conducting a successful interview is all to do with range, curiosity, and spontaneity:

“Although I’m not an expert in many topics, I have a decently broad range of interests and knowledge that someone else is usually an expert in. This means that I can ask them fairly insightful questions. […] I think letting the interviewee shine helps to make a really good interview; the interviewer using their knowledge and experience to help shape the interview in a way that gets the most out of the interviewee’s brain onto the screen”.

He adds, “the other thing that I think I’m quite good at is coming up with something witty on the spot that helps keep an interview light-hearted when it might be, you know, a difficult topic to get to grips with”.

As an aspiring TV presenter, these are skills that Oliver hopes to one day put into practice beyond the context of his TikTok videos. “There are people at the BBC that I meet, and they’re like “I love your videos!” And I’m like, well…I’m here… I can do this for the BBC… And they’re like, “yeah, totally, definitely” and I never hear from them again”. While appearing on TV remains the end goal, for now, Oliver is happy to concentrate on social media and has many ambitions for what his content could develop into. He tells me that his dream collaboration is, perhaps unexpectedly, with the Olympic Games:

“This might be kind of controversial […] I feel like Olympics committee come under a lot of heat, and I haven’t looked into this, so don’t come at me, but collabing with the Olympics would be so cool. This definitely sounds braggy but in the same way that I have quite a good breadth of basic knowledge of things to help me with interviews, because I’ve done a lot of sports, I’m also quite good at picking up the basics of a sport quite quickly. […] I think Niall Wilson did a did a series a while ago that was like him and the National Lottery. He was trying loads of different sports like BMXing, ice skating, those kinds of things. A series like that where I’d get to collaborate with Olympians, showcasing a load of different sports, interviewing them about the sport and about their life as well would be so cool.”

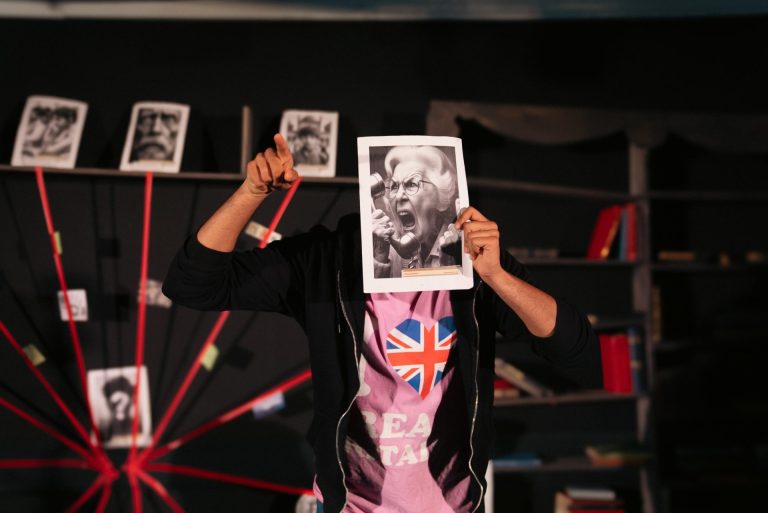

It was actually during his training sessions with the University of Oxford’s gymnastics team that he became friends with the (in?)famous ‘Bartholomew Hamish Montgomery’. They made a few comedy videos together where they parodied American and British stereotypes, the most popular of which was, unsurprisingly, the ones which featured the character of Bartholomew. “It was funny, we found it fun, it did well online, so we carried it on.”

Considering Oliver’s immense success as a street interviewer, it would be easy to forget the real reason he came to Oxford: his postgraduate studies in Law, which he first began at undergraduate level at the University of Durham. Since Oliver frequently interviews master’s students about their respective areas of research in his videos, I was naturally intrigued to hear about his own field of study, which he seldom discusses online. “I really should talk about it but it’s contentious in an algorithmic sense, so I don’t, and I’m always a bit scared. It’s quite vulnerable to talk about my own research. When it’s other people’s stuff, if it does badly, it’s fine but if it’s my own stuff doing badly, I’m going to be like, ‘oh no, people hate me, I’m really boring’”.

I was interested to discover that social media sites such as TikTok are also at the core of Oliver’s academic work. Yet, instead of comedy videos or online interviews, he is looking at a very different way in which these apps can be used : vaccine disinformation. Complex ethical and legal questions regarding governmental censorship, regulations regarding the spread false information, and the dangers of social media sites’ algorithmic nature underpin Oliver’s area of interest. “Can we regulate [vaccine disinformation] legally? Should we, philosophically? When you’ve got that toss-up between free speech and the public health interest of not being bombarded with fake information, where do you draw the line? Who should be to blame for that? Should it be the individuals spreading disinformation intentionally, or should it be the platforms for allowing that kind of stuff to get such a wide reach?”

He blames the social media platforms, an opinion which prevents him from discussing his research online, for fear of receiving backlash from the very platforms on which his income relies. He partially agrees with my question of whether there is a conflict of interest for his career to be dependent on a platform which he finds problematic in many respects. “[Social media] is like dynamite, right? It can be used in a good or a bad way. It can be used to blow up quarries and extract materials, or it can be used to kill people. But you can definitely use it for good. And I like to think that my content is largely quite positive. And so, because I’m using it in the good way that social media can be used, I like to think that there isn’t too much of a conflict of interest. Of course, you could take the more extreme view of ‘well, social media apps are objectively harming people. So, you shouldn’t engage with something that can harm people’. I think that’s probably not nuanced enough of a view.[…] And I mean, you know, when you operate in a society, everything’s always going to have a conflict of interest. But hey, we don’t think about that too much”.

Despite finding his legal studies both interesting and rewarding, Oliver doubts the possibility of pursuing this as a career path. “I think most Oxford students will probably relate to this: life is short and there are so many different things that would be fun to do. But you can’t do all of them. I think I would have had a perfectly happy life as a barrister. But I went into social media, and that was really, really fun. I want to do this for as long as I can and hopefully turn it into TV stuff”.

Before drawing the interview to a close, I ask him what advice he would give to students hoping to pursue a career similar to his own. “Well, first of all, I’d say stay away from the Oxford interviews. That’s mine. Get your own thing”. He is only half joking: he explains that this element of individuality is necessary for success as a content creator. “Part of the reason my stuff works is because I’m the only person that’s doing these university student interviews. You need to have something that makes your content stand out.”

His second piece of advice: “Don’t be afraid to be cringe. Like, it’s got to be a bit embarrassing to the people that you’re close to because in social media, everything is larger than life. It’s not going to be a truly accurate representation of what you’re like outside of social media, so it should make you cringe because you know you’re not really like that”.

I obviously couldn’t end the interview with Oliver without asking him the same question which has repeatedly featured in the most viral of his videos: ‘Which subject is the biggest red flag?’

He half-regretfully admits that “it might have to be law. There aren’t a lot of positive things to say about lawyers, if I’m totally honest. They spend most of their time arguing, sucking money out of the economy and it’s like, nobody wins in a lawsuit, except the lawyers. […] And there are so many lawyers that are only interested in the law and have no other interests. That’s fine if your subject is cool. But like, how, the law of restitutions has changed between, 1950 and 1960 isn’t a fun topic to be interested in”.

There wasn’t enough space for me to list the remainder of his qualms with his legal cohort but “argumentative”, “really good at complaining”, “conditioned to overanalyze everything”, among other deprecations, came up. Apologies to any law students reading this, but I felt his case was well-argued.