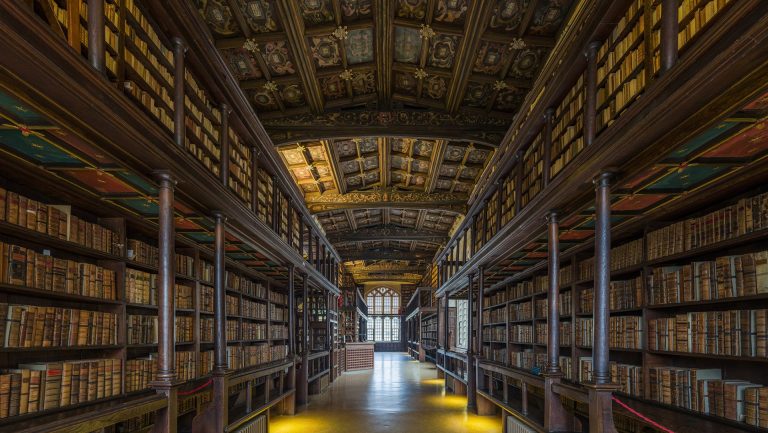

When my college denied me permission to perform Chinese music at its Lunar New Year-themed formal dinner last year, I initially accepted the decision. I was a wide-eyed fresher, awestruck by Oxford’s tradition of formals, where fellows strode through our 500-year-old hall to sit at the High Table. Their dark gowns billowed, and their Latin grace sounded impeccable.

Music could not ‘affect’ the High Table, I was told by the college’s email. Who was I to challenge a blanket ban on music?

Days later, my college hosted a Burns Night formal where a bagpipe brightened the hall. A student recited ‘Address to a Haggis’ and stabbed the titular dish at the High Table. It clicked, then, that the ban on music was rather a ban on non-traditional music. Under the hallowed spires of Oxford, that meant non-white music.

It hardly mattered that the instrument I’d played for over a decade, Guzheng, had 2,500 years of history. Its very name meant ‘ancient zither’.

New York City, 1834

Afong Moy was the first known Chinese woman in the US, imported to the East Coast as a teenager in 1834. Traders exhibited her in a box of Chinese artefacts, and curious Americans paid to see the spectacle advertised as ‘The Chinese Lady’. Wearing ethnic garments, she demonstrated speaking Cantonese, using chopsticks, and walking on her four-inch bound feet.

As Afong grew out of her teens, one of her replacements was Pwan Ye-Koo, a 17-year-old girl who played Pipa, the Chinese lute. In a pamphlet advertising her exhibit, Pwan gazed forlornly, hugging her instrument to her chest.

Thus the history of ethnic Chinese instruments in the Western world began as specimens of an exotic race.

In my imagination, Afong and Pwan were fiercely curious about the world. They learned English and devoured books backstage in between shows. When they grew too old for the exhibit, they travelled the country by railroad, making American friends and seeking out their countrymen.

But it is unclear what really became of the Chinese ladies. All I know is history and Hollywood remember their owner, PT Barnum, as ‘The Greatest Showman’.

San Francisco, 2014

When eleven-year-old me stood before the immigration officer at San Francisco International Airport, fresh off a one-way flight from China, I carried a half-size Guzheng on my back. I practiced and performed over my middle school and high school years in the US, everywhere from street corners to theatres that sat thousands.

I learned that being a musician of an ethnic instrument in the Western world means shifting between positionalities: either an echo of the familiar to co-ethnics, or an overture to the unfamiliar for others. To an audience of co-ethnics, I bring the melodies of home – and I will always recall the hunchback Chinese immigrant whose wrinkles stretched into a smile when he heard Guzheng for the first time in decades. But to an audience who never knew of Guzheng’s existence before, I’m an ambassador with only one shot.

In a position to shape their perception of ethnic Chinese music, I wondered whether I was perceived like Afong and Pwan. I’ve been told that every song I play sounds like Disney’s ‘Mulan’ soundtrack, or that Guzheng is cool but not an ‘actual instrument’. I learned it’s pointless to look for an ‘other’ category in prestigious music competitions the way I can find my foodstuff in the ‘world’ aisle of a supermarket.

I suspected that whenever I performed, I was not judged the way piano or violin players are judged for their skills. Rather, my pentatonic tunes were an exotic curiosity for ears acclimatised to Western scales. I was a breathing museum audio guide.

But unlike an artefact in a box, I was learning English, so I began speaking alongside my performance to put my music into context. From delivering a guest lecture at my local university, to national public speaking competitions, to TEDx, I presented the rich heritage of Guzheng and told stories of the Chinese ladies.

Oxford, 2023

At age 19 I carried my Guzheng through the immigration point at Heathrow International Airport en route to Oxford University. Here, I had no intention to stop my multi-year tradition of putting on Lunar New Year performances – until I learned that my music was deemed unsuitable for the High Table I so revered.

I cried in my room when I learned of the differential treatment between white and non-white music, for a formal meant to celebrate my most important holiday. It came as a shock in a college I’d found welcoming in every way.

I’d never felt excluded until then, but I guess that’s because I’d been the perfect image of an assimilated immigrant. I received high marks in PPE, edited the newspaper, rowed, and held office in student democracy. I spoke and thought in English, quadruple-underscoring the American half of my Chinese-American identity.

But I also teach friends to fold dumplings and decorate my room with red paper cuttings, drink hot water and wear slippers at home. I’ve been expressing myself through Guzheng longer than I’ve been expressing myself through the English language.

My college’s decision was one of many instances of institutional inertia in Oxford, where no specific person holds malice, but that the general reverence of tradition implicitly excludes students from non-traditional backgrounds.

Yet when I wanted to give up, my peers rallied behind me. They told me to speak up and supported me along the way. The JCR President met with the college registrar, and I sent emails to the don who represented the High Table – it turned out he was delighted to see a Guzheng performance, contrary to what the college told me.

We won. At last year’s Lunar New Year formal, I performed ‘Ode to Spring Breeze’ – my own solo arrangement of my favourite musician’s composition for a Guzheng and piano duet. Portraits of all the college’s presidents gazed upon the hall that night. In my imagination, Afong and Pwan were watching too – they watch over all the Chinese ladies, the first ones who forge a tradition in a new place.

I’d set a precedent so that another year, for another cultural holiday, another ethnic instrument may grace our 500-year-old hall.

Turning the (high) tables

Now halfway through my time at this historic university, I never cease to be awestruck by all the traditions – the sub fusc, the punting, the academic enquiries. I adore this year’s Burns Night formal, where I cheered for the bagpipe player and the Haggis addressor. I’ve been asked to reprise my Lunar New Year formal performance too, and so I will, in addition to performing at the Oxford Union and the Town Hall.

My music doesn’t destroy tradition. It is traditional. Precisely because I love Oxford’s traditions, I’m inviting my culture to be part of it.