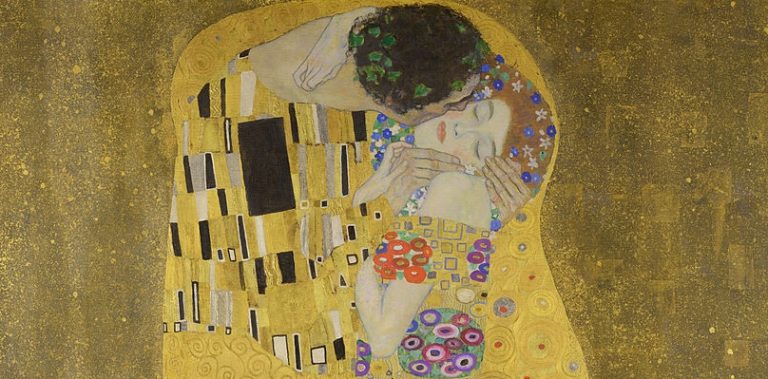

Love, betrayal, justice, jealousy: these are timeless themes, woven into the human experience for millennia. It’s no surprise, then, that they have shaped our literature for so long. They reappear time and time again, in the works of Homer and Shakespeare, Dickens and Austen, Orwell and Woolf. They never grow old – and why should they? Humans haven’t fundamentally changed. So why should our stories?

Retellings permeate culture. From operas to ballets, films to theatre, and novels to children’s fairy tales, we are ceaselessly reshaping the old into the new. In childhood we absorb these familiar stories unawares. The Lion King (1994) borrows from Hamlet; West Side Story (1961; 2021) replays Romeo and Juliet; She’s The Man (2023) took inspiration from Twelfth Night; and Gnomeo and Juliet (2011) – well, that one is admittedly less subtle. Even The Chronicles of Narnia offers a mythic, if loosely rendered, retelling of Christian scripture. Later in life we encounter retellings in more nuanced forms: Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea reframes Brontë’s depiction of the madwoman in the attic of Thornfield Hall, while Percival Everett’s James interrogates Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn through a contemporary lens.

But even translations are, in my view, a form of retelling. Translations do not map onto the original word-for-word; there is (as those of us who know the tribulations of translating can well attest) no accurate method of mechanical linguistic translation. Direct translations sometimes simply cannot exist. There is no precise equivalent to the Spanish ‘sobremesa’, the Portuguese ‘saudade’, or the German ‘Waldeinsamkeit’ in English. Each term encapsulates unique cultural experiences.

Translating, therefore, does require some degree of interpretive intervention. The philosophy of the translator shapes just how far the extent of this revision goes. Character names, idioms, and story structure may be recalibrated to align with new audiences. This element of retelling holds true even within a language, as older texts require adaptation to remain compelling. Seamus Heaney’s acclaimed take on Beowulf is illustrative of this: it is widely regarded as both a translation, and a reinvention. Poet Andrew Motion described it as “a masterpiece out of a masterpiece”, testament to the creativity required for such a project.

But why do we continually retell the same stories, repackaging them for new audiences?

Much of our love and affinity for such stories is rooted in what may be termed the ‘Volksgeist’: the cultural consciousness or collective spirit of a people. More precisely, it stems from the workings of cultural memory – the shared body of references, knowledge, stories, values, and symbols passed down through generations. These stories help to shape how a society views itself, and how it is remembered. Cultural memory not only anchors identity, but also articulates the overarching characteristics, values, and anxieties of a given historical moment.

A quintessential example of this phenomenon is the Grimms’ Fairy Tales collection. Originally published as the Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales), in it the brothers compiled a vast variety of stories. Today, it is often regarded as a collection of fantastical bedtime stories, but this project was more ambitious. In early nineteenth century Germany, still composed of disparate principalities and remnants of the Holy Roman Empire, these stories preserved and generated German folklore and culture, contributing to the growing sense of national pride and shared heritage. Many cultural historians often emphasise this cultural nationalism in Germany’s eventual unification of 1871. Preserving our stories, then, is not merely nostalgic – it sustains identity, and it evolves with society.

Recasting canonical stories within contemporary settings serves a crucial mediating function: it renders them more digestible for modern audiences whilst preserving their thematic core. From modern ‘No Sweat Shakespeare’ translations to dystopian retellings of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, such adaptations bridge centuries. In this sense, adaptation becomes survival – a Darwinian transformation that ensures lasting relevance.

Retellings also allow for a re-examination of older ideological assumptions. Gender, race, power, and identity can be interrogated through a modern lens. For older literature to remain resonant, it must be recontextualised for today’s values – carving out space for female agency, pluralistic identities, and postcolonial voices. This is particularly pressing during the digital age, where literature competes with podcasts, streaming, and social media for audiences’ attention. Reinvention rejuvenates the relevance of a work by adapting to the sensibilities of new generations. Though these stories persist due to narrative strength, their longevity depends on their capacity for transformation.

So it seems retellings of our stories do indeed have true intrinsic value. They may serve a modern audience, provide access to a story for speakers of different languages, or reimagine and revitalise popular literary worlds of the past. Most importantly, in my view, they provide us with familiar characters. This allows Jungian archetypes to appear time and time again and become recognisable to the collective unconscious. Jung held that humans possess an innate understanding of universal symbols (archetypes), such as Order, Chaos, Light and Darkness. Whilst I do not agree that we are born with innate recognition of these symbols from birth, I do believe retellings of stories are important in curating such archetypes anda shared ‘Volksgeist’ which shapes our society and relationships.