“Look.” A voice whispers – slowly, sensually.

White curtains quiver in the non-existent breeze that haunts the clinical interior of the Hayward gallery. With that slight movement, too, the image projected onto the curtain sways – Victoria Sin’s wide eyes flicker involuntarily as the camera slowly zooms into their face. In sparkling lingerie and full drag inspired by Cantonese opera, the model, laid out demurely across a satin curtain, stares back at the starers; sometimes sultry, sometimes vulnerable, always, somehow, piercing.

“Look. Look. Look – At her.”

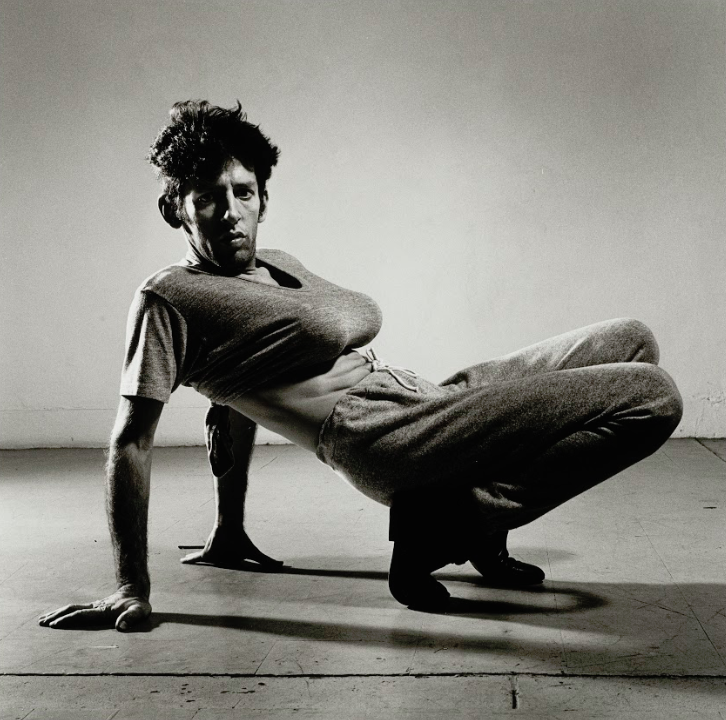

Victoria Sin’s A View from Elsewhere, Act 1, and She Postures in Context, three film-art pieces projected onto a curtain-enclosure, embody the spirit of the Hayward’s latest exhibition Kiss My Genders. The exhibition, made up of over a hundred artworks by thirty different international artists, centres around gender identity and fluidity. Physically enclosing their viewers in the wavering medium of cloth and projection, Sin appears to comment on the insubstantiality of gender boundaries, but in subverting perspective and viewing experience, also draws attention to the role of performance, presentation and spectatorship in all elements of identity. Hayward claims the exhibition focuses on “content and forms that challenge accepted or stable definitions of gender.” Paintings of hunter-gatherer tribes with drag elements question the West’s suppression of third-gender narratives, while sculptures made of artificial oestrogen and testosterone break down, biologically, what it means to be “male” or “female”.

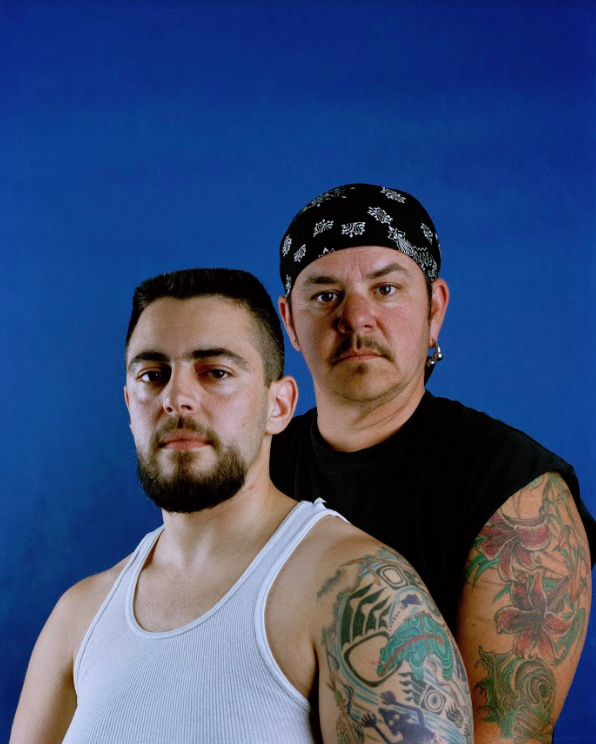

But more than just gender identity, the exhibits are an expression of the individuality and the internal or cultural conflicts of the artists. Amrou Al-Kadhi teams up with Holly Falconer to explore what he describes as the “disorienting” experience of being drag as a person of Muslim heritage by modelling as drag persona Glamrou wrapped in a Persian carpet. Cloned in different poses through triple exposure to express the incongruence of these disparate cultures, Al-Kadhi demonstrates their successful unification in the persona of Glamrou. Meanwhile Juliana Huxtable’s photographic self-portraits deflect identity-labels entirely; using makeup, costumes and fantasy backgrounds, she deflects the reductive categorizations ascribed to her as a “black intersex artist” by creating personalized embodiments of mythology, sci-fi and super-heroes. Kiss My Genders thereby becomes an exploration not only of the boundaries perceived in gender – but of individuals’ cultural identity experiences.

With this exhibition, an art assistant explains, the Hayward is attempting to break the mould of LGBTQ+ and gender-related exhibitions, which often focus on the violence and oppression experienced by these communities. Instead they want to celebrate different identities. Nonetheless, the exhibition is palpably political: Zanele Muholi explores black lesbian and transgender experiences in South Africa through photography – and acts of violence are still an all too present component of that. In her series Crime Scenes she stages the aftermath of brutal murders, photographing the upturned feet of model corpses buried in sheets of plastic and litter. Paintings like YESSIR! Back off! Tell me who I am, again? combine illustration and collage to satirize the way gender transition is spoken about. The artist, Flo Brooks, depicts a fictional cleaning company scrubbing away at a therapist’s room, reflecting his experience of the “hygienic spaces” he experienced while transitioning; “spaces designed to clean, conceal and correct” things socially considered “dirty, abnormal or other” – but also addresses the way transgender issues are generalised and “sterilized” through neat clinical terms. Artists in Kiss My Genders marry the intensely personal with the social, emotional with the playful, and at the same time evoke all the contrasting feelings of pride, comfort, fear, frustration, belonging and exclusion.

The exhibition succeeds in its “celebration” and “expression” of identities – but the presentation, at times, is confusing. The works of some artists are split across multiple floors, the labelling unclear, and it is generally worth asking the art assistants to talk you through the rooms – difficult, when the gallery is at its busiest and a shame for an exhibition set on “opening doors.” Perhaps this is all the more noticeable as the exhibition appears to be catered towards an audience that identifies with binary genders – many of the artworks require the context of the theme or artist in order to be appreciated. Often, however, this is used in a positive way; many of the exhibits are truly thought provoking.

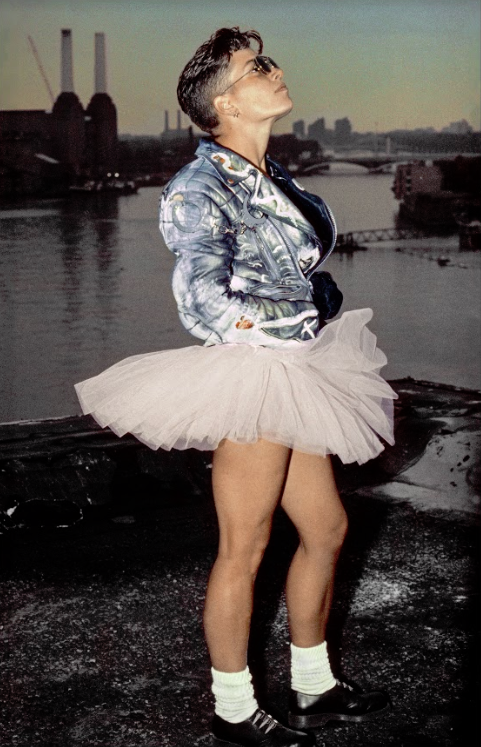

Most strikingly, Something for the Boys takes us through a spiral of ruched curtains in metallic pink – as if we are walking into a private adult show, yet at the same time, as if we were walking onto a stage. In the centre of the spiral we find ourselves in a circular womb-like room with a screen. Cutting between various LGBTQ+ spaces in Blackpool, the projected film shows an increasing disconnect between sound and image; a drag queen mouthing to “I am who I am” off-sync, interjected with a club-dance choreography, stills of gay clubs, the camera panning over pornographic videos and fetish-wear, and back to the drag queen – except this time she just mouths, and all we can hear is industrial sounds – once again connecting gender-identity and sexuality to cultural identity as a whole. But there is also something intimately performative about the display – the gesticulations and dances, unhinged from their appropriate music, seem to point to a theme of performance and spectatorship at large. And suddenly, that circular room no longer feels like a private theatre. It starts to feel like a stage, and the question crosses our minds – who is really the performer here, the drag act, or us, playing up to our female/male expectations? Just as Victoria Sin’s insistent murmurs, Kiss My Genders seduces its audience into truly looking – and becoming aware of the instability of their perspective in the process.